Recent temperatures in Kuala Lumpur have certainly been hot, but regional neighbours to Malaysia’s north are taking the worst brunt of the extended heat wave – and experts predict relief is months away.

One of the most reliable – some might even say boring – features of life in the tropics, particularly near the equator, is how regular and stable daily temperatures are throughout the year. Daily highs and lows don’t vary by huge amounts, and moreover, whether it’s March, July, or December, you can generally count on temperatures to be about the same.

In fact, the equatorial climate is so steady and predictable, idle chatter about the weather doesn’t really feature in society like it does in more temperate climates, where massive temperature swings and volatile weather are a regular part of life.

So when people living in tropical Southeast Asia start talking about the weather – and talking about it a lot – you can be sure something has gone awry.

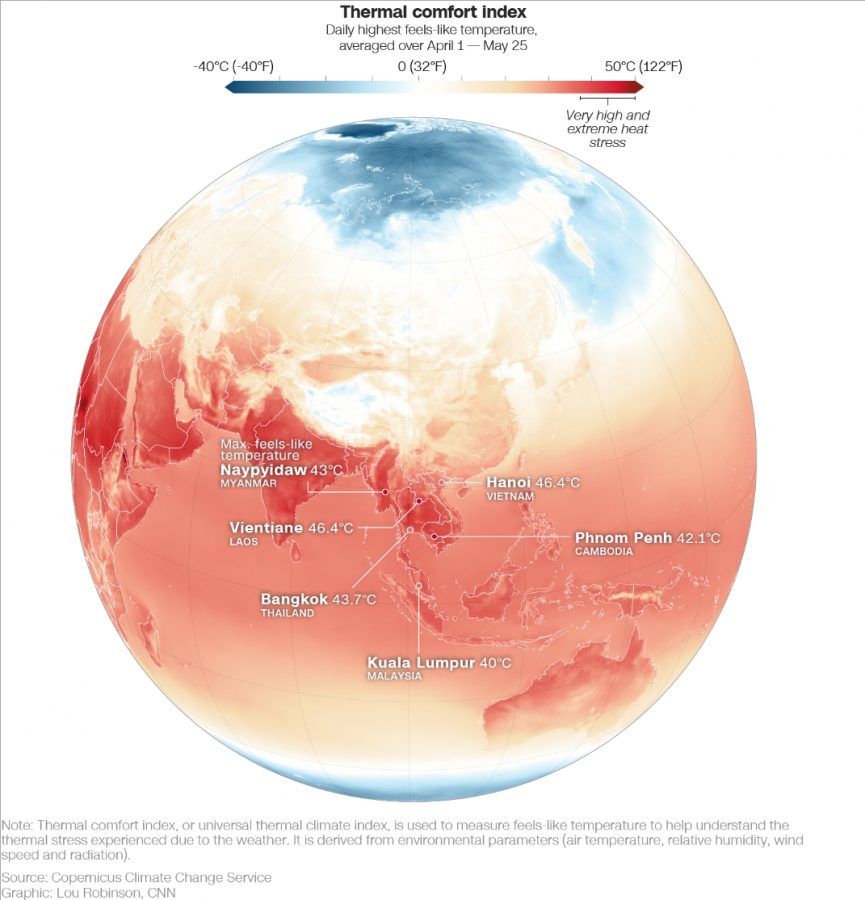

Residents of Malaysia and Singapore, both very near to the equator, are experiencing similar heat stress, but so far, it’s the neighbouring countries just to the north that are really getting the extreme heat.

Indeed, all of Southeast Asia is currently experiencing an unprecedented heat wave, surpassing all previous temperature records in countries like Thailand and Vietnam. In April, Thailand witnessed its hottest day ever recorded at 45.4°C, while neighboring Laos experienced two consecutive scorching days in May, reaching 43.5°C. Vietnam also broke its all-time temperature record in early May, soaring to 44.2°C.

This relentless heat wave, described as the “most brutal never-ending heat wave” by climatologist Maximiliano Herrera, has now persisted into June. Vietnam even broke its hottest June day record on the very first day of the month, hitting 43.8°C, with almost a full month of hot weather ahead.

Scientists from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) report that the April heat wave in Southeast Asia was a once-in-200-years event largely influenced by human-caused climate change. The combination of extreme heat and high humidity has created a deadly situation. Humidity exacerbates the body’s struggle to cool down, leading to severe dehydration, heat strokes, and even deaths, particularly among vulnerable populations such as those with health conditions or pregnant individuals.

CLIMATE CHANGE MEETS EL NIÑO

Exacerbating the longer-term trend of warming, 2023 is predicted to kickstart a potentially strong El Niño period.

El Niño is a weather phenomenon characterized by the warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, which has significant impacts on global weather patterns. It is part of a larger climate cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

During a typical year, trade winds blow from east to west across the Pacific Ocean, pushing warm surface waters towards the western Pacific near Indonesia. This process leads to the upwelling of colder, nutrient-rich waters along the coast of South America, supporting thriving marine ecosystems.

However, during an El Niño event, the trade winds weaken, or even reverse, causing a disruption in the oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns. Warmer waters from the western Pacific flow eastward, accumulating near the coasts of South America. This shift alters the normal temperature and rainfall patterns, affecting weather systems worldwide.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) estimated a 60% chance of transitioning from an ENSO-neutral state to al El Niño state in May to July of 2023. Ongoing climate models continue to suggest this likelihood, with it strengthening as the year progresses. Unusually high temperatures are common with an El Niño event.

“El Niño is normally associated with record breaking temperatures at the global level,” said Carlo Buontempo, director of the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. “Whether this will happen in 2023 or 2024 is not yet known, but it is, I think, more likely than not.”

In addition to elevated temperatures, the annual rainfall here in Malaysia may be as much as 40% lower in some areas of the country this year, which could put palm oil production at risk in one of the world’s biggest producers of the commodity, and a significant driver of Malaysia’s economic engine.

“IT SURE FEELS HOT OUT THERE TODAY!”

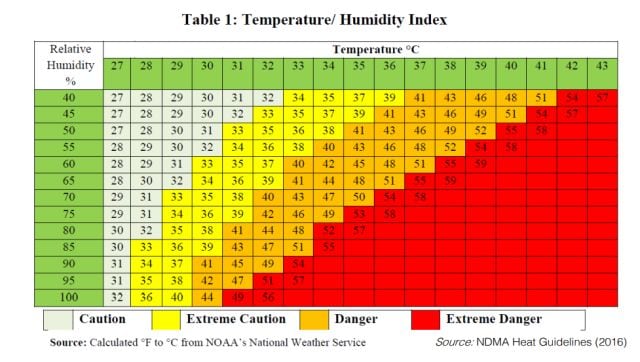

One important metric that health officials look at is not just the actual air temperature, but the apparent, or perceived temperature. The “feels-like” temperature, often called a heat index in temperate countries, factors in both air temperature and humidity, and provides a more accurate understanding of the actual impact on human bodies. Additionally, it’s accurate to say that at equatorial or near-equatorial latitudes, direct sun feels incredibly hot. Cities also have to contend with the urban heat island effect, in which the urban landscape – concrete, steel, dense structures, and a concentration of human activity and associated pollution – experiences notably higher temperatures than rural surroundings.

This all takes a considerable toll, not just on humans, but indeed all living beings… and this year, it’s a regional concern.

Data analysis from the Copernicus Climate Change Service reveals that from early April to late May, all six continental Southeast Asian countries experienced daily perceived temperatures close to or exceeding 40°C. These levels are considered dangerous, posing significant risks to individuals unaccustomed to such extreme heat or those with pre-existing health issues.

In Thailand, the scorching heat wave in April saw 20 days and at least 10 days in May reaching heat indexes of more than 46°C. At this level, thermal heat stress becomes “extreme,” posing a life-threatening risk to anyone, including individuals accustomed to extreme humidity.

Across April and May, several Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Malaysia, experienced multiple days with the potential for extreme heat stress. Myanmar faced 12 such days until Cyclone Mocha made landfall on May 14, bringing some relief but also causing significant devastation.

The heat wave wreaked havoc in the region, resulting in widespread hospitalizations, road damage, fires, and school closures. However, the precise number of fatalities remains unknown, as reported by the World Weather Attribution.

IS IT OUR FAULT? PROBABLY AT LEAST A LITTLE

According to the study, the impact of climate change caused by pollution amplified the heat by more than two degrees in perceived temperature compared to what it would have been without global warming. As the atmosphere warms, it gains a higher moisture-holding capacity, thereby increasing the likelihood of humid heatwaves.

Southeast Asia’s spring weather is getting hotter, and it’s linked to global warming. There has been an upward trend in April heat in continental Southeast Asia since at least 1950. This year, the region’s heat index temperatures averaged 42.4°C in the hottest April on record, as global warming surpassed pre-industrial levels by 1.2°C.

The current heatwave underscores the urgent need for climate action. It has severe implications for the well-being, livelihoods, and vulnerable communities in Southeast Asia. Recognizing the gravity of the situation is crucial in working towards sustainable solutions and mitigating the far-reaching impacts of climate change on the lives of those most affected by scorching temperatures and high humidity.

In Kuala Lumpur, the high relative humidity (70 to 80% RH) tends to make temperatures feel at least 10-15° hotter than the actual air temperature, so on those days – so common of late – when the city sees highs of 34-35°C, you can be assured the heat index is very likely significantly higher than 40°C.

It gets worse, though: If global temperatures continue to rise to a 2.0°C increase overall, these humid heat waves could occur 10 times more frequently, as projected by the study’s findings. This highlights the urgent need for effective measures to mitigate global warming and its associated risks.

For many of us, the rising temps mean more cool showers, higher energy bills with increased use of air conditioning (or more time spent in the malls, perhaps), and a growing appreciation of those regular afternoon thunderstorms. But for some of Malaysia’s most vulnerable communities, long heat waves can be acutely dangerous.

Unfortunately, most climate models don’t really point to much in the way of relief – for Malaysia or the rest of Southeast Asia – for several more months, and given the very real risks posed to people, some groups are urging the government here to look at this as a climate emergency.

Reporting from CNN Asia, Reuters, the World Meteorological Organization, Bloomberg, and the BBC contributed to this article.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "