Planes, trains, and automobiles. Now just two of those will be viable ways to get to Singapore for the foreseeable future.

The notion of a high-speed rail (HSR) link connecting Singapore and Kuala Lumpur has been bandied about for a full decade, a tantalising, futuristic transportation option that would see riders zipped comfortably between the two cities in just 90 minutes, travelling at speeds of up to 320 km/hr.

The HSR was initiated through the Economic Transformation Programme as part of the effort to transform Malaysia into a high-income nation. The HSR was envisioned as an alternative travel mode between two of Southeast Asia’s most vibrant and fastest-growing economic engines.

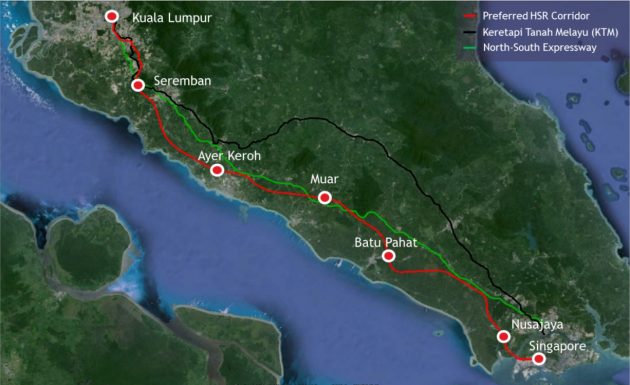

Like any project of this scale, scope, and cost, this one too had its fair share of fits and starts, but until the pandemic hit, progress was ostensibly well underway. There were contract tenders, a dedicated website, public displays of the alignment, press conferences aplenty, and more. The HSR was to have included seven stations in Malaysia – Bandar Malaysia, Sepang-Putrajaya, Seremban, Melaka, Muar, Batu Pahat, and Iskandar Puteri – before reaching its last destination in Jurong East, Singapore.

The HSR entered the public’s view in 2010 as part of the ETP under then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, and was officially given the green light in 2013, and finally signed by both countries in 2016. The service was slated to commence in 2026.

Apart from giving residents in Singapore and Malaysia an additional way to travel between the two hubs, the HSR was intended to boost cross-border business and drive meaningful development of areas along the track’s alignment. Railway-related manufacturers, operators, and other businesses from Japan, China, and a few European countries had expressed interest in the project.

However, after Pakatan Harapan won the election and Mahathir Mohamad became prime minister in 2018, Malaysia requested the suspension of the mega-project as part of the government’s fiscal reforms and reviews. Accordingly, the two countries’ governments suspended the project in September of that year.

Another Covid Casualty

In 2019, it looked like things were getting back on track – no pun intended – but when the coronavirus pandemic hit, along with the collapse of PH and installation of a new government, Malaysia approached Singapore with a new list of amendments and requests. The changes proposed included revising the project structure, alignment, and station design, as well as moving the start of construction up by two years to boost an economy battered by the pandemic. Malaysia also wanted to allow for more flexible financing options, including deferred payments and public-private partnerships.

Reports also indicate that Malaysia wanted to change the HSR alignment to link the line directly to KLIA, a move that Singapore could not have been thrilled with.

Upon review, Singapore rejected the changes, and, unable to reach any consensus, the two countries agreed to terminate the project completely. Malaysia will pay reimbursement to Singapore for costs already incurred, which reports suggest will be in the neighbourhood of RM300 million.

“In light of the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on the Malaysian economy, the government of Malaysia had proposed several changes to the HSR project,” according to the joint statement by Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. “Both governments conducted several discussions with regard to these changes and [were not] able to reach an agreement.”

The statement continued, “Both countries will abide by their respective obligations, and will now proceed with the necessary actions resulting from this termination of the HSR Agreement.”

In the wake of the HSR’s collapse, Malaysia will explore other options for the project, including keeping it within the country. Malaysia is considering ending the line in Johor Bahru rather than in Singapore, something Johor is pushing for, but which has also been derided by critics as being rather pointless. In mid-December, some reports in local media indicated that Malaysia had decided to proceed with the HSR, but without Singapore in the picture.

Was the HSR Project Termination a Good Thing?

Some in Malaysia have tried to spin the project’s cancellation as a “blessing in disguise” and indeed, it’s accurate to say that the HSR has long been a controversial project, which is not uncommon with massive infrastructure projects.

Malaysian Association of Tour and Travel Agents (MATTA) president Datuk Tan Kok Liang asserted that the HSR would have reduced Malaysian airports and cruise ports to being mere feeder providers rather than key transport players.

“With tourism at its lowest ebb, we need more direct flight connectivity to our country’s key airports and cruise ports, rather than through Singapore,” he explained. “If the high-speed railway comes to fruition, tourists and businessmen will start using [Changi Airport in] Singapore as a travel hub. Consequently, major airlines will stop servicing KLIA.”

He concluded, “The HSR, therefore, actually consolidates Singapore’s position as a major transportation hub at the expense of our country’s tourism revenue.”

Malaysia Tourism Council president Uzaidi Udanis agreed, voicing his support for the decision to terminate the HSR agreement.

“Although Malaysia has to pay compensation to Singapore, I think it is reasonable if we weigh the project’s long-term consequences for our tourism industry,” he said. “If the HSR becomes a reality, airlines will prefer to go to Singapore’s Changi Airport rather than to KLIA. This will dampen our domestic tourism market, and make our tourism sector highly dependent on Singapore in the long run.”

Frankly, this seems to be a philosophy somewhat akin to the “Proton strategy” for competition that Malaysia employed back in the carmaker’s formative years. Rather than compete with other brands on merit, the rules were simply changed, effectively rigging the system to give Proton an artificial competitive advantage. Similarly, rather than making KLIA better and providing airlines with more incentives to use the airport as a regional hub, this thinking surmises that it’s better to just pursue strategies that reduce or eliminate direct competition with Changi.

It’s also unclear that these predictions would, in fact, have actually come to pass. Would travellers who are keen to go to Kuala Lumpur really have elected to fly into Changi, then transfer by ground to the Singapore HSR station in Jurong East and take a 90-minute train ride to Kuala Lumpur rather than just flying directly into KLIA to begin with? Sure, this could possibly happen – and the law of unintended consequences would always be in play for a project like this – but its inevitability is certainly questionable.

The current city pair of Kuala Lumpur and Singapore was, before the pandemic, consistently one of the busiest international flight routes in the world, so the HSR’s potential impact on this was also unclear.

A Troubled Economy Could Not Sustain the HSR

Some contend that from an economic perspective, the decision to cancel the HSR was the right one.

Putra Business School associate professor Dr Ahmed Razman Abdul Latiff said termination was the wiser path to take, despite the fact that Malaysia will likely end up paying RM300 million in compensation to Singapore.

He noted that the cost of committing to the project was much higher, anywhere from RM70 billion to RM100 billion, a huge sum for a nation in the throes of economic despair. “Given that the country is facing both health and economic crises at the moment,” he said, “the financial commitment required to continue with the HSR project might not be the top priority for the government.”

Many netizens, however, particularly in KL and JB, took to both mainstream and social media outlets to voice their frustration and disappointment in the project’s demise.

In an NST interview, oil and gas employee Zulkifli Leman, 36, described the decision to terminate the project as a letdown. “As someone who lives in Johor, I am disappointed. I was really looking forward to an upgrade in the transportation system that links the two countries,” he commented, adding, “I still believe that the HSR project will benefit the people and the economy in the long term. The high-speed train was our hope for a modern and efficient mode of transportation.”

Food entrepreneur Salina Abdul Karim, 45, also said she was shocked and disappointed to learn about the cancellation, while saying that she still hoped that certain parts of the project would resume after the economy had recovered.

“Many of my relatives and friends who are residing and working in Singapore had bought houses here when they learned about the HSR project,” she explained. “Now that the project is cancelled, I am sure that they will have to face a different kind of economic burden from the purchased properties.”

The promise of easy connections and reduced traffic jams also seemed to have died on the vine. “The news is not easy for people to accept, especially those who commute daily between the two countries, because they will have to continue to endure the traffic congestion on the Second Link,” she said.

For many, the project’s abrupt termination after so many years of hope and promise is a bitter pill to swallow. For others, it is seen as a good move for a troubled economy and tumultuous times.

Only time will tell how this decade-long saga – from conception to approval to undertaking to delays to recommencement and ultimately to termination – will really impact both countries.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "