The tourism tax, which was first introduced in 2017, is currently levied on a flat, RM10-per-night basis for all foreign visitors to Malaysia – and also on some people who aren’t visiting at all!

They say the only sure things in life are death and taxes, and a general disdain for taxation is quite possibly one of the few things nearly all people agree on. But I also think that many, if not most, of us understand why taxes exist. And we accept the imposition of taxes more easily when we see good things arising from their collection.

But it’s a funny old business for sure. I remember many years ago – 1993 to be exact – when my home city of Denver, Colorado was awarded one of two major league baseball expansion teams. For the first two years, the team played in the city’s football stadium since the seasons for the two sports don’t really overlap. The fields for baseball and American football are, of course, completely different, so a lot of adjustments had to be made. Calls quickly began mounting for a dedicated baseball stadium, so accordingly, for the six-county area surrounding Denver, a tiny sales tax increase was proposed to fund the stadium’s costly construction. It was only 0.1% – just 1¢ for every $10 spent, the pitch proclaimed – and voters passed it. A genuinely beautiful new $300 million baseball stadium was built in downtown Denver, just over half funded by that tax, and in April 1995, Coors Field opened with its first game. Now, nearly three decades later, the stadium still stands.

Curiously enough, however, that 0.1% tax increase – ostensibly imposed to fund the construction of Coors Field – also still stands (albeit under a fresh new name). As many governments have discovered, once that magical tap of delicious tax revenue is turned on, it’s really hard to muster up the political will to turn it off.

TAXING THE TOURISTS

The one tax that I would very much like to see shelved here in Malaysia – or at least reviewed and modified – is the loathsome ‘tourism tax.’ Although many municipalities impose such taxes in some form or another, the way in which Malaysia levies it on a nationwide basis could probably use some tweaking.

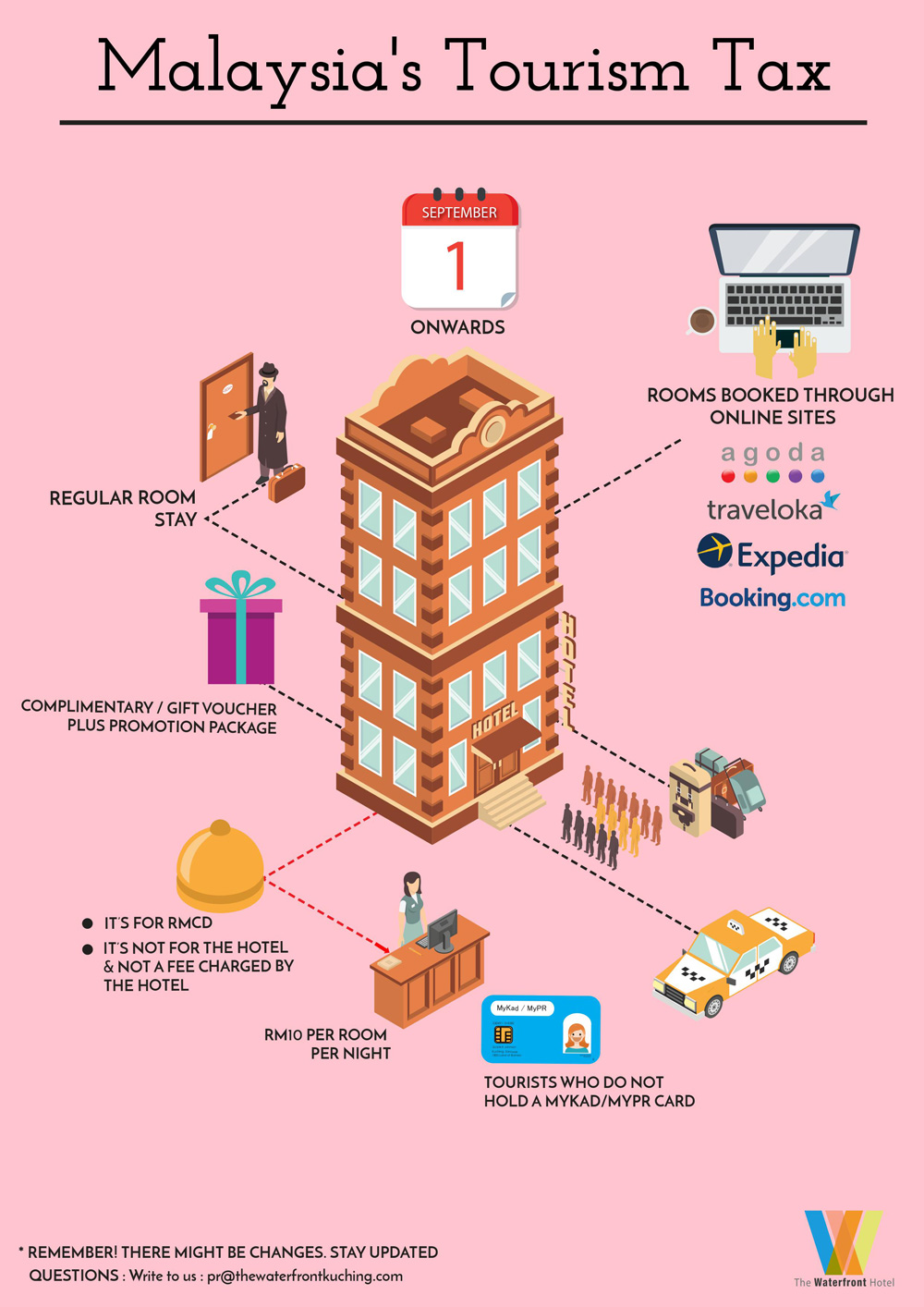

No matter where you go in the country, no matter the room rate of the lodging in which you stay, a flat RM10 per room, per night tourism tax is levied, and innkeepers are required to collect this charge in full and typically upfront (though not always), separate from the bill paid at check-out. It is loudly and clearly announced, too, often noted on a prominent placard at the front desk: this is a tourism tax. Only Malaysian citizens and permanent residents are exempted. (More on this later.)

Does this not seem a bit unwelcoming and unfriendly, as though tourists are almost being openly penalized for choosing to come to Malaysia and spend their money? Officials have said that “most of the money” collected from this tourism tax, which is a significant haul, is used to further promote the country to other tourists, which just seems… odd. A tourist comes to visit and explore Malaysia and spend their money here, and they are taxed specifically so that more tourists can be enticed to come, and then also get taxed for visiting? To my mind, a country should pay, from its own general budget, for promoting itself overseas, not the tourists who have already chosen to visit.

Think of it in a different way. You go to a restaurant, but before you are taken to your table, a RM5 per dish charge is demanded and collected. It doesn’t matter if your selection costs RM150 or RM20. The same fee applies – RM5 per dish. “What is this for?” you ask. “Well,” they explain, pointing to the sign, “it’s our dining tax. We collect this cash from you, then use it to advertise our restaurant so we can get other diners to come. When they do, we’ll collect the same fee from them, then use that to buy even more advertising.”

Would this not elicit outrage? And wouldn’t most diners simply decide to eat elsewhere next time? I feel this is a pretty fair analogy for Malaysia’s tourism tax.

Does it bring in a lot of money? It surely does – early estimates of over RM100 million per 10% in occupancy rate were floated (e.g., about RM654 million for average nationwide occupancy rate of 60%). But is it good policy? That remains an open question.

Surely there must be a better way. Perhaps a blanket ‘occupancy tax’ that is levied universally, and on a modest percentage basis. Even on its face, this seems more equitable, because while paying an extra RM10 per night at a hotel whose rates start at RM900 might not seem like a big bite, how does that translate to paying the same extra RM10 a night for a room that’s RM80 a night? One guest is paying about 1.1% in tourism tax, while the other is paying 12.5%. Additionally, the tax penalty grows if a tourist stays longer in Malaysia, presumably spending more money and adding to the economy all the while. Seven nights? Well, that’ll be RM70 extra, please.

Tourism industry players ramped up calls in 2018 to abolish the tax, which they said was too “in your face” and counterproductive to the goal of stimulating tourist spending. Agencies and tourism groups decried the charge en masses, saying it was an “unnecessary burden” on both tourists and on accommodation operators. Despite months of pleading, however, the government pointedly said it had no intention of removing the controversial tax.

After all, the lucrative tap had been turned on, and just as in Colorado, officials found it much too tantalising to turn off.

BUT IT’S NOT JUST FOR TOURISTS

Possibly the most frustrating thing about this so-called tourism tax is that it is cheerfully imposed on working expats and resident MM2Hers, too – people who are in no way tourists in Malaysia. I’ve lived here for 15 years. I work here, I pay taxes here, I spend money here literally every day, contributing to the country’s economy. And yet, if I travel anywhere within the country, and check in to a hotel, I am asked to pay a tourism tax.

Like several other expats with whom I’ve spoken about the issue, I flatly refuse to pay it, explaining that I am not a tourist, but rather a long-time resident. Of course, I realize it’s not the hotel’s doing, and I tell them that – they’re simply executing Ministry of Tourism policy.

But perhaps it’s time to revisit that policy, and either include residents with long-term visas on the exemption list, or rethink the tourism tax approach altogether. Experts more knowledgeable than I have decried tourism taxes as ‘bad tax policy,’ saying that it shifts the cost burden unfairly, creates negative effects on consumers and business owners, and hinders the effective promotion of a destination – exactly the opposite effect intended. One comprehensive study found that a 10% increase in tourism tax resulted in a 5.4% decrease in tourist demand.

Moreover, many municipalities which do impose a tourism tax do so to help fund the infrastructure and attractions that tourists enjoy, preserve the environment, or encourage the development of sustainable tourism practices. Some even use the funds to pay for insurance policies to provide an umbrella of protection for visitors in the event of injury. And of course, in some instances – in this era of growing overtourism – some destinations impose taxes simply to disincentivize visits.

But not many places explicitly levy taxes on tourists for the purpose of funding the destination’s tourism marketing goals! And most places tend to impose these taxes a bit more discreetly or indirectly, working them subtly into international airline fares, occupancy taxes, or such.

TIME FOR A REVIEW?

Thailand, which in February 2023 approved a controversial and deeply unpopular 300-baht ‘tourism fee’ for visitors arriving by air (150 baht for land and sea arrivals), did not announce at the time exactly when it would be implemented. In mid-December 2023, they announced it would be postponed indefinitely, ‘until the industry recovers.’

Maybe a rethink of a policy that explicitly taxes tourists for choosing to come here is worth considering for Malaysia, too – and certainly a reversal of treating and taxing resident expats as tourists is in order.

Or maybe there’s just a better way to implement these taxes. If levied as a much lower, percentage-based occupancy tax across the board, it would not only be fairer, it could potentially even generate more revenue, as nobody would be exempt. And why should they be? After all, a Malaysian who lives in KL and visits Kuching is still very much a tourist. And if the funds are used to bolster and improve tourism facilities and keep places clean and sustainable, then locals derive every bit as much benefit from that as tourists – if not more!

Tourism is too important to Malaysia’s economy to implement flawed or unsustainable policy. The country has an abundance of incredible tourism assets and derives immense benefit from tourism, so it’s clear that adopting well-thought-out approaches to managing the resources and funding their upkeep will always be of critical importance.