This is part of a series on ASEAN countries. There are few countries in the world that can boast such natural diversity and cultural richness as Indonesia. But this comes at a price, as ASEAN’s largest nation has been tested repeatedly by the follies of man and nature alike, all resulting in a determined resilience and undeniable strength in its people. The Expat’s editorial team looks to Malaysia’s neighbour, the magnificent and vast archipelago of Indonesia.

For lovers of statistics, there is much to marvel at in Indonesia but, sadly, much to sympathise with, too. This archipelago consists of some 17,500 islands, 34 provinces, and over 255 million people comprising hundreds of distinct ethnic groups, making it the world’s fourth most populous country, but one whose people live with the ever-present threat of earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, forest fires, floods, and landslides. It is not just human life that suffers the impact of these natural disasters, either, with hundreds of millions of dollars in economic damage unleashed every year on a country already seeing over 30 million of its inhabitants living below the poverty line.

And yet history tells of foreigners coming by the thousands, drawn by the allure of natural resources and a strategic position on the trade route, while more recent foreigners come for the beautiful islands, the food, the culture, and the welcoming hospitality of the Indonesian people. Straddling the border between Asia and Oceania – possessing elements of both, as well as boasting plenty of attributes unique to the archipelago – Indonesia is one of the world’s most intriguing countries.

Power struggles

For more than 1,000 years, money-seekers have dropped anchor in Indonesia, and the earliest records show key trade routes existing between the early empires of China, India, and many parts of Southeast Asia. In more modern times, the Europeans came calling, their tongues tantalised by the region’s spices, and the Portuguese were first to establish themselves in 1511, taking control of the whole trade network (including Indonesia) from their headquarters in Melaka before being booted out by the Dutch and their mighty Dutch East India Company.

The Dutch certainly made themselves at home, remaining in Indonesia for three and a half centuries and, in addition to the lucrative spice trade, also cultivating sugar and coffee for a growing world demand. During the heyday of this time, Indonesia was providing three-quarters of the world’s supply of coffee, and the economy was booming.

Eventually, however, the Indonesian people decided enough was enough. Thoughts of independence were stirring as World War II broke out, and the nationalist movement grew only stronger during the long war and Japanese occupation of the islands then known as the Dutch East Indies. On 14 August 1945, mere days after the Americans accepted Japan’s unconditional surrender, Indonesia declared itself an independent Republic, and nationalist leader Sukarno was placed in the presidential seat.

The Dutch tried to re-establish rule in their prized colonial territory, but the Americans were not amused. US funds which had been earmarked for Dutch Indonesia were immediately cancelled and the Americans further moved to cease all post-WWII aid to the Netherlands in an effort to pressure the Dutch into giving up their claim on Indonesia.

Still, the Dutch were intent on trying to re-establish their valuable Dutch East Indies holdings. The Indonesians, however, were having none of it this time. A bitter four-year struggle that saw both political upheaval and armed conflict erupted, effectively constituting Indonesia’s War for Independence.

Many tens of thousands were killed, mostly Indonesian soldiers and citizens, and millions were displaced on Java and Sumatra islands. Finally, however, in the face of steadfast Indonesian tenacity and withering international criticism, the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesia’s independence as a sovereign nation in December 1949.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sukarno used this victory to strengthen his own hold on power. Espousing strident anti-imperialist views against Western powers, and even a degree of antipathy towards his Asian neighbours – including Malaysia – Sukarno moved Indonesia increasingly towards authoritarianism during his tenure. Sukarno managed to maintain equilibrium in the vast archipelagic country for over two decades by precariously balancing the opposed forces of the military and the PKI, Indonesia’s Communist Party, even holding off an attempted coup in 1965.

Following the failed coup, for which the PKI was blamed, the Indonesian army led a violent anti-Communist purge, similar to other such actions throughout the region during the time. Widespread killings were enacted, targeting suspected Communists, ethnic

Chinese, and alleged anti-government leftists. Through this campaign, the PKI was

effectively destroyed, and hundreds of thousands were killed, perhaps many more.

But power was not to be held by Sukarno for much longer. Politically weakened and facing a strong military no longer loyal to his rule, he was ultimately removed from his seat by the army, headed by General Suharto, in 1967. In March of the following year, Suharto was formally appointed president.

The General’s subsequent 30-year reign divided opinion – his policies brought a degree of economic stability and established the country with some kudos with the West, but he was accused of grand corruption and condemned for the oppressive regime he operated. Suharto’s exit came soon after Indonesia suffered a devastating blow in the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, which saw the rupiah losing 80% of its value against the US dollar and leaving the country – once wealthy thanks to its oil reserves – in dire financial straits. No ASEAN country was hit harder by the financial turmoil than Indonesia. In May 1998, as public opinion swelled against him, he was forced to resign.

In this bleak atmosphere, with Suharto out of the presidency in disgrace and the national currency in freefall, East Timor piled on and declared its secession from Indonesia, following a quarter century of widely condemned military occupation aimed at suppressing the East Timorese people. Despite the dismal backdrop, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, Indonesia finally held its first democratic elections and, in 1999, welcomed in the first publicly voted leader in its history, Abdurraham Wahid.

The awesome power of nature

While man may have had plenty of say in Indonesia’s fortunes, Mother Nature’s whims have been just as impactful, and Indonesia seems to suffer continually for its geographical positioning. Between the Northern tip of Sumatra and the Lesser Islands, the Indo-Australia and Eurasia tectonic plates meet, with the former forced beneath the latter, creating a network of fault lines that serve up natural disasters both large and small, as and when they so desire.

Indonesia’s geography has been shaped by this tenuous plate placement, and many mountains and hundreds of volcanoes can credit the fault lines for their birth. Indeed, more than 120 of Indonesia’s 400 volcanoes are still active, and some are legendary. Few eruptions have been more devastating than the mighty explosions of Tambora in 1815 and Krakatoa in 1883, two of the most powerful eruptions in recorded history.

Tambora’s incredible eruption on the island of Sumbawa (just east of Lombok) began on April 5, 1815 and reached its explosive climax five days later, ultimately causing a death toll of at least 71,000 and going into the record books as the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history. It’s truly difficult to grasp the enormity of Tambora’s eruption: Some 100 cubic kilometres of rock were blasted into the air by the successive explosions, including roughly 41 cubic kilometres of volcanic rock ejected from within the earth. An enormous collapsed caldera was formed as a result of the eruption, and Mount Tambora’s elevation was reduced dramatically from its once-soaring 4,300m.

The explosions blew off the top third of the mountain, reducing its height to just 2,851m. (Today, it’s further dropped to 2,722m.) The massive eruption was 61,500 times more powerful than the Hiroshima atomic bomb blast and released 158 cubic kilometres of volcanic ash, enough to bury the whole of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore in well over a metre of ash. The colossal eruption column was so vast, in fact, much of Southeast Asia was plunged into darkness for a week. As the ash column rose into the atmosphere and spread around the world, global temperatures were significantly lowered, and the following year was known in the Northern Hemisphere as the Year Without a Summer. Crops failed worldwide and famine was widespread.

Almost 70 years later, on a small island between Sumatra and the western tip of Java, Krakatoa rumbled to life. For a period of two days in late August 1883, this volcano erupted with a series of cataclysmic explosions that obliterated two-thirds of Krakatoa island and the surrounding archipelago, destroyed over 160 nearby towns and villages, caused incredible tsunamis up to 40m high, and killed at least 36,000 people. The explosive blast – said to be the loudest in human history – was heard as far away as Turkey. The pressure wave from the final explosion circled the globe three and a half times and ruptured the eardrums of sailors who were 65km from the volcano at the time. With some 20 million tons of sulphur propelled high into Earth’s atmosphere by the eruption, around 70% of the planet experienced atmospheric colour displays and vivid sunsets and sunrises for years following the eruption.

Unleashing the full might of the Earth’s formidable power, Krakatoa remains perhaps the most violent and destructive volcanic event in recorded history. The disasters that have been rolling over Indonesia in more recent times are not quite as explosive as the 1883 Krakatoa eruption, but they have been nonetheless horrendous for the many people affected. The devastating December 2004 tsunami that ravaged many of the region’s coastlines and claimed hundreds of thousands of lives was triggered by a massive undersea earthquake off the north coast of Sumatra, while the May 2006 earthquake in Yogyakarta was responsible for some 5,700 deaths. Yogyakarta is also in the shadow of Mount Merapi, which is Indonesia’s most active volcano, with over 80 eruptions since 1000 CE.

Mount Kelud in East Java is another active volcano, with its most recent major eruption occurring in February 2014. And these are only the large earthquakes and notable volcanoes: There is no shortage of seismic activity in the country and, on nearly any given day, Indonesians wonder when the next quake will jostle the foundations of their land or a nearby volcano will awaken from its slumber, as if to remind them that their lives are never completely secure.

Staying strong

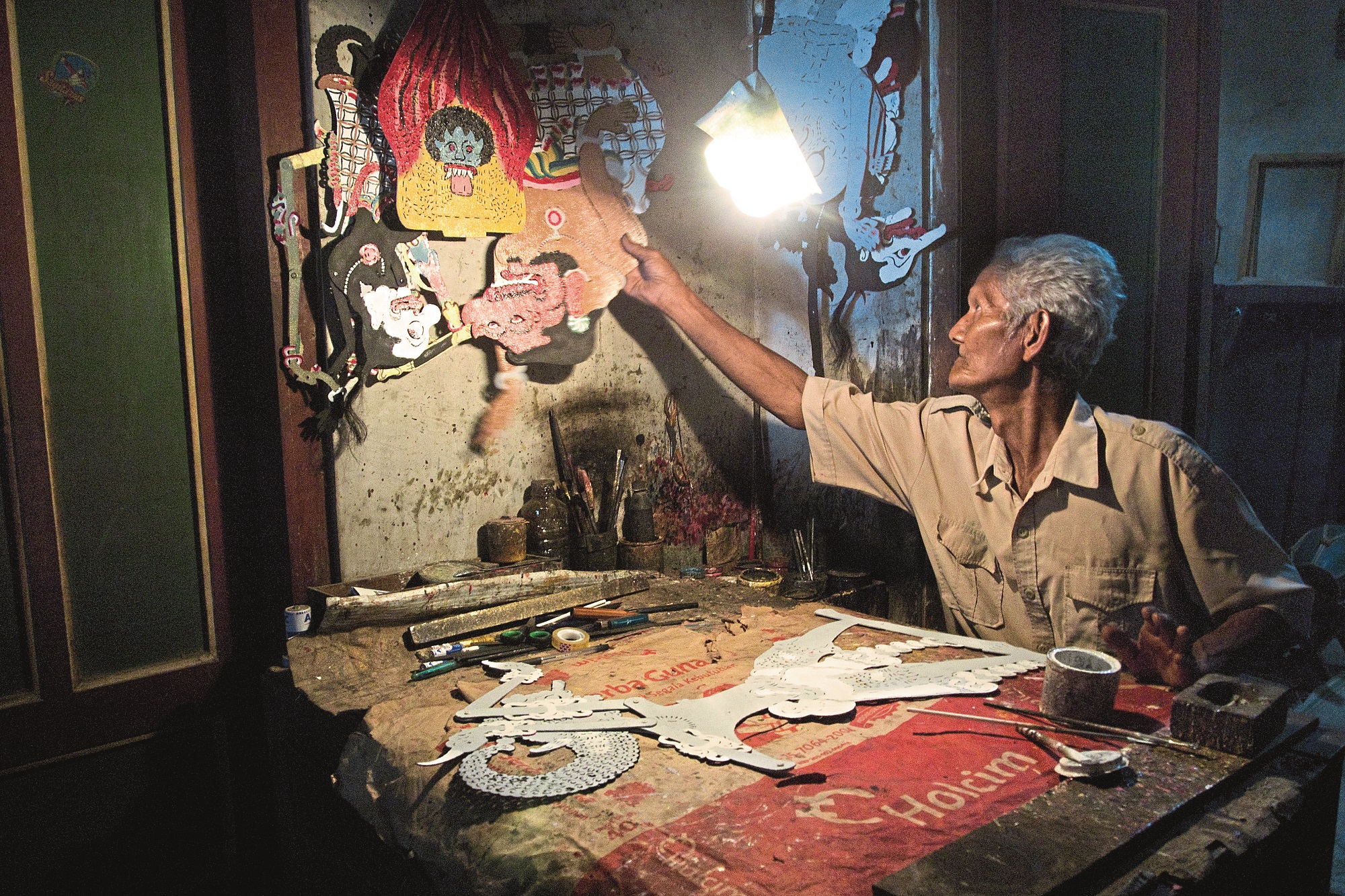

Despite being pushed and pulled by man and nature in equal measure, the cultural heart of Indonesia beats strongly, and there are few nations in the world that can boast such diversity and variety – both in its natural wonders and in its human population – as Indonesia.

The diversity of Indonesia’s people is quite extraordinary, and while the Javanese make up a plurality of the population, there are more than 700 dialects and languages spoken across the hundreds of ethnic groups, as well as widely varying rituals and beliefs practised: the Javanese have layers of formality built into their language, while the Minangkabu of Sumatra still stick to their ancient matrilineal society, with daughters inheriting the family wealth.

It seems only appropriate that the nation’s motto is Bhinneka Tunggal Ika – “Unity in Diversity” – and it is little wonder that Indonesia is so beloved by so many people, not least the proud citizens who are quick to spout effusively on the natural splendours (and there are more than you can count), the cultural intrigues, the food, the climate, and, of course, their fellow Indonesians.

Indonesia fact file

- Size: 1,904,569 km2 (World rank: 15th)

- Population: 255.5 million (2015 estimate)

- Capital city: Jakarta

- Largest city: Jakarta

- Government: Unitary presidential constitutional republic

- Official language: Indonesian

- GDP PPP*: $11,633

- HDI**: 0.684, medium (World rank: 110th)

- Currency: Indonesian rupiah (1MYR = 3,230IDR)

*GDP per capita, purchasing power parity, international dollars

**Human Development Index, a comparative measure of life expectancy literacy, education, standards of living, and quality of life for 188 countries worldwide. (For comparison, Malaysia’s HDI is 0.779, high, and is ranked 62nd.)

Notable facts:

- A vast archipelago comprising over 17,500 islands, Indonesia is home – in whole or in part – to half of the world’s six largest islands (New Guinea, Borneo, Sumatra) and the world’s most populous island, Java, with 133 million inhabitants.

- The archipelago of Indonesia, straddling the equator, separating two oceans, and possessing over 80,000km of coastline and vast tracts of rainforest, supports the second-highest level of biodiversity on Earth. Nearly 40% of the mammals and 36% of the bird on these islands are endemic to Indonesia.

- Indonesia has over 150 active volcanoes, including Krakatoa, Tambora, Merapi, Agung, Kelud, and Rinjani. Some of the most devastating eruptions in human history have occurred in this region, including the Lake Toba supervolcano eruption in Sumatra some 75,000 years ago, one of the largest known eruptions in Earth’s history.

- Over 300 distinct ethnic groups are spread across Indonesia’s many islands, with the Javanese, at 42% of the nation’s population, representing by far the largest and most politically influential group.

- The island of Java, which is roughly the same size as Peninsular Malaysia, is the world’s most populous island and holds over half of Indonesia’s entire population, a staggering 145 million people. The island is almost completely of volcanic origin and today is home to 45 volcanoes which are considered active.

This article was originally published in The Expat magazine (October 2016) which is available online or in print via a free subscription.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "