Franck Ducharne is the CEO of Entofood, a company committed to sustainably producing protein for animal feed and organic fertilizer for plant nutrition through using insects to digest organic waste. We caught up with Franck to discuss the concept and how, realistically, it could save the world.

The search for sustainabilty

Tell us about your background.

Originally I’m from the world of biology – invertebrates and aquaculture, or zootechnics. I studied in in France, specialising in sericulture (farming silkworms) in both France and Brazil. From there, I moved to Central America and started a long career in aquaculture, shrimp farming in particular. I went in Guatemala, Madagascar, Thailand and traveled the world for almost 17 years.

When I finished my ‘world tour’, I spoke to an entrepreneur friend I met in Madagascar (I lived there for 13 years). He was studying opportunities for a sustainable way of producing protein using insects. That friend, Frederik, would become my partner.

So how the launch of Entofood come about?

In 2010, we went back to Madagascar to study insects which would match our objectives – insects which could [digest organic waste] to leave a protein product and ideally, a product not commonly used by human or directly by livestock.

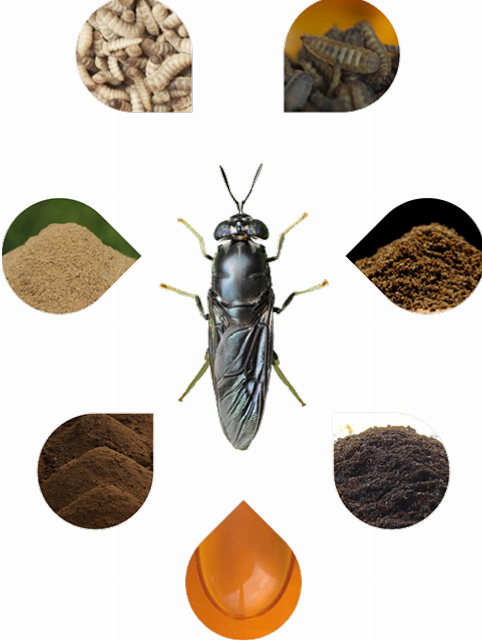

Little by little we narrowed down the choice – to the black soldier fly. We collected some from the environment and we started the duplication program. We learned how to breed them, how to produce eggs, how to hatch them, how to grow them, how to transform them into meal, and how to process the byproducts.

Waste, wasted

Where does the fuel [organic waste] for your project come from?

We are in fact sited on a huge resource of waste; it’s everywhere, in fact… the planet generates it. It can be rotten apples, it can be lettuce which is left in the bottom of your fridge, the leftovers from restaurants, from catering, schools, industry… In 2013 there was a UN report that estimated that the total volume of food wasted along the whole supply chain from the farmer to the end consumer is about 30% of the world’s food produce.

Now it’s a matter of trying to get access to it. Eventually, in Europe it ends in a composting unit or in incineration, but in developing countries, it ends up mostly in landfills. Every country has its way of dealing with waste, but basically you still have huge amounts of nutrients which are not utilised at all. It’s waste, wasted.

In the natural life cycle of nutrients, when for example, you take a piece of orange to a picnic and leave it on the floor, you have animals coming to eat it, digest it and poo it and this will make fertilizer for the grass.

That’s the natural cycle; a group of animals called detritivores – including bacteria, fungus, microbes, and invertebrates – do the job. This soldier fly is one of them, and now we are breeding them to produce a natural recycling system in a controlled environment.

Why is this process better than well-established composting techniques?

I think probably there’s only investment in composting because of CSR [corporate social responsibility] reasons; a company says “we send X% to compost instead of landfills” and they maybe get subsidies or grants because of it.

But the requirement of space and time is enormous. For us, 50 tonnes of waste per day, which would represent a plant, will be sized at around 5,000 square metres. The process of transformation of the waste doesn’t take months, it’s completed in one week. So it’s extremely powerful and efficient.

Where’s the rubbish?

Why did you set up in Malaysia?

After a year and a half of research and narrowing our business model, we couldn’t stay in Madagascar as there was no market, especially with the political situation. So we decided to move to Asia where there’s an economic boom, a growing population [the driving factor behind the projected 9 billion global population in 2050], and where 88% of the world’s aquaculture (fish farming) is done.

There’s also a rapidly growing middle class; people are spending and consuming more, creating more demand on the food supply. People at one time only ate rice. Now they want chicken, shrimp, tenderloin. The forecast of demand of meat in general for the next decade is going to double.

Experience suggests, too, that the richer you become, unfortunately, the more wasteful you become. When you are living in the countryside, you are not generating much waste. You eat or save every piece of food available and you give the rest to your chicken or pig. In cities, we enjoy convenient, processed foods – and processing generates waste.

Changing the status quo

What is the industry like at the moment?

This technology and the purpose behind it is to change our mode of protein production. With current sources like soybean (200 million tonnes a year), you have five countries around the planet producing 90% of the soybean. The whole planet relies on them so you have a huge commodity market.

We want to try to bring the protein production closer to the user, and the beauty of this animal is that it’s present everywhere. The process simply recreates Mother Nature but more efficiently, turning waster into fertiliser and biomass.

Cities like Vancouver are already moving towards banning landfill for organic waste and the COP21 event is encouraging this development of a circular economic system.

This means reducing import / export transport and carbon footprints, and try to develop as much as possible a circular economy [where waste is returned to protein] and create a zero-waste system.

The insect biomass is transformed into protein for feed and their faeces can be used as organic fertiliser; nothing is wasted.

This is a wonderful idea but how do you get people to change their behaviour?

The first step for us is to have a first plant up and running – something big where you see trucks of organic waste going in, and coming out – nothing except protein and fertiliser. Wow!

Aquaculture: an industry in trouble

Why are you creating protein for fish and not any other creature?

The demand for food protein for aquaculture is growing like crazy; there’s a big effort to develop a sustainable solution to make this protein. Aquaculture is using a lot of ‘fishmeal’ because most of the fish people like to eat, such as tuna and salmon, are oddly carnivorous.

Recently, for the first time in human history, it was I think 2015 or 2014, the level of farmed fish and seafood eaten by humans reached the same level as fish caught at sea. In the early days of salmon farming, the feed was maybe 50-60% fishmeal. Today, 20 years later, it’s around 20%. And they are eating soybean like crazy because the prices have been increasing drastically for fish meal.

Production hasn’t increased so you have to find solutions. We think insect meal works as a substitute for fishmeal because it’s still animal byproduct and has a good nutritional factor. In fact, it’s a beautiful product – it’s quite tasty!

So why not directly create food for humans?

Of course, it’s not very fashionable; it’s not easy to sell ‘eating digested waste’ as a concept. People feel uncomfortable knowing that the creature has eaten waste. In Europe, regulations are very strict – especially since the BSE [Bovine spongiform encephalopathy or Mad cow disease] outbreak in the 1990s. The good thing about this technology is that the insects can be fed on something which is highly traceable and bred in a controlled environment.

Direct human consumption is not our goal, but maybe in places like Southeast Asia, where the insect-eating culture is so developed it may be possible. Even in Europe, Belgium recently revealed a list of 10 insects authorised for human consumption. It still a very niche market, but people are getting more aware and accepting of it. It’s not fashionable at the moment, but we’re running out of time to be fashionable.

Again, we not playing with nature, we are just speeding it up.

Expansion and development

What are you goals with Entofood for 2017?

Now we are in the fundraising process for our first plant in Malaysia and at the same time we are starting the roll-out in other countries through technology transfer. The first plant should start operation by the end of this year and will initially process at least 50 tonnes of organic byproduct daily.

This unit will be a first in SE Asia and could be a model to roll out into any state, any country. We’re looking for partners and trying to raise the profile of the company – not only here in Malaysia. Now is the time.

The regulations around this industry monumentally changed in Europe recently: on 14 December 2016, the EU officially authorised insect meal as a source of feed for aquaculture. This new regulation will become effective 17 July 2017. This is a great step forward which strengthen this nascent industry and bring a strong credit to this technology.

To learn more about Entofood, visit their website: entofood.com

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "