Amid so many new buildings springing up in Malaysia, the landmark Diamond Building in Putrajaya may not be brand-new anymore, but it still delivers a masterclass example of how the thoughtful application of green building techniques can dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of a structure. Editor Chad Merchant marvels at the finished product and discovers how this particular diamond may just be the planet’s best friend.

It’s not the tallest building in Malaysia by a long shot. It’s not the largest. It’s not the most expensive. And, given the breakneck pace of construction in the country, it’s not even close to being the newest. But the headquarters of the Malaysia Energy Commission, a stunning seven-storey wonder colloquially called the Diamond Building, can easily lay claim to the being the country’s most energy-efficient building.

In fact, given that the Diamond Building took the top award at the ASEAN Energy Awards back in 2012, it might be more fitting to conclude this is among the most energy-efficient buildings in the entire region.

From the ground up

So what’s involved in designing and constructing a building that uses only one-third the energy of a normal office building of similar size? The man with the answers is energy engineer Gregers Reimann, one of the principal players in the building’s creation, and the managing director of IEN Consultants in Bangsar, a green-building consultancy that was contracted as the sustainability consultant on the Diamond Building. Over six years since work began on this game-changing building, Reimann is still there with IEN, and still remembers the Diamond Building’s design and construction with fondness.

“Being involved from the design phase all the way through construction made a real difference,” Reimann explained. “It’s much more comprehensive than just designing a building that uses less electricity. We looked at everything. Nearly all the resources utilised in the facility are fashioned from sustainable and energy-saving materials.”

He went on, “Some of this is fairly obvious, like solar panels, energy-saving light bulbs, and more efficient computers and office equipment, but much of it is unseen.”

Innovative ideas

Reimann explains some of the amazing features of the Diamond Building, which quietly make the structure so efficient: A rainwater harvesting system for such needs as toilet-flushing, which, together with water-saving fixtures, cuts the building’s water usage by 70 to 80%. A literal “green roof” that sees nearly 20% of its surface area planted with grass turf to mitigate the building’s heat island effect.

An ingenious window and precisely angled louvre system which allows daylight to be efficiently captured, reflected, and diffused to provide roughly 50% of the building’s lighting, while the self-shading angle of the exterior window façade blocks mid-day direct solar impact. The spectrally selective and low-e glass further ensures that capturing that daylight doesn’t carry with it the typical liability of capturing the heat as well, thus reducing reliance on air conditioning.

Further contributing to a comfortable environment, the floor conceals a network of pipes carrying chilled water, which operate during the night, cooling the concrete floor which acts as a thermal storage medium.

During the working day, the concrete slab passively releases the stored cooling effect into the indoor environment by radiant cooling and thermal convection, reducing the peak heat load of the building, and further reducing the reliance on air conditioning. In fact, the chilled slab system is a key component of the building’s thermal comfort design.

Another major point of efficiency is the building’s lighting. A full 50% of the interior lighting is supplied by natural daylight, and a comprehensive lighting approach, including light sensors which switch off common-area lights when the ambient lighting is sufficiently bright, and motion-activated lights in areas such as washrooms, help reduce the building’s total lighting energy consumption by a remarkable 74%.

Care and consideration

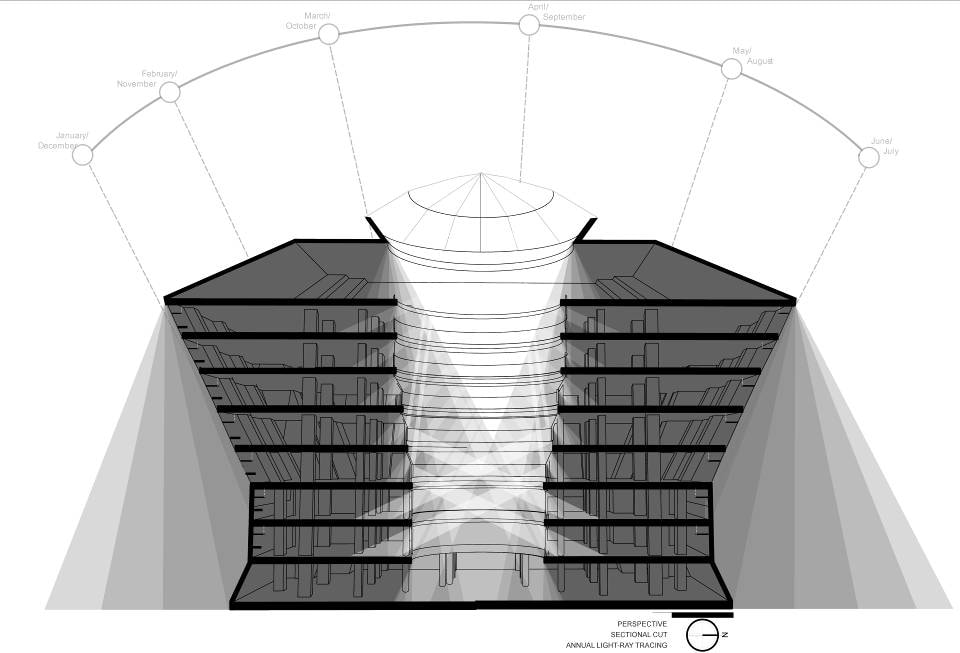

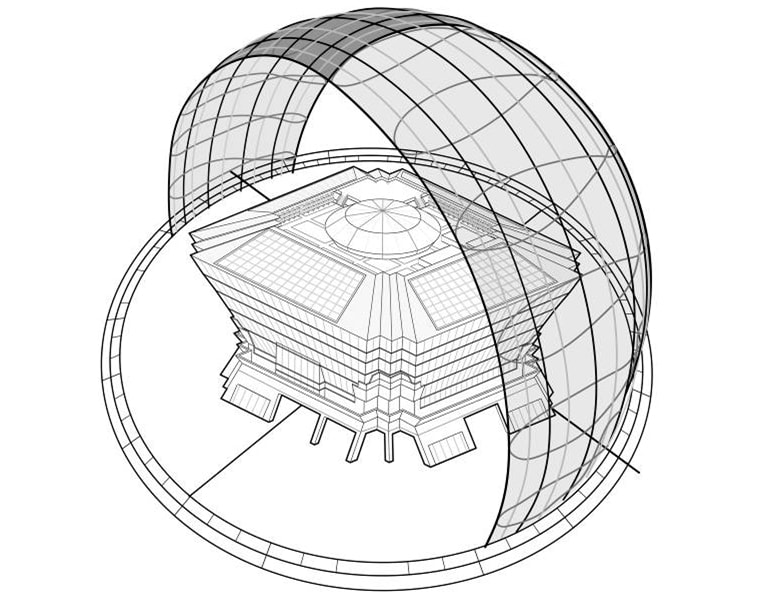

Even the orientation of the building was carefully decided before the foundation was poured. IEN Consultants devised a “solar profile” of the building, and by using a chart of the sun’s daytime path over the building’s site, determined the exact orientation of the building for maximum solar efficiency, both in terms of reducing the heat load and exploiting the stored energy of the sun’s rays. To that end, over 830 square metres of photovoltaic panels were fitted to the roof, harnessing the power of the tropical sun and covering 10% of the building’s entire energy consumption needs.

But at what cost does all this energy efficiency come? Reimann speaks of a general rule of thumb he finds to be true: “We find that, on average, a green building costs five percent more to construct than a standard building. However, that additional expenditure results in a 50% saving in energy costs, so the initial investment can easily be recouped in the first five years of the building’s operation. After that break-even point, all of the energy savings go directly to the bottom line.” And these savings are not insubstantial: in the case of the Diamond Building, which actually exceeds that average 50% savings figure by a good margin, the real-world cost savings hit about RM1 million per year.

Putting Malaysia on the map

All of this, and so much more, has resulted in a host of awards and recognition for the RM72 million Diamond Building. It was the first building in Malaysia to obtain this country’s Green Building Index platinum rating, the highest level on the index. It was the first building outside Singapore to earn that country’s Green Mark platinum rating, also the highest rating available. And now, the Diamond Building has been named ASEAN’s most energy-efficient building, an award that Reimann equates with a movie winning a Best Picture Academy Award. “It really is a top honour,” he explained. “The ASEAN Energy Awards began in 2000, and are held each year to recognise the highest levels of excellence and creativity in the field of energy efficiency.”

As Malaysia continues its long-term goal of becoming a fully developed, high-income nation by 2020, pairing achievements in that quest with the desire to be environmentally responsible is something Reimann sees as a real opportunity for the country, an area in which Malaysia can stand out as a leader in Asia. “My dream?” he smiled. “I’d love to see Malaysia do even more. It would be amazing if the country could make carbon-neutral buildings mandatory by 2020. What a statement – and step in the right direction – that would be.”

By taking an appreciative look at not only the stunning façade of Putrajaya’s energy-stingy Diamond Building, but at what lies inside, too, it’s easy to envision a future city where such green buildings are the rule rather than the exception, and cities full of such diamonds would indeed be Planet Earth’s best friend.

This article was originally published in Senses of Malaysia, which is available online or in print.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "