Malaysian tardiness, often viewed as a cultural quirk, may actually reflect the nation’s polychronic roots, where flexibility, relationships, and collective values shape perceptions of time.

It’s a social necessity for one to get used to Malaysian tardiness. More than once I’ve been to surprise parties where attendees turned up after the guest of honour themselves, fumbling around with humble apologies upon their arrival, but none of them are ever riddled with guilty remorse. Thankfully, most have the courtesy to inform if they’re late beforehand (“I’m on the way!”), but even if they don’t, everyone else is prone to shrug and say, “Okay lah, that’s just Malaysian timing,”

Yes, we Malaysians have even gone so far as trademarking our tardiness. Malaysians definitely even take pride in it by a fair amount, although there’s certainly a portion of the population that refuses to let it become an accepted cultural habit.

Let’s answer the question once and for all: why are Malaysians always late? The most common and easiest answer – traffic – doesn’t explain why people fail to accommodate for it and amend their schedule to beat it the next time. Or, could it be that we’re just a little too lenient with tardiness?

For a planet where everyone is bound to the universal rules of a clock, it’s incredible how cultures can differ in the way they perceive those rules and the concept of time itself. To distinguish those differences, the social psychologist Gerard Hofstede proposed a theory known as time orientation, which supposed that a culture fell somewhere between two types of time orientation: long-term and short-term.

Long-term oriented cultures tend to emphasize on planning for the future and working towards their goals. They consider every moment precious and crucial to getting things done. This would mean that short-term cultures, on the other end of the spectrum, are relatively lax. Seeing more uncertainty in the future, they tend to value past or present experiences, preferring to live ‘in the now’ and working with what they already know. You could probably guess which side Malaysia leans more into.

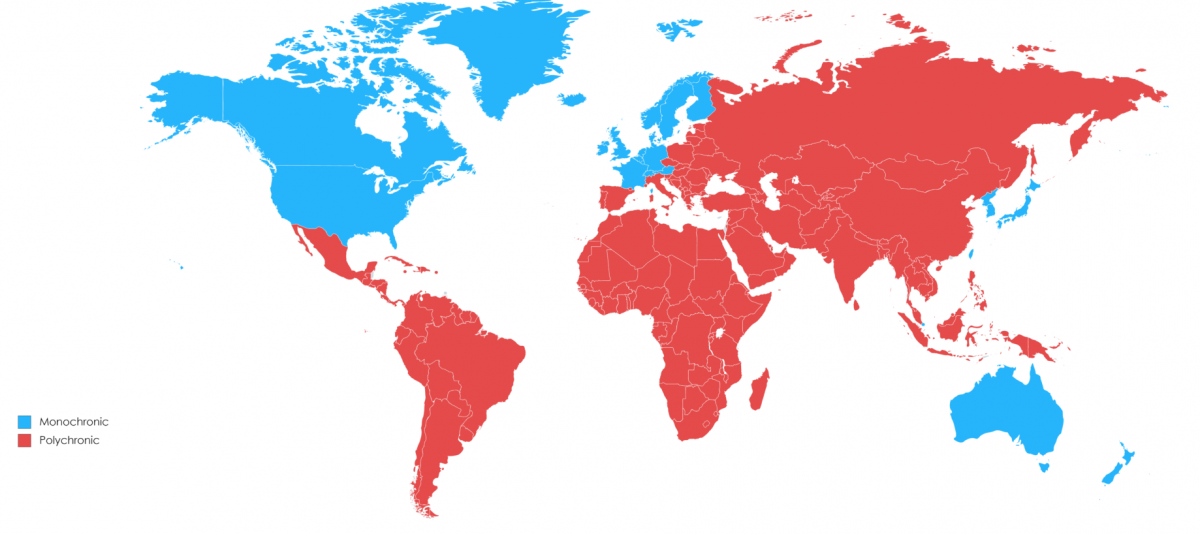

Like most Asian and African cultures that are short-term oriented, the temporal inclinations of Malaysians are characterized as being polychronic. Westerners tend to be monochronic – they operate on time as a fixed commodity that shouldn’t be wasted. As the saying goes, time is indeed money for them. They tackle their tasks one by one and strive to be efficient with the hours they’ve allocated. For those reasons, monochronic cultures usually focus less on interpersonal relationships for the sake of being prompt with their schedule. They don’t stay for small talk or try to keep up with anything else that isn’t practical to getting things done.

Polychronicity is often found in more collectivistic cultures. For such people, no one task or event is monofunctional. They are a simultaneous activity, often done alongside building relationships and keeping the peace in their environment. Polychronic cultures tend to view their schedules as fluid and adjustable to their objectives. If monochronicity lets time dictate the work, polychronicity sees this the other way round. For example, if employees were to find themselves in deep focus, they’re willing to overrun their clock-out time to take advantage of their sudden productivity.

This also applies to leisure. So despite the start and end times stated on an invite card, Malaysians don’t really consider the party started until everyone has arrived. And this means that tardiness can be easily pardoned – or more accurately, isn’t taken as a violation in the first place. Of course, all these are a subconscious social rule; the way polychronic people move from one task to another follows an internal sense. If you’re having a good time with an old friend, neither of you would feel the rush to end the hangout.

Unexpectedly, further reasoning behind chronemic differences across culture can be credited to weather. In colder countries, the monochronic time-based orientation was naturally adopted because daylight was sparse and their frame of opportunity for doing things was tangibly limited. This may explain why places like Japan, although a collectivistic culture, still contain strong monochronic characteristics about punctuality. Meanwhile, hot-climate regions don’t have this same problem all year round, so people could see their events in the day as relative to one another, rather than to a clock or an impending early sunset!

So perhaps Malaysian tardiness isn’t merely a casual disregard for time; it’s a reflection of a cultural identity rooted in polychronicity, where relationships and flexibility often outweigh the rigid dictates of the clock. This easygoing approach is influenced by deep-seated traditions, social values, and even climate, making time fluid rather than fixed. While this may frustrate the monochronically inclined, it also reveals a society prioritizing connections and adaptability over punctuality… a uniquely Malaysian balance of life.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "