This post was written by Samantha Ho and was originally published on edGY.my

Photo credit: naimfadil / Foter / CC BY-SA

By now, we know that Malaysia’s real estate market is unaffordable for most middle to lower income folks. But new research by think tank Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) shows in great detail exactly how scary the situation is.

KRI’s report Making Housing Affordable details how the urban centres of Malaysia are facing an affordable housing crunch. KRI sets out the problems that Malaysia is facing. “Gaps are beginning to appear in the system, as exemplified by the growing concern of middle-income households who are neither eligible for social housing nor are able to afford private sector-supplied houses.”

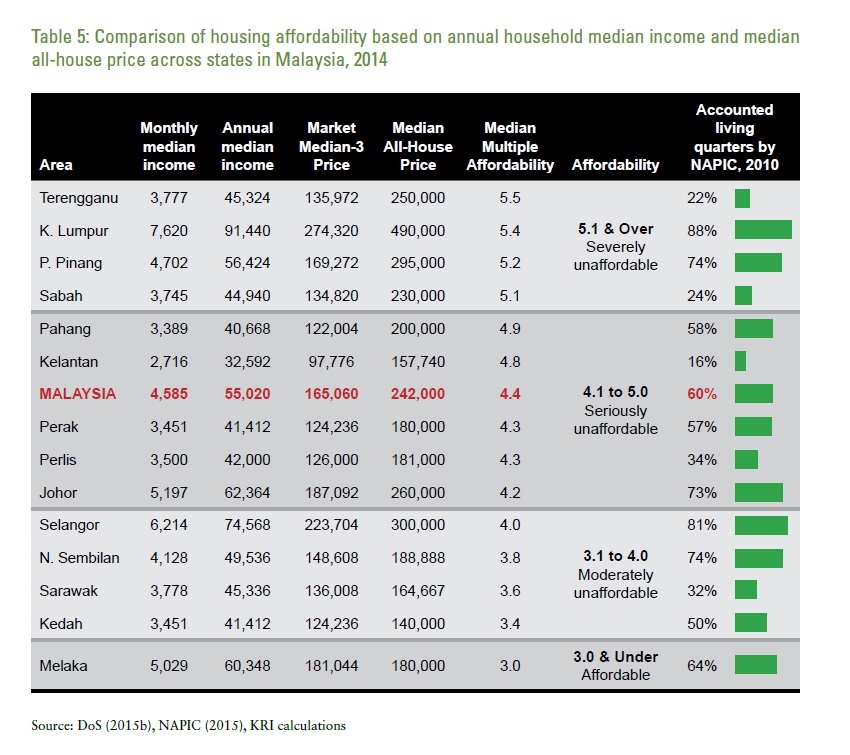

At a national level, KRI’s report said that Malaysia has a “seriously unaffordable” housing market. Using median multiples as one of the two methods to assess the situation, KRI noted that median house prices are 4.4 times the median annual household income in 2014. By global standards, an “affordable” market should only have a median multiple of 3.0 times.

In Malaysia, only one state, Melaka, has been classified as having an “affordable” housing market at 3.0 times mean multiple.

There are four states that have “severely unaffordable” markets are Terengganu, Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Sabah.

Unaffordable housing markets are those which have supplies that either falls far below demand or are too inelastic to changes in demand. It is a measure of how affordable the housing market is as a whole, not a measure of what any particular household can afford as that would depend on that household’s circumstances, KRI’s report noted.

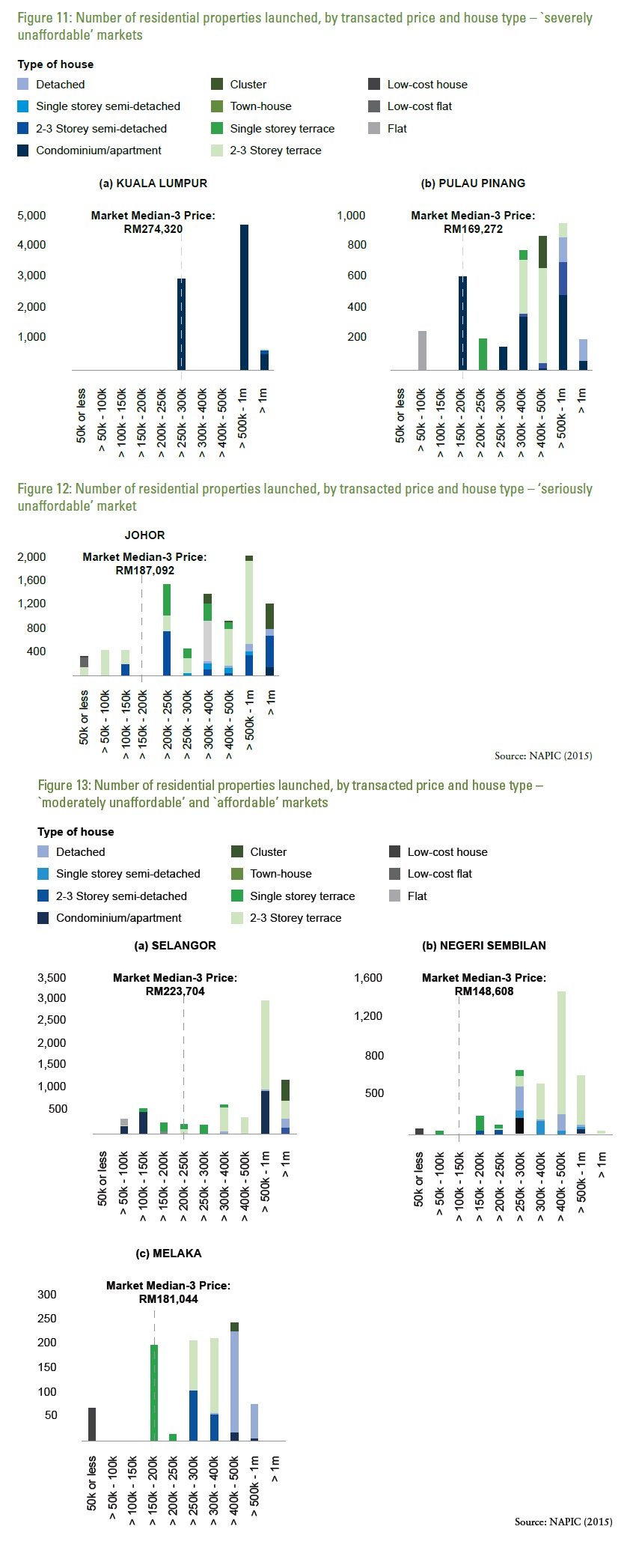

A deeper look at Kuala Lumpur and Penang’s property market shows that there simply isn’t enough affordable housing being built or as KRI’s report puts it, the supply is simply unresponsive to effective demand.

For example, in 2014, there were no properties launched in Kuala Lumpur that were below the RM250,000 to RM1 million price bracket. Most of the newly-launched properties were in the RM500,000 to RM1 million bracket.

How much would an “affordable” house price be in Kuala Lumpur, if we go by three times median multiple price? In 2014, it would be RM274,320, KRI said.

In Penang, the situation is slightly different. There were some houses in the RM50,000 to RM100,000 price range. But remember, the median household income in Penang is slightly lower than that of Kuala Lumpur. Penang’s property market is still deemed “severely unaffordable” because there was a lack of houses launched at below three times median multiple price as well as a large number of high-end property launches.

So, why is housing so unaffordable in the first place?

Housing supply is driven by land costs and use, planning policy and construction costs. High housing prices are often blamed on land costs but KRI has found that actually, it is rising house prices that result in rising land prices.

At a presentation today, KRI director of research Dr Suraya Ismail pointed out: “All regions experienced a reduction in building costs in the period 2011 to 2012… then we should have expected a reduction in house prices to have occurred in 2013 or 2014. However this was not the case”.

So how can Malaysia make housing more affordable? KRI reckons the answer lies in making the supply of housing more responsive to the needs of all sections of the population.

“If we want a responsive supply sector, they must follow the distribution of household income,” Dr Suraya said.

According to the report, new launches of houses in the lower price range were also found to have dropped from 36.4% in 2004 to only 19.7% in 2014. The average value of residential properties have been increasing every year from RM248,514 in 2012 to RM292,661 in 2013 and RM331,888 in 2014.

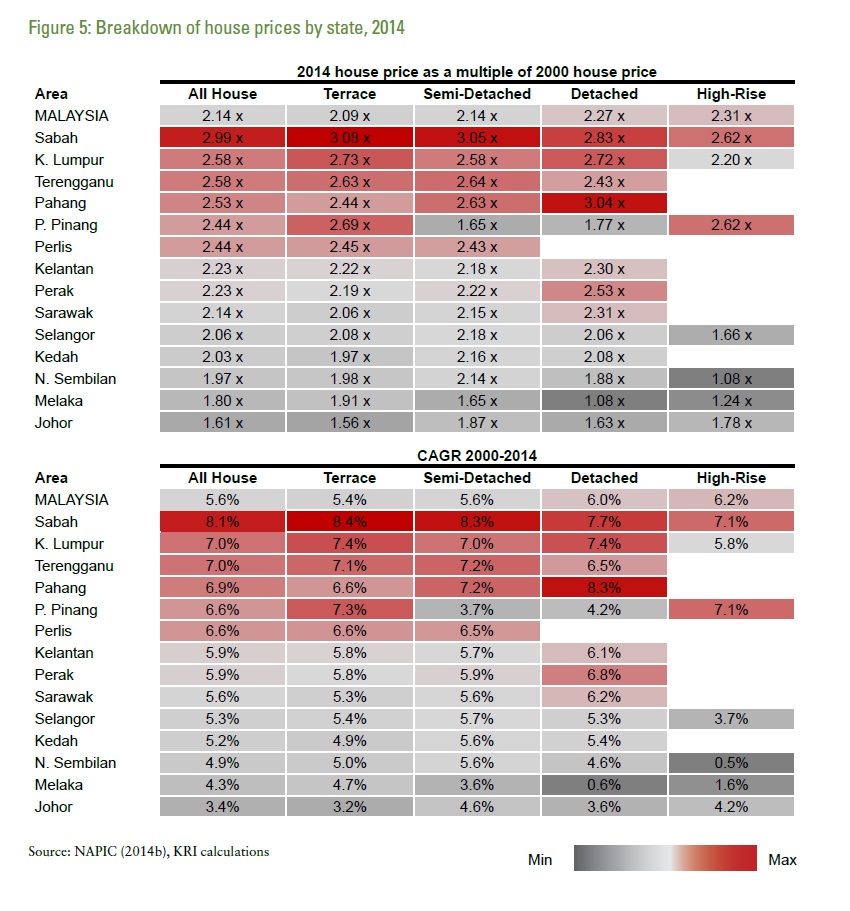

Here’s how much house prices have gone up since 2000 (2014 house prices expressed as a multiple of prices in 2000).

Then, there are demographic factors that make the problem more acute. Malaysia’s population is projected to hit 38.6 million by 2040, at a growth rate of about 2% a year.

There will be more households in the future, but with fewer members, meaning more houses will be needed in the future.

Recommended solutions

KRI’s recommendations focused largely on institutional improvements in the private sector, namely integrating design and construction processes so that the production of housing products would become more efficient.

This was seen as capable of making supply more elastic so that when demand for houses surges, their prices would not surge as much.

“If people want to build houses for rich investors from overseas or Malaysians, that’s fine,” said Datuk Charon Mokhzani, managing director of KRI. “What we’re saying is that we also need to have an affordable housing market. We have to be producing houses which are affordable for 80% of the population.”

However, developers are mistaken if they assume affordable housing projects are less profitable. Khazanah’s case study of 8990 Holdings in the Philippines showed that their affordable housing project profited the developers via mass production and the use of pre-cast construction, which enabled them to complete the homes within a fortnight.

These homes were priced at only PHP715,000 (approximately RM57,200) complete with two bedrooms and swimming pools, and the company even offered a financing scheme for consumers who did not have enough savings for the down-payment, but could afford monthly instalments.

Another question raised was whether existing government schemes such as PR1MA were effective in making housing more affordable.

According to Charon, KRI envisions a move away from using such “traditional proprietary systems” such as PR1MA towards shorter moratoriums as the market self-adjusts to prevent speculation on affordable homes.

PR1MA homes are currently subject to a ten-year moratorium during which the property cannot be sold or bought without prior approval, in order to prevent prices from rising due to speculation.

Ultimately though, Khazanah’s report aims to make the issue of affordable housing less of a social welfare concern, especially one that is dependent on the government for subsidies.

“We can’t keep subsidising 80% of the population…it doesn’t work,” Charon said.

Instead, what the government can do is to encourage more productive and efficient construction of homes, such as facilitating the adoption of the Industrialised Building System (IBS) and expedite the National Housing Survey as proposed in the 11th Malaysia Plan, Dr Suraya said.

“You need to have a proper database in order to plan for how many housing units [we should have],” she added, saying that this could even be made into an open data source for the public to analyse.

Read the KRI’s full report on affordable housing here.

Read This: 5 Things You Must Do When Shopping For a House

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "

Very very expansive….

Reifelizs Rei

great article!

This what happen when the free market flow without control…suddenly it’s too late and too hard to control. The middle class suffer.