With no clear end in sight, Malaysia’s repeated lockdown efforts are devastating businesses across the nation, with the travel and tourism industry feeling that it’s been sentenced to death by a thousand cuts.

On March 18 of this year, as the scope of the growing Covid-19 crisis came into focus, Malaysia enacted a nationwide Movement Control Order (MCO). Though it’s been contracted, relaxed, expanded, and strengthened at various times since then, it’s never fully gone away. Less stringent versions were put into place after the original lockdown expired (following a number of extensions), then those measures were again modified and expanded as the pandemic’s waxing and waning surges have dictated.

Though the initial MCO was incredibly disruptive and wreaked havoc on the country’s businesses and economy as a whole, most people generally understood the need for such a lockdown. The chain of infection in the burgeoning outbreak had to be broken, and the curve of Covid cases had to be flattened.

Well, we did that. Through the combined efforts of government leaders, healthcare and law enforcement frontliners, and millions of conscientious citizens through their everyday actions, Malaysia got an admirable handle on the pandemic. But the coronavirus is persistent and insidious and is not an easily vanquished adversary. That early success was, unfortunately, not to last.

A Short-Lived Rebound, Then a Much Stronger Surge

Many businesses, particularly small ones, suffered greatly during the original MCO, and more than 30,000 SMEs have shuttered for good, according to SSM. (This number was initially placed at over 50,000, but seems to have been amended.) But as we transitioned to less-restrictive measures, there was hope that domestic activity could keep the overall economy and its myriad industries afloat, if not enriched, limping along until international borders begin reopening. Travel and tourism businesses were especially affected by the lockdown, but many held out similar hopes that the country’s domestic tourism market – buoyed by the ‘Cuti-Cuti Malaysia’ campaign – could sustain things until global travel resumed.

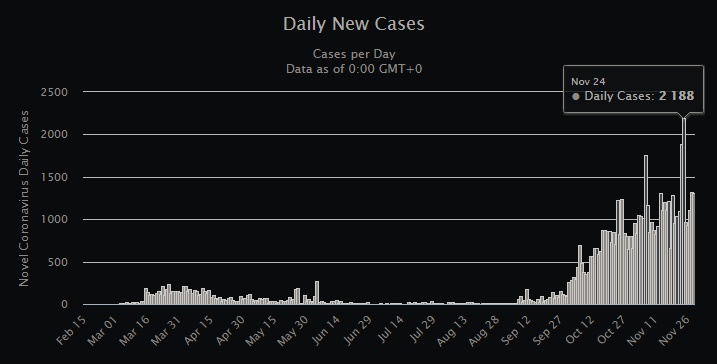

A minor spike in daily new cases occurred in early June but was quickly brought under control, and from that point all the way through to early September, it looked pretty good in Malaysia. Hotel and tourism operators reported a welcome uptick in business in July and August, with many showing their best numbers in months by the end of August, much of it tied to the Merdeka weekend travels.

Mid-September brought another surge in the daily new case count, but given the good work by authorities in contact tracing and identification of clusters, these localised outbreaks were of some concern, but not overly alarming. But then October came, and with it, a significant increase in daily new cases, with the numbers far exceeding those that had been logged in March and April. Back then, only a handful of days saw even as many as 200 new cases recorded. Suddenly, Malaysia was facing daily increases of 300, 600, 800 cases.

Then it really spiked, with back-to-back days in late October each recording over 1,200 new cases. By mid-November, 1,000 to 1,200 new cases a day was a dismal new norm (spiking to 2,188 on November 24), with the cumulative total cases skyrocketing from 11,484 on October 1 to a stunning 64,485 in just under two months. The number of active infections exploded, too, from just 150 active cases in the country on September 5 to a peak of over 14,000 on November 24.

Lockdowns and Langkawi

Even as case numbers soared, authorities had already pulled the panic alarm in the middle of October and enacted a soft lockdown for Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, and Putrajaya – by far the nation’s largest population centre – which mandated no interstate travel, among other myriad restrictions.

Overnight, the sputtering-but-surviving domestic travel market all but evaporated. Hoteliers throughout Malaysia – from Desaru, Johor Bahru, and Melaka clear up to Ipoh, Penang, and Langkawi – saw bookings plunge. No one from outside Greater KL was allowed in, either, so hotels in the Malaysian capital city area saw a similar decline. (Indeed, two notable hotel groups in the city reported to me dire occupancy rates in their various properties in the wake of the implementation, several of which were under 15%.)

The two-week Conditional MCO was then extended by another two weeks, further twisting the knife for outstation tourist destinations. At this time, I decided to go ahead with my already once-delayed trip to Langkawi, in a bid to survey the travel scene there, and talk with shop owners, restaurateurs, and hoteliers. I got police permission to make the trip, and flew to Langkawi on the only flight of the day from Subang airport. Normally there are six or more. In the airport waiting area, with only two flights scheduled – one to Penang and mine to Langkawi – fewer than 20 people were on hand, even half an hour before both flights.

An hour after take-off, I arrived in Langkawi, and suffice it to say, the mood was beyond grim. Many shops are closed – whether temporarily or permanently is hard to say – and a pervasive sense of quiet despair had nestled over virtually everything like a thick fog, from the airport to every former tourist hot spot I visited. At the freshly renovated Langkawi International Airport, only a small handful of domestic flights arrive each day, none of them close to full. One worker at the airport spoke to me of a day at the end of October on which only two flights arrived. Most of the shops, restaurants, and even the lounge at the airport are slumbering behind metal roller doors now.

Pantai Cenang, the island’s most popular stretch of beachfront, lined with restaurants, attractions, souvenir shops, and independent tour kiosks, is all but empty. Langkawi residents stroll around here and there, and the main beach at Cenang had a couple of dozen of locals enjoying the tourist-free stretch of sand, but apart from that, it was a quiet scene. Even places like Underwater World, Cenang Mall, and the large duty-free shops were practically deserted. Neighbouring Pantai Tengah is faring no better, with numerous restaurants and curio shops shuttered, though a few remain open, hopeful workers lingering by the sidewalk signboards, exhorting any passersby they see to come in.

Tourism Troubles

I spoke with a number of hotels and restaurants, who were happy to share their tales of woe, though most preferred not to be singled out in the retelling. A hotel in Pantai Cenang reported less than 15% occupancy on average in the previous two weeks. A restaurant owner told me they were struggling to welcome even a dozen patrons a day. A well-known large resort in one part of the island said they had no guests at all in residence – a stunning 0% occupancy rate that almost defies belief; a manager at a different resort in another part of the island ruefully shared that they had just one room occupied. A watersports operator told me he couldn’t remember business ever having been so bad since he got into the industry. The owners of a lovely homestay told me their property had hosted no guests at all for the entire month of October, and had only one or two bookings scheduled until the end of the year.

The main commercial centre of Kuah, a bit woebegone in appearance even in the best of times, has taken on the look of a largely abandoned ghost town. Local business still goes on, and the banks here of course have their usual foot traffic, but eateries and duty-free shops, reliant on the business of travellers, are clearly struggling. At a large duty-free shop, one of the owners accompanied me as I browsed, urging me to look at this or to buy that. “All of these chocolates are buy one free one now,” she implored, gesturing with a sweeping hand to piles of imported chocolate. “Very good price!” In the end, I bought some discounted Haribo sweets and a taped-together bundle of the proffered chocolate bars that were on 2-for-1 promotion. I had a very nice conversation with the owner, but it all just felt very sad.

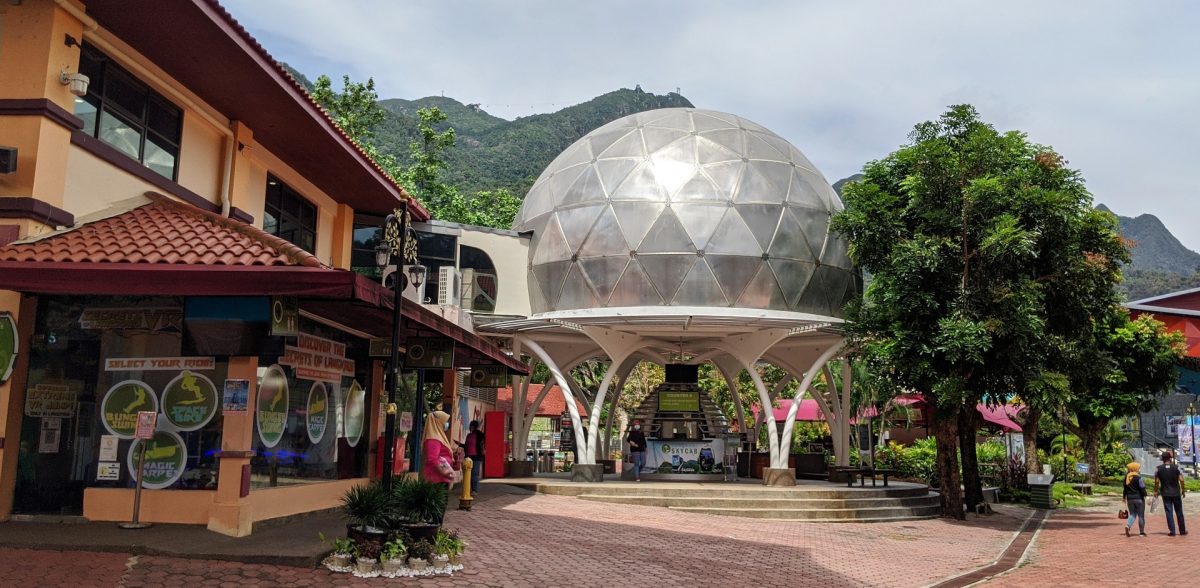

In other places, I almost had the sense I was doing something wrong by even being there, like an ill-intentioned interloper stealthily traversing an abandoned park. I went to Oriental Village, the kitschy but wildly popular tourist centre at the base of Langkawi’s impressive cable car. It was open, and I went through the required measures of having my temperature checked, registering my attendance via my smartphone, and ensuring a face mask was on. But I almost needn’t have bothered, as there couldn’t have been more than 20 people – all local Malay residents – on hand at the sprawling complex. Every single kiosk outside the main entrance (whimsically shaped like cable cars) was closed, the typically open and welcoming hinged doors all closed and brooding amid an empty parking lot. I half-expected to see a lonely tumbleweed blowing across the scene.

Inside, several shops had also closed, some clearly for good. At one, a posted notice, dated in late March, explained optimistically that the closure was temporary. However, the completely vacated shop behind the glass doors – with nothing but a bare concrete floor left – suggested otherwise. It was an eerie experience, and only the occasional glimpse of other people there prevented me from feeling like I was trespassing in an off-limits place.

Extended and Expanded

As I returned to where I was staying from this somewhat otherworldly experience, my phone lit up with messages, telling me that Greater KL’s lockdown would, as of the following day, be extended for another month. Worse, it was to be expanded significantly, encompassing nearly every state of Peninsular Malaysia.

Almost immediately, questions arose, both in mainstream and social media channels. What was driving these decisions? Was there a political calculus? The medical science certainly did not seem to support the widescale CMCO; nor did the recent data. Indeed, the day before the decision was announced, Kedah had recorded three new cases. Johor recorded one. Yet both were nevertheless roped in to this new month-long CMCO. From state governments to business organisations to published statements from doctors, a rumbling of pushback against the decision was felt.

However, the scattershot grumblings have not coalesced into any structured opposition, and at this point, nothing has changed. The Peninsula, apart from the three inexplicably chosen states of Pahang, Perlis, and Kelantan, is under the latest iteration of the CMCO. Malaysia’s tourism trade, already on the ropes, is now feeling a desperate pinch as the latest hammer to be dropped by authorities will make two solid months – at a minimum – of virtually no meaningful domestic tourism being allowed.

The desperate need to not let Malaysian tourism completely die on the vine is an urgent plea now being pushed by a number of related trade groups and organisations in the country. The Malaysian Association of Tour and Travel Agents, representing some 3,400 members (and well-known by the public as MATTA), has expressed serious concern both over the crisis itself and with the lack of clear relief in the 2021 Budget, with Hon. Secretary General Nigel Wong telling me, “Travel agencies and tour operators were one of the first industry groups to really feel the pain as the chain effect of mass cancellations rippled through the entire travel supply chain, leaving agencies to bear the brunt of complaints by angry customers demanding refunds.” Since then, he added, things have largely gone from bad to worse. “Many agencies have already gone into hibernation, some laying of almost 75% of their workforce,” Wong explained. “Surveys indicate that many agencies are expecting to shutter doors if border restrictions persist. The only way recovery can begin to happen is if Malaysia follows some of its more proactive neighbours and initiate managed border openings.”

Of course, it’s not just tours and travel agents that feel the pinch. Without travellers, hotel rooms largely sit empty, too. “Hotel occupancy throughout the country suffered when the CMCO was implemented in KL, Selangor, and Putrajaya, dropping to a low average occupancy of just 20%,” Malaysian Association of Hotels CEO Yap Lip Seng explained to me. “Now, with the almost-countrywide CMCO, the entire industry is being affected again, and this will further push down hotel occupancy. It will likely drop to as low as 5%, much as we experienced during the first MCO in March, and further delay any possibility of tourism recovery.”

It’s safe to say that once we are allowed to travel again, the people whose livelihoods depend on it will be welcoming guests with open arms. We should learn this week whether or not the current CMCO exercise, which is set to run through December 6, will be extended once again, or if Malaysian residents will finally be able to plan some year-end domestic travel escapes.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "