Abandoned nearly 50 years ago, Hashima Island is today easily one of Asia’s creepiest sites – but that didn’t stop Japan from opening it to curious visitors.

Not far from the centre of Nagasaki, Japan, lying off the southwest coast of Japan, a tiny island called Hashima was at one time the most densely populated place on Earth. Today, the island has no people, no power, and no running water, and is a testament to what happens to the structures we leave behind as nature inexorably reclaims that which we have built upon its lands.

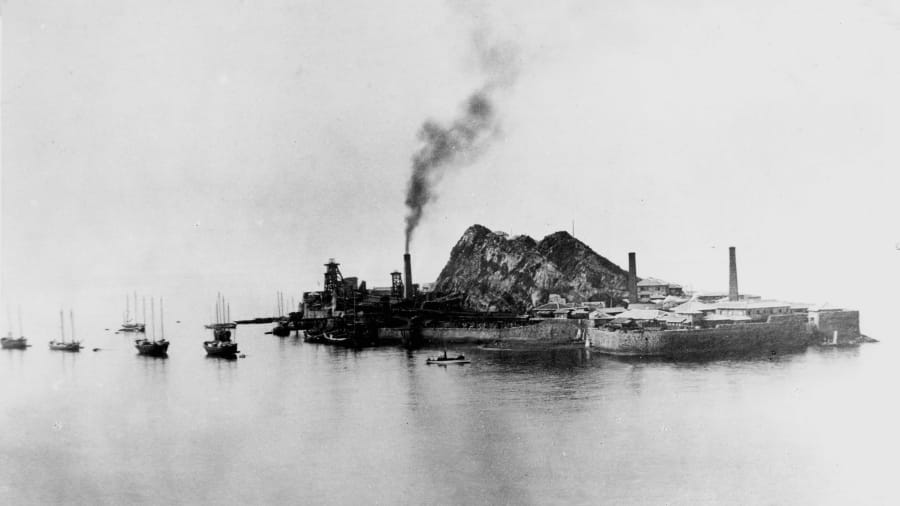

Barely more than a mostly barren rock rising from the sea when undersea coal mines were discovered on this 16-acre island back in 1810, it wasn’t until years later that the prospect of extracting that coal became feasible.

In 1890, corporate giant Mitsubishi bought the island and began extracting the coal, building concrete seawalls, and ultimately tripling the size of the island through reclamation efforts. As the pace of coal mining grew, the ranks of workers needed on the island did, too.

In 1916, Mitsubishi built what was actually Japan’s first large reinforced concrete building (a seven-floor miner’s apartment block), to accommodate the growing numbers of workers. (You would think such a building would be in Tokyo, not on a tiny island hundreds of miles away!)

Over the next 55 years, more buildings were constructed on Hashima Island, including additional apartment blocks, a school, kindergarten, hospital, town hall, and a community centre. For entertainment, a clubhouse, cinema, communal bath, swimming pool, rooftop gardens, shops, and even a pachinko parlour were built for the miners and their families. At one time, Japan’s tallest building – a nine-storey apartment block comprising 241 rooms – was here.

The island in Japanese was called Gunkanjima (軍艦島, meaning Battleship Island). The colloquial name arose from the seawall-surrounded island’s resemblance to the Japanese battleship Tosa when viewed from the sea, especially at a distance. The resemblance was so uncanny that during World War II, Allied forces launched torpedoes at the island, believing it to be a Japanese warship!

At one time, life was abundant on Hashima Island. Grainy photos and even videos still exist of women cooking meals, men returning from the mines, and small children running and playing in the courtyards amid the hulking, spartan buildings of Hashima.

At its peak population in 1959, the small island had the world’s highest population density, with 5,259 people packed onto the 16-acre bit of land, for a density of 83,500 people per sq km. (For comparison, Singapore’s current population density is almost exactly 1/10th that of Hashima in 1959 – now standing at 8,358 people per sq km.)

Notably, no lifts or elevators ever existed anywhere on Hashima Island. Despite the height of several of the buildings, steep stairs were the sole way of accessing the upper floors. If you can imagine the pain arising from wearily climbing floor after floor of concrete steps to reach your tiny apartment after an exhausting day of working in the mines in oppressive heat and humidity, you can understand why the worst of these ascents was paradoxically called ‘the stairway to hell.’

The buzz of human habitation yielded an impressive output here: The mines of Hashima produced a whopping 15.7 million tons of coal during their operational period from 1891 to 1974.

As time went on, however, petroleum began to replace coal as a fuel source in Japan, and during the late 1960s, the mines of Hashima began shutting down. Mitsubishi closed the the island’s mines in January 1974 and began clearing out the dwindling residents of Hashima Island. On April 20, 1974, the last remaining people on the island were relocated.

The tiny island sat abandoned, unpopulated, undisturbed, and largely forgotten for the next 35 years. Access to the island was prohibited, but in 2009, something changed.

HUMANS RETURN TO HASHIMA

The idea of allowing visits to the abandoned industrial island had been mooted a few years earlier, and some journalists were even allowed to step foot on the island in 2005, which had, to that point, been left just as it was in 1974, undisturbed but by nature. Officials at that time planned to build a landing pier and a visitors’ walkway in 2008, but that was delayed due to concerns over safety.

Moreover, it was estimated that any landing of tourists would only be feasible for 160 days per year at the most because of the area’s harsh weather. At last, a small portion of the island was finally opened for tourism in 2009, but more than 95% of the island remains strictly off-limits during tours. According to reports, a full reopening of the island would require a “substantial investment in safety, and detract from the historical state of the aged buildings on the property.”

Today, Hashima Island is increasingly gaining international attention not only for its industrial heritage, but also for the undisturbed housing complex remnants representative of the period from the Taishō period to the Shōwa period. It has become a frequent subject of discussion among enthusiasts for urbanised ruins.

Since the abandoned island has not been maintained for more than four decades now, a number of buildings have collapsed, mainly due to corrosion of concrete-reinforcing members, and also from typhoon damage. Currently, several other buildings are in danger of collapse.

The island gained more exposure with its feature in the 2009 History Channel documentary series Life After People, and of course its inclusion as a filming site for the 2012 James Bond film Skyfall, though largely only for external shots of the island.

DARK TIMES, DISTURBING SECRETS

The tale of Hashima Island is unfortunately not limited to Japan’s industrial rise. During the Second World War, the history of the island is far darker, as Japanese wartime policies exploited enlisted Korean civilians and Chinese prisoners of war as forced labourers on the island.

Past workers have recounted their time with grim details, describing the conditions as gruelling and inhumane. The hot and humid environment of the money – typically around 30°C and 95% humidity – was debilitating, and food was scarce. If the workers slacked, they were beaten.

Made to work under such cruel conditions, it’s estimated by some historians that as many as 1,300 workers died on the island between the 1930s and the end of the war as a result of accidents resulting from unsafe working conditions, malnutrition and starvation, and sheer exhaustion.

In 2015, Hashima Island was named by UNESCO as a World Heritage Historical Site. But that heritage is muddied and a subject of continued debate: Should the focal point of the island revolve around its part in Japan’s rapid industrial revolution or as a reminder of the forced laborers who had to endure such excruciating circumstances?

While the initial bid in 2013 to be included in UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites covered the industrialisation aspects of the island from the 1850s to 1910, it made no mention of the Korean and Chinese forced labourers.

It seemed Japan would rather forget (or gloss over) this troubling chapter from the island’s past. However, the island’s association with wartime slave labour compelled South Korea to formally object to its bid for UNESCO recognition.

South Korea claimed that the official recognition of those sites would “violate the dignity of the survivors of forced labour, as well as the spirit and principles of the UNESCO Convention,” and that “World Heritage sites should be of outstanding universal value and be acceptable by all peoples across the globe.”

North Korea opposed the bid, as well, and China also released a similar statement that “World Heritage application should live up to the principle and spirit of promoting peace as upheld by UNESCO.”

Ultimately, at the World Heritage Committee meeting in July 2015, Japan’s ambassador to UNESCO, Kuni Sato, acknowledged that “a large number of Koreans and others” were “forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites.” She also promised that an information centre would be set up explaining the history and circumstances of the labourers at the site.

In response to this apparent acquiescence, South Korea withdrew its opposition, and the site was subsequently approved for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage list. However, the tensions born from the saga haven’t abated entirely, as Japanese officials repeatedly avoided using the term “forced labour” and declined to refer to the workers as “slaves” – to the disdain of Koreans and Chinese.

Following the WHC meeting, Japan’s foreign minister inexplicably remarked that the UNESCO ambassador’s comment “forced to work under harsh conditions” did not – somehow – equate to or mean “forced labour.”

It was indeed a questionable parsing of words, and predictably, South Korea’s government was not amused. They responded to the bizarre claim by Japan’s foreign minister that Koreans were merely “requisitioned against their will” by saying, “If you look at the larger context, it says that they were taken away against their will and ‘forced to work’ under harsh conditions. No matter how you look at it, the only interpretation is that this was forced labour.”

THE ISLAND’S FUTURE

While some historians and scientists are working to preserve and restore some of the structures on Hashima Island, others are asking, “Why?” The abandoned island is a case study in progress to what happens to buildings and concrete over time. If we want to know how an abandoned city will eventually be reclaimed by Planet Earth, then the desolation of Hashima Island holds many of those answers.

In less than 50 years since its desertion, the island’s buildings are crumbling along with its infrastructure, eroded and in some cases destroyed by wind, saltwater spray, and the sheer weight of time. How long will it be before Hashima is nothing but rubble, eventually overgrown by vegetation? Another century? Two or three centuries? If we start restoring and rebuilding on the island, critics say, we’ll lose all those lessons.

Of course, there is the possibility for both schools of thought to coexist. Even now, visits are permitted to the island, but still, the large majority of what’s there remains off-limits and undisturbed. So there clearly exists a dual-track possibility to restore and preserve a small part of Hashima for its historical value – while leaving the greater part of it to continue its long, slumberous decay into oblivion.

To see the Google Street View interactive tour of Hashima Island, CLICK HERE.