What are the challenges of unchecked social media, and what can be done to foster healthier, more authentic online connections?

According to a study referenced by an article in The Atlantic, your social life has a fixed limit.

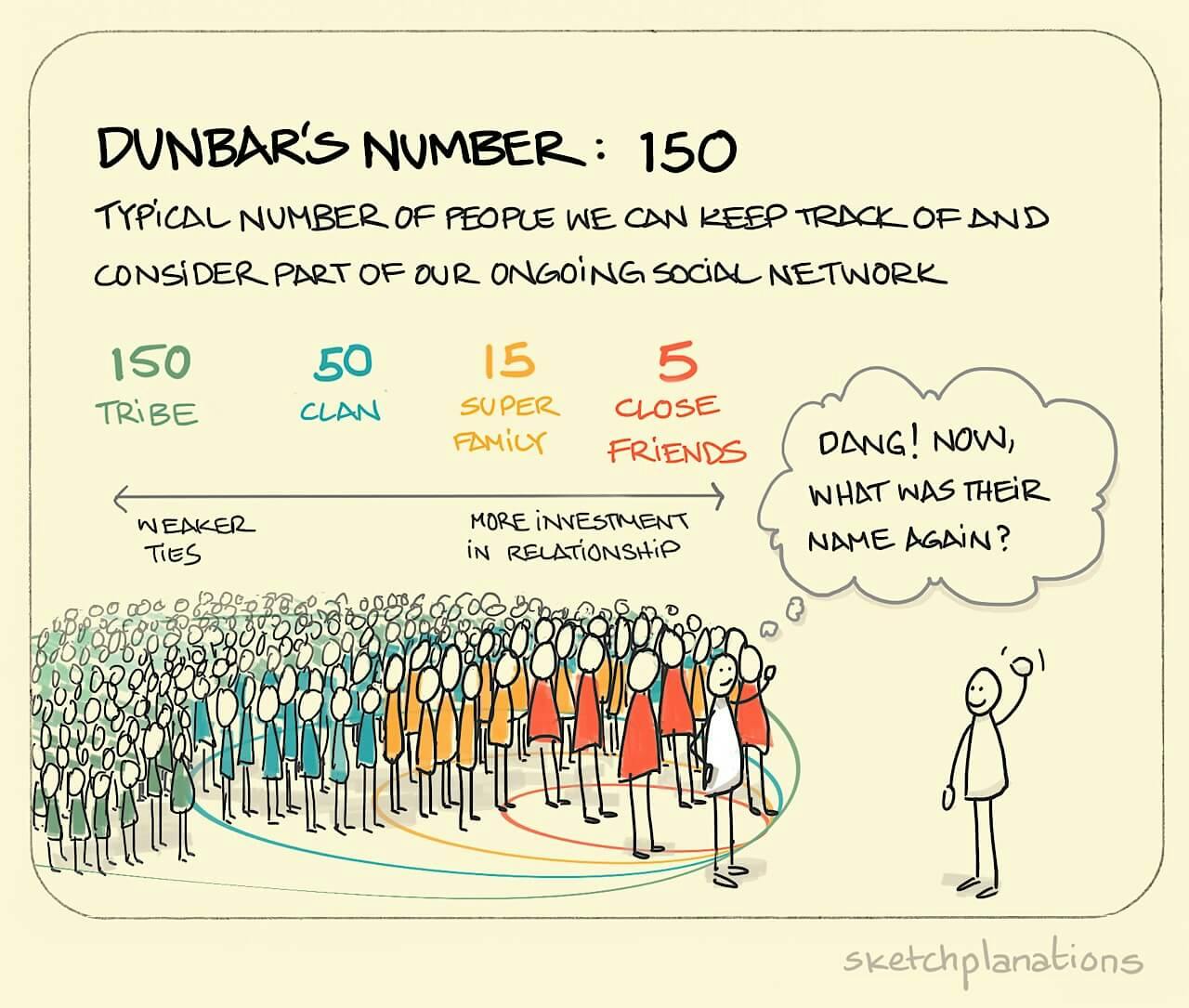

British psychologist Robin Dunbar’s theory suggests a cognitive limit to the number of meaningful relationships we can maintain: 150. Dubbed “Dunbar’s number,” this represents the people you know well enough to greet without hesitation, even in unexpected settings like an airport lounge. Within this group, intimacy exists in layers; think of it like concentric circles, radiating outward, from five to 15 close friends to the broader 150 connections. Beyond this number, relationships tend to dilute sharply in both quality and sincerity.

Despite some criticism of the theory, its intuitive appeal has made it influential. Yet, modern social networks blatantly disregard Dunbar’s premise. Online life is all about maximizing the quantity of connections without all that much concern for their quality. A digital “meaningful” relationship might provide entertainment or utility but rarely involves true emotional exchange. The net result is that, in one of life’s great naming ironies, social media is in fact making us considerably less social. Can that somehow be changed?

THE CONSEQUENCES OF CONSTANT CONNECTION

Before the internet, our social interactions were more limited. Conversations occurred face-to-face or through small groups, and public discourse was often mediated by organizations like media outlets or governments. Today, social media has given individuals unprecedented tools to publish and amplify their voices, removing traditional gatekeepers. While this democratization of communication fosters creativity and diversity, it also opens floodgates to misinformation and harm.

The ease of sharing online has contributed significantly to radicalization, scams, and digital toxicity. Platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter/X have enabled bad actors to spread divisive content far and wide. People’s lives have been ruined over social media posts; marriages ended, jobs lost, friendships strained. The internet’s lack of moderation has transformed it into a breeding ground for extremism and exploitation. Even Instagram and TikTok are ripe for disinformation.

A key question emerges: should people have unrestricted access to communicate with such vast audiences?

Or, as one analysis put it, “It’s long past time to question a fundamental premise of online life: What if people shouldn’t be able to say so much, and to so many, so often?”

THE MYTH OF DISINTERMEDIATION AND THE PROBLEM WITH MEGASCALE

Social media’s false promise, right from the start, was that it would eliminate middlemen, giving power directly to individuals, a concept called “disintermediation.” However, in reality, it simply replaced traditional intermediaries with tech giants like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. Unfortunately, these companies operate not as communication facilitators but as data harvesters. User activity fuels targeted advertising, making “engagement” their ultimate goal—and the bigger the user numbers, the better for their bottom line.

For those users, meanwhile, engagement metrics—likes, shares, and views—have become social media currencies, frequently driving users to prioritize quantity over quality. A viral post may create chaos but is often considered a success within the platform’s framework. Consequently, the sheer volume of online content has become a problem, with platforms struggling to moderate it effectively. And beyond the huge numbers making it a challenge, human content moderation (as opposed to AI moderation) on many platforms is such an awful job, given the horrific nature of some of the posts that must be removed, that it effectively amounts to mental and emotional trauma. (Editor’s note: The article linked here about content moderation is disturbing, but worth a read.) And of course, the whole affair is just a terrible game of whack-a-mole, with moderators deleting one offensive post only for it, or something worse, to reappear elsewhere, perhaps only seconds later.

Across the board, from platform owners to content creators, social media’s primary appeal lies in its scale. Platforms like Facebook boast billions of users, but controlling such vast populations is practically impossible. Instead, the algorithms that drive these platforms amplify sensational content, too often rewarding misinformation and outrage. This cycle of unchecked “megascale engagement” exacerbates the spread of harmful ideas, violent rhetoric, and offensive imagery.

Adrienne LaFrance, a journalist, describes this phenomenon as social media’s “unprecedented user base”—a scale that platforms exploit for immense profit while disclaiming responsibility for the chaos it creates. As media scholar Siva Vaidhyanathan points out, the problem with Facebook isn’t just its misuse; it’s the platform itself.

Efforts to moderate content, whether through human oversight or artificial intelligence, have proven inadequate. Regulators and tech companies propose solutions, but these fail to address the core issue: the unfettered scale of online communication.

IMPOSING CONSTRAINTS

One solution may be to limit social media activity. History shows that such constraints can shape behaviour. For instance, early Twitter capped posts at 140 characters, while YouTube once restricted most videos to 10 minutes. These limits fostered creativity within boundaries.

Imagine applying similar constraints to reach and frequency. Posts could be capped at one per day or restricted to smaller audiences. Content might expire after a set time, mimicking Snapchat’s ephemeral model. Such measures wouldn’t eradicate harmful behaviour but would likely curb its spread.

Some platforms already incorporate limitations. LinkedIn, for example, stops counting connections after 500, encouraging users to focus on quality. Nextdoor confines interactions to verified neighbourhoods. While not foolproof, these restrictions aim to create smaller, more manageable communities.

Google+ offered a blueprint for constrained online interaction. Launched in 2010, the platform allowed users to categorize connections into “circles,” acknowledging the nuances of relationships. This design encouraged people to distinguish between close friends, colleagues, and acquaintances.

Sociologist Mark Granovetter’s research underpinned this approach. He argued that strong ties—relationships built over time—are more reliable and trusted than weak ties, which dominate online spaces. Weak ties can provide new opportunities but are inherently less trustworthy. Google+ attempted to balance these dynamics, but its failure to gain traction led to its shutdown in 2019.

A PATH FORWARD

Beyond the usual strident critics, many everyday users are coming around to the thinking that the current state of social media demands intervention. Regulatory efforts, like breaking up tech monopolies, may address corporate power but won’t resolve issues of scale. Instead, meaningful constraints on user activity could redefine online interactions, prioritizing quality over quantity. However, since many tech giants are based on the premise of data harvesting (which finds more value in scale), even measures like this would likely be implemented only if mandated by government regulators. Leaving it to the platforms to self-police would almost certainly be a failed exercise.

That said, though, imposing such limits aligns with the creative ethos of technology, if not necessarily with their financial goals. If we accept word limits for tweets or time constraints for videos, why not restrict audience size or content longevity? These measures could reduce the relentless flood of content and foster healthier, more meaningful connections.

Ultimately, the internet—or more specifically, social media—needs recalibration. By rethinking its scale and scope, we might reclaim its potential as a tool for genuine communication… even if we never again get that magic number down to just 150.

Information from The Atlantic, The New York Times, Wikipedia, Vox Media, and The Verge contributed to this article.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "