Manglish, Malaysia’s unique fusion of languages, is more than just quirky grammar and slang. This fascinating blend reflects the country’s rich multicultural identity, and for expats, learning even a little can be a game-changer in fostering deeper connections and understanding.

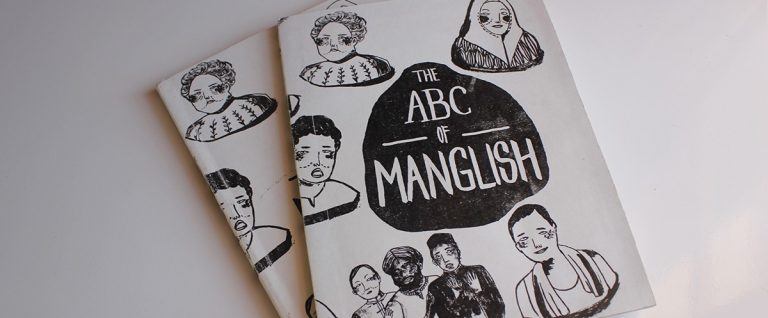

Do you speak Manglish?

Even if you’ve never heard this word before, chances are you’re been exposed to it on a daily basis. A portmanteau of ‘Malaysian’ and ‘English,’ Manglish can be heard in the odd grammar of phrases such as how many you want or where got? or its famously cryptic series of lahs and mahs slapped to the end of sentences. (The Singaporean variant of this phenomenon is, of course, known as ‘Singlish.’)

To both locals and foreigners alike, Manglish is a fascinating subject of how much the English language can be terraformed to fit our multicultural landscape. While the Americans and British wring hands over color vs colour, Malaysians are haphazardly lumping up to four languages into one sentence. But beneath its linguistic quirks, Manglish has a unique history and identity that can say a lot of an expat’s fluency and assimilation and, if learned, have impacts on major aspects of living life here, from the friends they make to how successful they are in business.

HOW WAS MANGLISH BORN?

It’s important to note that the birth and evolution of languages are highly sensitive to sociopolitical and cultural shifts in a society. To put simply, Manglish emerged in the 20th century as a result of British colonialism and our country’s multiethnic demographic. British Malaya lasted for roughly a century, beginning in the 18th century and officially ending in 1957, but a hundred years was more than enough time for them to import their culture and language. Local Malayan leaders were forced to learn their colonisers’ language for administrative affairs, and soon it had to be taught to laymen. With that, the British made English the language of governance and instruction in schools.

This should’ve been the death of Malaya’s local tongues, namely Malay, Chinese, and Tamil. Languages die out when native speakers begin interacting with other speakers of a more ‘elite’ language and lose their need to maintain proficiency in the other. This was certainly the case for urban groups in Malaya, where most were inclined to make English their primary language so they could obtain better job opportunities working for the British. However, the gamechanger was vernacular schools, which conducted studies in the students’ mother tongue, while teaching English as a separate subject.

The introduction of vernacular schools allowed Malayans to preserve their native languages, but this made English the lingua franca for anyone needing to communicate outside their racial group. As such, the English spoken on the streets evolved to use a mixture of characteristics brought over from its speakers’ first language. Even after independence, this variant of English remained to be important despite Malay being officialised as the national language.

FEATURES OF MANGLISH

Though most native English speakers (and other English-speaking foreigners) can understand Manglish fairly well, it is in fact highly dependent on the speaker’s social class or group. As a melting pot of other languages, there is no set limit to how many words or phrases can be thrown into the mix. Some may use more Malay than English, and some speak complete English, relying instead on archaic words or direct translations (for example, ‘close the light’ to mean switch off the lights because the Chinese word for it literally means close, like ‘close the door’).

Manglish’s dependence on multilingualism means having lots of overlaps and intersections in the semantic world. Those famous suffixes—the lahs, mahs, lehs, etc.—are borrowed from Mandarin to change the meaning of whole sentences, with lah adding casualness (or ‘softening’ the tone) and meh being the equivalent to is that true? Its tonal feature has also been adapted, with both the suffixes and English words obtaining an expanded range of connotations just based on the inflection with which it’s spoken.

I like to think that it is due to this ballooning of meanings that Manglish has an offensively carefree grammar. Sure, it sounds terribly unrhythmic, but some have come to view it as a more efficient way of speaking. Instead of saying “I’m going to play games,” Manglish speakers will cut out anything non-essential: “I go play game.” Another favourite Manglish sentence of mine: “Can then can, cannot also can.” Translation: If you’re able to, that would be great, but if you can’t, that’s fine, too.

MANGLISH TO GET AROUND

Similar to how outward appearances influence your interactions with people, your language or dialect leads to inferences about your background – your culture, socioeconomic status, sexuality, and so on. It may even carry more power than your looks since how you speak is more reflective of your values and beliefs. And so, if you spoke the same way as a stranger, wouldn’t it be easy for them to believe you think like them?

This is why knowing Manglish can be advantageous. It is an indicator of commonality. Manglish isn’t something you can just pick up in a classroom; you likely would’ve had to spend a lot of time with locals and live a mostly Malaysian lifestyle. That is the easiest way to learn a nuanced language like that – it’s through exposure to other speakers. And this can be more natural than you think. Some migrants feel obligated to alter the way they speak in a foreign environment, especially if they’re the minority. It’s not necessarily a conscious feeling.

As humans, we’re simply hardwired to adapt to new places and pursue belongingness with other people. It’s why your friends go on holiday to Europe for a few weeks and return with a new accent or unfamiliar slang.

But unlike sporting a French accent after a recent trip to Paris, Manglish grapples with the elitism of its English roots and the street talk of common folk, such that for years now many debate the appropriateness of its use. In the workplace, some deem it as too ‘incorrect’ and informal to be professional. But they forget Manglish is such a culturally rich product of history and national identity that it just naturally invites familiarity between speakers. Many employees continue to use it anyway, simply because it builds rapport and makes working with one another more authentic.

Understandably, from an expat’s position, it’s not easy to learn. But even just understanding Manglish, at the least, can make a big difference in catching the subtle meanings not provided for by English, especially within those tonal words and suffixes. It’s often a pleasant surprise when we hear a foreigner catch on to our Manglish because it shows their effort to assimilate. In other words, Manglish fluency is an easy tester of a person’s ‘Malaysian-ness,’

And that’s just what it is: an easy tester. What does it mean if you haven’t gotten Manglish – let alone a Malaysian accent – perfected? Certainly not that you don’t belong. Again, language is much like physical appearances – surface-level and having a lot of stereotypes working for it in the background. And it’s good to be reminded it’s a two-way effort. As much as one tries to accommodate another, oftentimes the other is doing the same. So many times, I’ve seen Malaysians automatically lighten their Manglish and even switch accents when speaking to expats. I think that they, too, just want to make you feel at home.