Too often overlooked, Fraser’s Hill is sited along the border of Selangor and Pahang states, and while it was once a centre for convalescence, today it’s one of the Peninsula’s most leisurely highland getaways.

Fraser’s Hill, one of a handful of hill stations established by the British, provided a cool retreat from the oppressive climatic conditions that some colonialists experienced in the Malaysian lowlands. While tin had already been mined on the hill in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it wasn’t until near the end of World War I that there was renewed interest in developing the site perched on top of the Titiwangsa Range, some 100 km from Kuala Lumpur.

History has it that in 1917, the Right Reverend C. J. Ferguson-Davie, the then-Anglican Bishop of Singapore, was hiking in the hills with friends when he realised the area’s potential as a cool holiday retreat. In 1909, Singapore had become an Anglican diocese covering the Straits Settlements, Peninsular Malaya, Siam, Java, Sumatra, and adjacent islands, with Ferguson-Davie as its first bishop. The Diocese of Singapore and the Diocese of West Malaysia only became separated in 1970.

One of the bishop’s immediate priorities was to identify suitable refuges for soldiers who needed a place to convalesce after serving in the war. Fraser’s Hill was identified, and within a few years, three convalescent homes were opened on Fraser’s Hill.

REGIONAL MOUNTAIN RETREATS

At the end of WWI, other mountainous locations throughout the empire were also established as venues for ex-servicemen and women to recuperate. The potential for Fraser’s Hill to be used as a mountain retreat was identified by the bishop while he was holidaying at the Gap Resthouse with A. B. Champion, the Chaplain of Selangor. Both clerics had set off from the Gap for some recreational hiking and reportedly, to search for the remnants of the tin mining operation at the hill summit.

Southeast Asia’s first holiday resorts were mostly mountainous regions, and they became known as hill stations. Malaysia has four such locations: Penang, the Cameron Highlands, Fraser’s Hill, and Maxwell’s Hill (now Bukit Larut). In Vietnam, the French established Dalat, the Dutch settled on Bogor in Indonesia, and the British settled in Maymyo (now Pyin U Lwin) in Burma (now Myanmar).

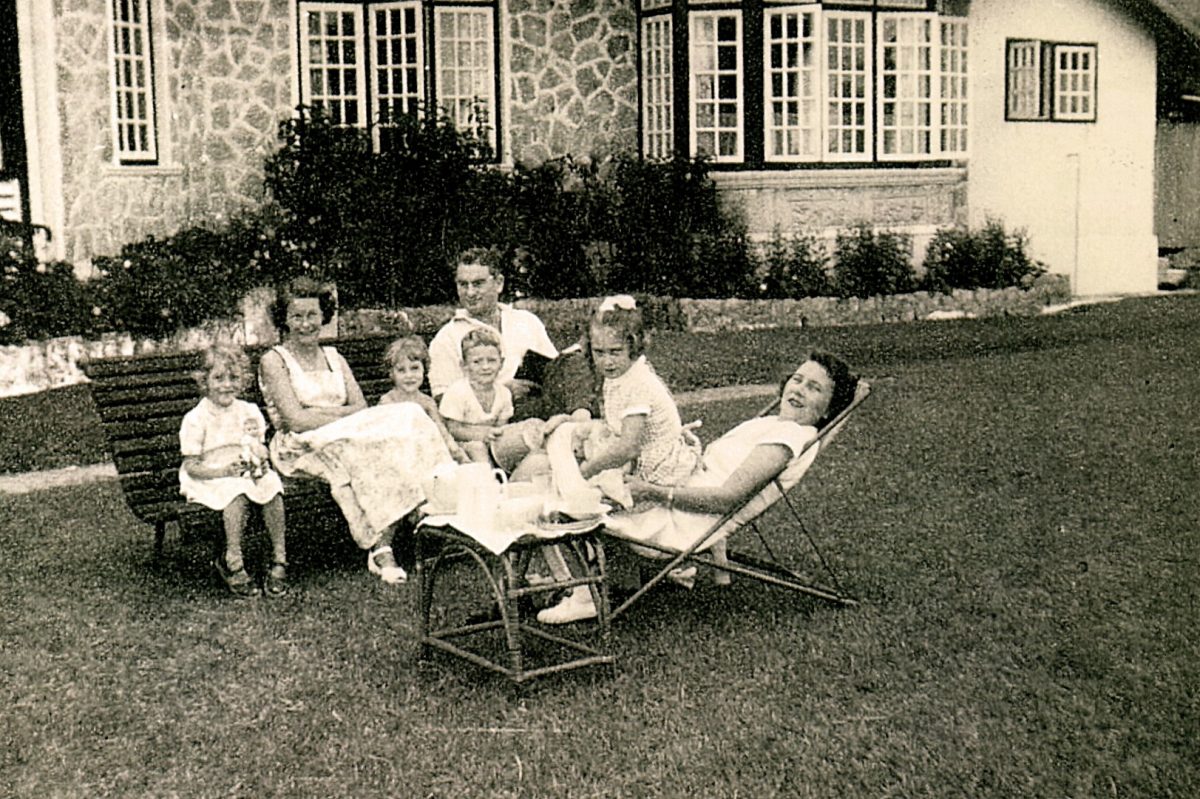

Most of these hill stations have fascinating histories and settings that resemble distant lands that were intentionally created by the colonialists to remind them of life back home. The British set about erecting Tudor Revival bungalows (Mock Tudor or, in Singapore, the Black and White House) based on stone and wood buildings from the Tudor era.

These homes were set among gardens planted with temperate plants, and their interiors often featured an open fireplace. On cool days, colonialists could retreat for a cream tea of scones, clotted cream, and strawberry jam after a round of golf. No doubt, a glass of sherry was consumed prior to dinner, and after supper, the men would adjourn for a snifter of brandy and maybe a spot of billiards after an announcement had been made that jackets might be removed.

A THERAPEUTIC SITE

It was the possibility of setting up convalescent homes, or sanatoriums, that aroused interest in Fraser’s Hill. Firstly, it’s worth reflecting on life in Europe and Malaya at the time. Up until the mid-19thcentury, overseas travel for most was out of the question, and private journeys were really only the domain of the wealthy. Globally, Thomas Cook is regarded as the instigator of mass tourism when he realised the value of the evolving British rail network in transporting all classes of people over relatively long distances (‘now everyone can travel’).

The European rail network was quick to follow, and by the late 19th century, tourists could easily move around the continent. Concurrently, there was a belief among the medical profession that mountains, especially the Swiss Alps, were ‘a place of healing.’ This ensured the Alps became a favoured venue, especially for the treatment of lung diseases.

High-altitude fresh air had a therapeutic effect on patients and soon gave rise to health tourism in Switzerland. The curative regime at the health resorts involved drinking fresh spring water, hydrotherapy, and, of course, inhaling the pure mountain air.

The first organised holidays to Switzerland were offered during the latter part of the 19th century by Thomas Cook and Lunn Travel. Initially, tourism in Switzerland was exclusively for the rich until it became more widely accessible in the 20th century.

Tuberculosis (TB) had reached epidemic levels in Europe in the 19th century, with a mortality rate as high as 900 deaths per 100,000 population per year in Western Europe. Between 1851 and 1910, around four million people died from TB in England and Wales – more than one-third of those aged 15 to 34 and half of those aged 20 to 24.

All this must have been foremost in the mind of Ferguson-Davie when Fraser’s Hill was proposed as a restive holiday destination in Malaya. The bishop submitted a report to the government authorities to establish the highlands as a suitable place for soldiers to recuperate on their return from the war.

His ideas were considered and accepted, with the initial work on the hills beginning in 1918. This could not have been timelier because there was an outbreak of influenza as World War I came to an end in 1918. The countries involved in the war suppressed news of the influenza outbreak in order to maintain morale among the troops. However, journalists in neutral Spain reported on it, leading to its misnomer as the Spanish Flu. K. K. Liew’s article, Terribly Severe Though Mercifully Short: The Episode of the 1918 Influenza in British Malaya, is an insightful read into the devastating impacts of the influenza on those living in Malaya at the time.

The Malayan population came into contact with the influenza as troops, officials, and travellers returned from Europe. Almost 40,000 people reportedly died from the pandemic, with this being even more dramatic than one might think, as the figure represented one percent of the population at the time. Then, expats must have been keen to escape from the influenza-infected lowlands to the cool, clean air of destinations like Fraser’s Hill.

A HEALTHIER ENVIRONMENT

One of the principal reasons behind the development of hill stations was the belief that these high-altitude outposts provided a healthier environment. A week spent in the cool mountain air, playing golf, hiking, and relaxing with other expats was ideal for heart-weary colonialists. It’s also worth remembering that it was then almost impossible for expats to ‘escape’ for the weekend; there were no short breaks to Phuket or Bali available at the time. Holidays or weekend escapes would have been spent within Malaya, where the transportation infrastructure was also quite limited.

Not only were the hills suitable for the convalescing members of the British military, but government officials and the management of large private corporations also recognised their potential for rest and recreation for their staff, many of whom were expatriates.

Mr. F.W. Mager, Pahang State Engineer, was instructed to survey the area and to commence construction of a new access road from the Gap to the Fraser’s Hill summit. Fraser’s disused tin mine was to be the centre of the resort, with the wide valley earmarked for a golf course that is still in use.

The hill resort was officially opened to visitors in 1922. Buildings soon sprung up, built in the ‘colonial style’ between 1919 and 1957, and many still stand, with 46 officially designated as heritage buildings. These include British government bungalows built to house officials of the administration; private bungalows for use by senior company staff employed in trades such as tin and rubber; and public buildings including the post office and the police station.

CONVALESCENT AND COSY

Three sanatoriums, or convalescent homes, were established, with one still intact and operating as the most welcoming and cosy – Ye Olde Smokehouse, a colonial boutique property with just a handful of rooms, a bar, and a restaurant.

After the horrors of World War I, many ex-soldiers returned to civilian life and employment in Malaya, principally as public servants, plantation managers, or tin miners. Funds were raised in the United Kingdom to honour the service of the returned soldiers by providing retreats where they could rest and relax and, in some cases, recuperate.

The British Red Cross Society and the Order of St. John of Jerusalem raised funds to construct a number of buildings on Fraser’s Hill. These were to be sanatoria for those men and women of the Imperial Forces who served between 1914 and 1918 and their dependents. The Red Cross House, now Ye Olde Smokehouse, opened in 1924.

Victory Bungalow on Lady Maxwell’s Road opened two years later and featured a lounge, dining room, sitting room, and two double bedrooms on the ground floor, and a sitting room, veranda, and four double bedrooms upstairs. Booking priority was given to those ex-service personnel who could present a medical certificate for their own health or that of a family member. When opened in mid-1926, the building was originally called Convalescent; however, this name was later adopted by its sister building, which opened in January 1927 in the Selangor part of Fraser’s Hill (the Selangor-Pahang border bisects the hilltop settlement).

Rules were put in place at Victory, and no doubt the others. These included rule number nine: ‘the staff consists of a servant in charge, a cook, and two water carriers; visitors are requested to bring their own personal servants,’ and rule number 10: ‘visitors who bring amahs or ayahs and wish them to occupy a bedroom must provide their own beds, mattresses, and bed linen. In no case will an amah or ayah be allowed to make use of any bed or bedding provided in the house.’

Maintenance has not always been a priority for the bungalows and public buildings on Fraser’s Hill, and sadly, Victory is now empty, derelict, and probably well beyond restoration as the ever-encroaching jungle has taken control.

Convalescent (now Rumah Rehat Sri Berkat), on Padang Road in Selangor, isn’t quite as derelict, but it appears to be just hanging in there. This means Red Cross House is the only former convalescent home that is still habitable.

YE OLDE SMOKEHOUSE

This small colonial hotel that originally opened as the Red Cross House was built by the Department of Public Works, and its first guests checked in during the middle of 1924.

The property reverted to an inn some years later, and in 1988, it began operating as Ye Olde Smokehouse Fraser’s Hill (smokehouse.my). Since then, it has offered comfortable country house hospitality with 14 rooms, a lounge, a restaurant, and a bar. The property offers all the charm of an old English inn, with the suites having good facilities, including en suite bathrooms.

Ye Olde Smokehouse offers a nostalgic English experience and is one of only two places on the hill to enjoy an alcoholic beverage. Beyond a nice tipple, guests can enjoy afternoon cream teas of freshly baked scones, strawberry jam, cream, and a pot of Malaysian tea. There is a small bar with a log fireplace and an adjoining restaurant that serves traditional English fare. Diners can expect traditional English fare such as Mulligatawny soup, beef Wellington, fish and chips, and sherry trifle.

The interiors are circa 1920, with several retaining some original furniture. Mod cons are limited, but that’s the point of staying here; it’s a journey back to a more peaceful and uncomplicated era.

Being of a bygone era, Fraser’s Hill faces a dilemma. Its development appears stifled as tourism numbers dwindle, followed by expenditure on maintenance also lapsing, and then still fewer people visit. Now that exotic regional destinations are within many people’s reach, nearby hill stations don’t have the magnetic appeal they once had.

Fraser’s Hill will especially appeal to those who enjoy relaxing and making their own fun in a cool location. Book a room at Ye Olde Smokehouse and travel here with an open mind to enjoy a comfortable stay in cosy accommodation where life moves at a decidedly slower pace.

While several buildings are designated as heritage, many visitors may be puzzled as to what this means, as most are poorly maintained and sadly falling apart. One building was even pulled down a few years ago, so its heritage status doesn’t appear to have offered much protection. If there were ever a Malaysian setting trapped in a time warp, it would be Fraser’s Hill. While its slow pace of life and general lack of modern facilities may not have universal appeal, others will enjoy the refreshingly cool and unhurried hilltop setting.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "