The tiny city-state of Singapore, which is roughly the size of San Francisco, is home to somewhere between 1.1 to 1.4 million migrant workers who come from impoverished countries to work in Southeast Asia’s wealthiest country; many work as domestic helpers, cleaners, construction staff, and day laborers. Most do so to send money back to their families.

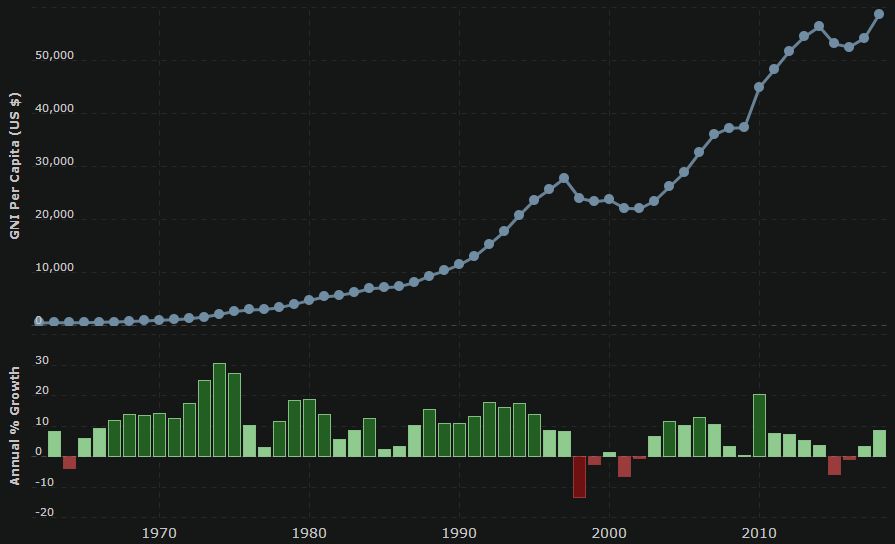

Just four decades ago, Singapore was but a shell of what it has become today. The per capita income was barely $4,700 a year (today, it’s over $57,000). With few natural resources and a small population – both conditions that still exist now – Singapore turned to cheap foreign labour to build out its world-class infrastructure, from the hyper-efficient MRT system to the iconic Marina Bay Sands. Everywhere you turn in Singapore, the toil and sweat of imported labour are on brilliant display.

So, strolling around Singapore today (or before its ongoing lockdown, to be more accurate), with its gleaming skyscrapers, modern conveniences, disciplined citizens, orderly train stations, and famously litter-free streets and sidewalks, you might expect that a nation that so visibly depends on these migrant workers, who comprise about 20% of Singapore’s population, would provide a reasonably comfortable life for them.

As has been laid bare in the last two weeks, however, you’d be very wrong.

The reality of life for a migrant worker

There is no national minimum wage in Singapore, and so many of these migrant workers earn basic monthly salaries starting as low as S$300 (RM918) a month, in a country where the median monthly income for its citizens is S$4,500 (RM13,769); the average monthly salary is about S$3,100 (RM9,485). (For a quick primer on median vs. average, click here.) Much like here in Malaysia, too, oftentimes these workers have to pay an agent or a syndicate a significant fee to even get the job, then they must continue paying a monthly charge to the agency from their salary, though sometimes this payment covers rent and/or food, as well.

One worker, interviewed for a story by the US media, said he paid a whopping S$7,000 upfront to his agency, many times his monthly salary of S$400. Then, his employer takes S$130 off that for food expenses, leaving the worker just S$270 a month, payment rendered for working in construction 10 to 12 hours a day for a minimum of six days a week.

About one-quarter of all of Singapore’s migrant worker population, many of whom are from India and Bangladesh, live in large, densely packed dormitories outside of the city, built specifically for this purpose. Rooms are shared by 12 to 20 men, and each floor, which houses about 200, has a single communal toilet and shower facility. They are shuttled to and from work sites in open lorries, seated shoulder to shoulder. They share closets and clotheslines. They form long queues each day to receive food.

If you think this sounds like a disaster waiting to happen in the face of a highly contagious respiratory virus, you aren’t alone. On March 14, Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower pushed out directives to these dormitory operators titled “Key Actions to Manage Transmission of Covid-19 in All Dormitories.” On March 23, an open letter from a group called Transient Workers Count Too was published in The Straits Times, warning of the risk of a large outbreak among Singapore’s migrant workers.

Too little, too late, perhaps? It’s unclear. But what’s painfully evident is that this is now exactly what has come to pass.

‘We are all living in fear’

The overwhelming majority of the terrible surge in daily new Covid-19 cases in Singapore in the last two weeks are among its migrant workers. When Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong recently announced the lockdown measures would be extended to June 1, he acknowledged the plight faced by these low-wage workers, saying, “To our migrant workers, let me emphasise again: we will care for you, just like we care for Singaporeans. We will look after your health, your welfare, and your livelihood. We will work with your employers to make sure that you get paid, and you can send money home. This is our duty and responsibility to you and your families.”

To some, these benevolent words no doubt ring rather hollow. After all, Singapore has largely been built over the last 50 years by cheap, imported labour. The protections for these workers are few, and usually poorly enforced. The conditions in which many of the workers are forced to live are clearly terrible, hardly befitting a country of Singapore’s wealth and stature.

In a BBC news story, workers interviewed said they were living in fear, knowing how contagious the virus is.

Tommy Koh, a former diplomat and Singapore lawyer, called for reform in the way Singapore treats its invaluable migrant workers, saying “the dormitories were like a time bomb waiting to explode.” He addressed the issue in a Facebook post last week that was liberally shared and forwarded, noting, “The way Singapore treats its foreign workers is not First World, but Third World. The government has allowed their employers to transport them in flat bed trucks with no seats. They stay in overcrowded dormitories and are packed likes sardines with 12 persons to a room.”

In fairness, Singapore’s government has actually taken some tangible steps during the lockdown to help their migrant workers. A 27-year-old worker from Bangladesh spoke to CNN for a story and said he had been provided with face masks, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies, soap, and fresh fruit by the government. He also noted that the government had furnished the workers with free Wi-Fi and extra phone cards so that he and his dorm-mates could at least spend their days under quarantine talking to friends and family back home.

And action has been taken against exploitative employers, as well. Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower has stated that it prosecutes employers who refuse to pay workers, and has also taken action against dormitory operators who don’t adhere to laws and regulations. According to a press release from the Ministry of Manpower, a dorm operator and its director were prosecuted under the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act last year, after living quarters were found to have nonfunctional lights. broken shower taps, and “filthy” living conditions.

The government has also directed that these migrant workers should be paid during Singapore’s lockdown, even if they are unable to work, and has provided subsidies to employers to make that possible. (It is assumed, and hoped, that there is a system in place to check this, so that unscrupulous employers won’t simply pocket the subsidies and leave their workers unpaid.)

The exploitation and mistreatment of low-wage migrant workers is hardly unique to Singapore, but the pandemic has cast into sharp relief the disparity of such an ultra-modern, wealthy nation and its regard for the migrant workers who have contributed so indisputably to its rapid rise – workers who, activists have noted, largely live in a parallel, unseen universe in Singapore.

One such activist pointed out that white-collar expatriates “have rights to family reunification and paths to eventual long-term residency and citizenship, low-wage work permit holders have no such options,” further noting that these migrant workers “aren’t even allowed to marry Singaporeans or permanent residents in Singapore without first seeking permission from the government.“

Kirsten Han, a Singaporean journalist, pointed out that the government sends out daily text messages to residents with updates on the outbreak. New cases are divided into two groups: ‘cases in community,’ and ‘cases among work permit holders.’

“I think splitting the infections into categories along these lines, and telling the population that they are ‘two separate infections’ (as if Covid-19 cares about what passport you hold!) is really problematic,” Han wrote. “It feeds into this whole idea that migrant workers aren’t really part of the community, and continues to feed the idea that they are merely ‘guest’ workers and don’t really count when it comes to discussions about the local population and community.”

In her opinion piece, “Singapore’s new Covid-19 cases reveal the country’s two very different realities,” published in The Washington Post, Han stated, “The reality that Covid-19 so harshly reveals is that there has long been two Singapores: one for citizens, long-term residents, and expatriates, and one for the low-wage migrant workers who provide the back-breaking labor upon which Singapore gleams.”

Many activists are hoping the Covid-19 crisis will spur a real push for reflection and reform in how Singapore values and treats its migrant worker population, with lasting change that will endure beyond the pandemic. Indeed, it is a lesson that many countries – not just Singapore – would do well to learn.

For additional information, visit the Transient Workers Count Too website.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "