On the frontline: ExpatGo talks to Kim Gooi, Malaysia’s veteran war journalist

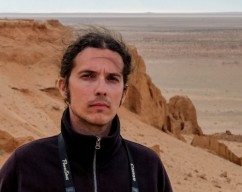

Kim Gooi is probably Malaysia’s least celebrated photojournalist, so Marco Ferrarase set out to learn more about the enigmatic man. Pictures by Marco Ferrarese and Kim Gooi.

Very few indeed know about this bohemian Asia old hand, the only Malaysian reporter on the Cambodian frontline. He worked for major TV networks in the US, UK, Australia, Europe, Japan, Hong Kong, and was the stringer for Times Magazine and New York Times.

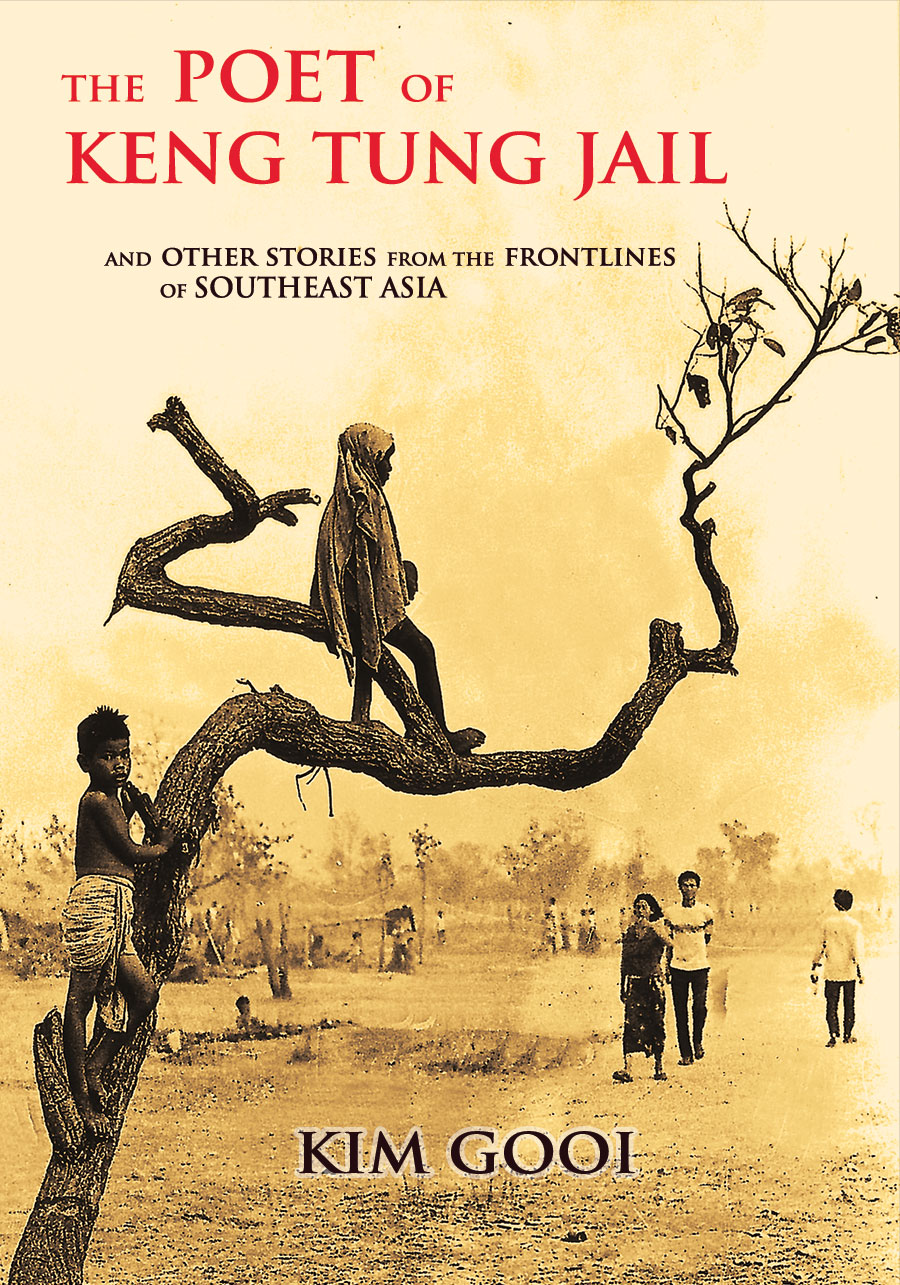

In 1977, he was sentenced to six months imprisonment in the Keng Tung jail of Burma for illegal border trespassing and was only released a year later thanks to the intervention of the Malaysian embassy in Rangoon. Among other key characters of Southeast Asia’s modern history, he met Shan warlord Khun Sa, Myanmar’s infamous ‘Opium King’.

It’s all captured in his book, The Poet of Keng Tung Jail – a collection of essays on life in prison, maintaining health through mastering the art of tea, and episodes from the frontlines and most hidden corners of Southeast Asia. Kim Gooi writes with great vibrancy, wit and an uncommon deal of honesty.

One particular scene from the book shows his indomitable character: while incarcerated, Gooi meets Aktar, a powerful and rich Muslim leader who bribed the prison guards to improve the quality of prison life from the existing hell, by providing home-cooked food and reading materials daily.

Aktar invites Gooi to join his group and gives him a copy of The Life History of Prophet Mohammad to read. He hopes that, when he is released, Gooi will help tell Malaysia’s Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman to stop the killing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma.

Aktar invites Gooi to join his group and gives him a copy of The Life History of Prophet Mohammad to read. He hopes that, when he is released, Gooi will help tell Malaysia’s Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman to stop the killing of Rohingya Muslims in Burma.

A couple of weeks later, Aktar asks Gooi what he learned about Islam from the book. The answer satisfies the leader: Islam is the most egalitarian and socialist of religions, one that emphasises solidarity. But Kim Gooi is not finished.

He questions Aktar by asking why, then, many women in Islamic nations are treated as inferior. He believes they should instead be considered as the base of Islam, because it was wife Khatijah who coaxed the Prophet to return to the mountain and receive the word of God.

Aktar can’t tolerate such an irreverent question, and shouts. But he will never deter his bold, sharp-tongued Malaysian friend.

Kim Gooi discovered the world of journalism at 21 years old when he met a Dutch freelance photojournalist travelling on a train in Northern Thailand. He started selling his first stories when studying in Singapore, and a couple of years later moved to Bangkok to chase his dreams. “When I arrived in the 1970s, Bangkok had opportunities, great food, no traffic jams and way too many available women,” he says.

“The US base in Northeast Thailand had just closed down, and many officials had come to live in Bangkok”. That’s how Kim started to make a quirky living: “My first job was letter writer: as I was learning to speak Thai, I helped bar girls read and write letters in English to their ‘johns’. At first, they paid me in beer, but when it became too much booze, I started asking for money.”

Kim moved to the Thai-Cambodian border. “My arrival was perfectly timed with the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge shuttled to the Thai border to recruit people and fight against the Vietnamese,” he remembers. “There were thousands of refugees dying at the border.

“US$200,000 was the standard for a 30-minute documentary”

The BBC, CNN, and other Japanese TV stations needed feature stories and documentaries and had big budgets. US$200,000 was the standard for producing a 30-minute feature documentary, and everyone wanted to show off, competing with each other to deliver the best coverage,” Kim fondly remembers.

“I was the top gun in Aranyaprathet; people like Italian foreign correspondent Tiziano Terzani came only years later. Also, they didn’t speak Thai and depended on interpreters. I was a one-man crew: I started working with TV productions, making as much as US$150-200 a day, quite a fortune back then, and all because of a terrible war”.

In the early 2000s Kim returned to Penang, where he currently lives. He was one of the first Malaysiakini writers, but gradually abandoned the profession to dedicate himself to his other passions: tai chi and the blues harp. Part of his choice was because of disillusionment with the way journalism had changed since his Bangkok heydays.

“Today, editors ask for only about 500-800 words. It’s too short to expose good researched facts: when you read an article now, you realise that the author has probably talked to a person for only a couple of hours, and has written the feature right after. Back then, we sacrificed up to a week per story. Also, journalists today don’t read enough background information and don’t study the culture of the places they cover too well.”

“The process of writing magazine features has changed a lot”

Kim maintains his critical views on Penang. I ask him about George Town’s transformation to UNESCO World Heritage Site. He’s skeptical. “I grew up here, and my understanding of the heritage is real. I think that what they have done today is a disaster. The UNESCO listing was awarded to a ‘living city’.

“That means Chinese, Indian Muslims and Malays, all living together in harmony. It’s not the cookie-cutter boutique hotels and expensive cafés that chased out the original inhabitants and craftsmen from the streets… Our ancestors are turning in their graves.”

More of his tales of wonder and woe, and extracts from The Poet of Keng Tung Jail, can be read at his blog, where you can contact Kim Gooi or order copies of his book.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "