Apart from water, tea is the most widely consumed beverage in the world, and with a history dating back over 4,500 years, it’s safe to say it’s been around awhile, too. Editor Chad Merchant takes a closer look at the fascinating world of tea and learns more about teas in Malaysia, too.

It’s more popular than soda, coffee, and all manner of alcoholic beverages – combined. It confers numerous health benefits, is widely available pretty much everywhere, and has virtually no calories. Entire rituals have been built around its serving, and at least one minor revolution supposedly centred around it. Of course it’s tea we’re talking about! With all the attention paid to the vast constellation of cuisines available in Malaysia, it’s easy to overlook the fact that the country is a great confluence of tea culture, too. Drawing in equal measure from the tea heritage of China, India, and of course, merry old England, Malaysia is as good a place as any for a spot of tea.

Here’s what you need to know to be an informed connoisseur.

The basics

Just as all true wine starts with the grape, all true tea starts with the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant, an evergreen shrub that’s native to Asia. (True teas must involve the tea plant. Though the term ‘tea’ is colloquially used for other beverages, such as herbal teas, these are in fact not true teas. Increasingly, the word tisane is used to describe infusions made from non-tea sources.) The Chinese first developed tea as a medicinal drink, and in time, it grew popular as a recreational drink, and became increasingly commercialised in China and surrounding countries in Asia. Centuries later, Portuguese priests returning from Asia introduced tea to Europeans in the 1500s, and within just a few decades, drinking tea became popular in Great Britain. The Brits promptly proceeded to implement and ramp up the cultivation and production of tea in their colonies in India, chiefly in order to get around China’s relative monopoly, and before long, tea became inextricably linked to English life.

At its most basic, there are four types of tea: white, green, oolong, and black. These designations refer primarily to the amount of oxidation and wilting the leaves are allowed to undergo. Green and white teas are the least oxidized, as you might suspect, with the oxidation process arrested by a number of methods to preserve the fresh, vegetal characteristics of the leaves. The only difference is that white tea allows the leaves to wilt, while green tea requires unwilted leaves.

Oolong tea is semi-oxidized, with the process stopped midway and the leaves bruised. Many popular teas fall into both of these categories with Japanese Sencha being an example of the former, and Chinese Tikuanyin the latter. Finally, there is the world of black teas, like Assam and Darjeeling, which are fully oxidized and, in some cases, like pu-erh, further aged after this, a process that can even involve microbial fermentation. More on pu-erh later, as it’s in some ways truly in a class by itself.

That tea costs how much?!

Even non-connoisseurs know that rare, vintage wines can cost a small fortune. There are teas that follow a very similar formula, too. The rarer the tea, or more specific the place of cultivation, and the older the tea, the pricier it can be. Singapore-based TWG Tea, for example, has a Chinese loose tea called Yellow Gold Tea Buds that cost a whopping S$528 for a scant 50 grams. That’s RM1,668 at current exchange rates, so each cuppa (using 2.5 grams of tea) will set you back over RM83.

Why so pricey? For this tea, it’s not about the age, it’s about the relative rarity. First, the tea leaves are cultivated from a single mountain in China, and the harvest is only carried out one day of the year. The leaves – just buds, really – are taken from only the topmost part of the tea plants, and after curing, each tea bud is painted with a thin layer of edible 24K gold.

Certain varieties of Japanese Sencha is also quite expensive, and if you want to see some costly teas from the Empire of the Rising Sun (as well as some more moderately priced ones), you need only pay a visit to ISETAN The Japan Store in Lot 10. Head downstairs to the Market floor… and get your wallet ready!

China’s favourite green tea, longjing, can soar into truly crazy prices for the most prized varieties, the king of which surely must be Dragon Well, with people paying hundreds of dollars for just a few grams.

But the coveted Da Hong Pao tea might just hold the crown for price. This tea is legendary in China, and the original version isn’t content to be merely worth its weight in gold: it’s actually about 30 times costlier!

A single gram costs some RM6,200, so just a cup of this tea would hit your wallet to the tune of RM15,000, while a pot would be an indulgence fit for an Emperor, setting the purchaser back over RM44,000, easily eclipsing the price tag of several models of local cars in Malaysia!

Why is Malaysia a good place for tea drinkers?

It’s not so much because tea is grown in the highlands of Malaysia (though that certainly helps), but more so because the country represents an organic confluence of the world’s most celebrated tea cultures – China, India, and the UK.

Here are just some starter notes on a sampling of the many types of tea you can find on offer in places around Malaysia:

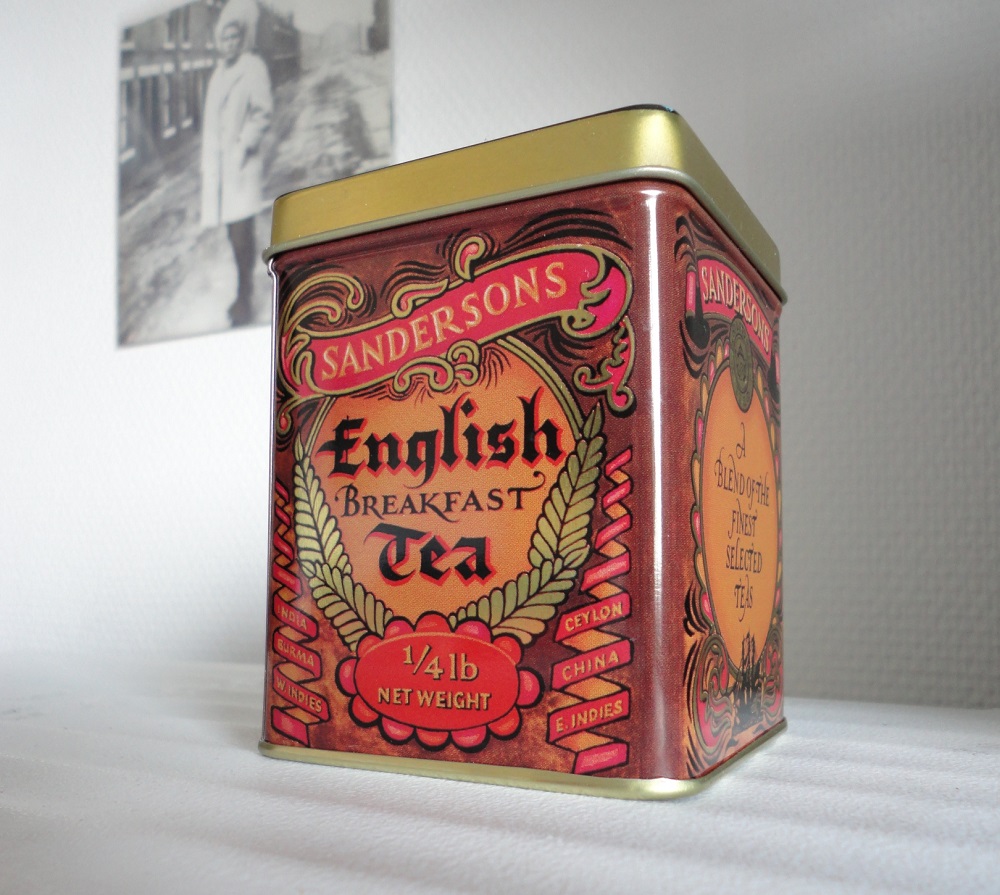

English Breakfast Tea

You would think the name tells you virtually all you need to know about this popular tea. But curiously, the tea is a blend of black teas typically from Assam, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and Kenya. And though the practice of drinking a blend of black teas for breakfast was popularised in the UK, even the common name we know isn’t ascribed to the English: there, it was always likely known as simply ‘breakfast tea.’ The addition of ‘English’ to the title is thought to have originated in the United States in around the mid-19th century.

Earl Grey

Thought to have been named after Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, and British Prime Minister in the 1830s, this tea is typically a blend flavoured with bergamot oil, an essential oil from the bergamot orange fruit. It is believed that the Earl received a diplomatic gift of this tea blend, and it soon came to bear his name. Originally made with black tea, manufacturers have in recent years begun to deviate, trying variations with white, green, and oolong teas, and adding other ingredients in addition to the bergamot oil.

Earl Grey tea was given plenty of exposure during the run of Star Trek: The Next Generation, as it was the drink of choice for Captain Jean-Luc Picard, who would always order the beverage from the ship’s replicator with the command, “Tea, Earl Grey, hot.” Netizens offered various theories on the odd syntax, with one assuming the computer might have produced the actual Earl, steeped in hot water, had Picard ordered, “Hot Earl Grey tea.”

Darjeeling

Though most commonly produced as a black tea, this tea from the Darjeeling district of West Bengal, India, is also produced in white, green, and oolong variants. With a fruity and floral fragrance, this tea is thin-bodied, but nonetheless assertive and has been called ‘The Champagne of Teas.’ Unlike many Indian teas, which are made from the large-leaf Camellia sinensis assamica plant, Darjeeling is made from the small-leaf C. sinensis plant.

Chamomile

The sole ‘not really a tea’ tea on our list, chamomile is a popular beverage made from an infusion of a flower that looks similar to a daisy. Chamomile is an herbal infusion typically consumed to treat a number of minor maladies, such as hay fever, general inflammation, insomnia, ulcers, and menstrual pain. It is also believed to be a digestive relaxant. Though a number of chamomile species can be used for the infusion, the two most common are German chamomile (Matricaria chamomillia) and Roman (or English) chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile).

As there are numerous chemical compounds in chamomile – and all the associated pharmacology and drug interaction risks – sensitive individuals should check it out before consuming. (For example, pregnant women are advised not to drink Roman chamomile as it can cause uterine contractions that may lead to miscarriage.)

Green Tea

Green tea is made from leaves which have not been allowed to wilt or oxidise and has enjoyed a surge in popularity in the last couple of decades, largely owing to its purported health benefits. Many of these benefits claims have no conclusive scientific support, though bodies of anecdotal evidence do seem to suggest that at least some of them are true, including the association of daily consumption of green tea with lower blood pressure and lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease. Green tea is widely available from many producers, in a comprehensive range of qualities and prices.

Assam

Hailing from the world’s largest tea-growing region – Assam, India – this black tea yields a strong, brisk, full-flavoured cuppa. Sweltering tropical heat and prodigious rains during the monsoon create a greenhouse-like climate that contributes to the unique flavour of Assam tea leaves, a brisk, malty character that really sets this tea apart. This climate also allows the leaves of the Camellia sinensis assamica plant, a variety distinct from the Chinese plant (though the same species) to grow considerably larger. Indeed, Assam and Southern China are the only two areas in the world with genuinely native tea plants.

And if you’re ever enjoying Assam tea, you can wow your friends with this bit of tea trivia: the tea gardens in Assam do not follow the same time zone as the rest of India. To increase the productivity of tea garden workers, the area follows ‘Tea Garden Time,’ which is one hour ahead of Indian Standard Time!

Tieguanyin/Tikuanyin

You’ll no doubt see this one spelled any number of ways, as the word as written is merely a transliteration of the Chinese characters (铁观音) for this favoured premium oolong tea, often shortened to ‘TGY’. Named after the Chinese Goddess of Mercy, Guanyin, the tea originated in China’s Fujian province in the 19th century, making it a relative youngster on the Chinese tea scene. The cultivation and processing of tieguanyin is of paramount importance in highlighting the tea’s best character, so makers tend to jealously guard their secrets of its processing.

TGY tea is oftentimes categorised by the season of its harvest, or alternately, by the level of its roasting during processing. A blend of Jade TGY (lightly roasted) and Autumn TGY (strongest aroma) is considered a very desirable blend, with the Spring TGY generally regarded as having the best overall quality.

Lapsang Souchong

You’ll be a true tea smarty-pants at the table if you order this lesser-known (but increasingly popular) Chinese tea, which has its origins in the Wuyi region of the Fujian province. A black tea, lapsang souchong is distinctive because the lapsang leaves are dried with smoke from pinewood fires, giving the beverage a uniquely smoky note. (The word souchong, meanwhile, refers to the fourth and fifth leaves of the tea plant. These are less desirable than the prized buds at the top of the plant, so it’s thought that drying the leaves over smoke would provide a marketing hook for these particular leaves.)

Though referred to in China as ‘tea for Westerners’ – as it enjoys a good reputation outside China – lapsang souchong can nevertheless seem to evoke durian-like reactions in consumers: you either love it or hate it.

Pu-erh

Entire essays (and indeed books) have been written on this celebrated tea, one which is rather unique in the pantheon of Chinese teas in that it has a protected, designated origin by law (though, of course, abundant knock-offs still exist). Pu-erh refers to a variety of fermented and post-fermented teas which are grown in the Yunnan province of China.

Further, all pu-erh tea is made from máocha, a mostly green (unoxidized) tea processed from the large leaves of the Camellia sinensis assamica plant. At the máocha stage, oxidation has been stopped. From there, however, the tea can be packaged and sold, or shaped into cakes or bricks and allowed to age and ferment. There are, accordingly, four main types of pu-erh which are commonly available:

- Máocha: Green pu-erh leaves sold in their loose form as the raw source for making pressed pu-erh.

- Green (raw) pu-erh: Pressed máocha which has not been subjected to any other processing; high-quality green pu-erh is highly sought by aficionados.

- Ripened pu-erh: Pressed máocha which has undergone an intensified, accelerated fermentation process (45-60 days). Any flaws in this process can result in a very bad tea.

- Aged raw pu-erh: Pressed máocha which has undergone a slow secondary oxidation process, followed by microbial fermentation. The most highly regarded of pu-erh

Processed pu-erh tea is sorted into at least 10 grades, based on metrics such as leaf size and quality, and then further categorised by harvest season. It’s a pretty complex system, and it underscores the near-fanatical reverence connoisseurs of Chinese tea have for this tea. So prized is pu-erh, in fact, the best known areas for growing the tea plants are referred to as the Six Great Tea Mountains of China, a group of mountains in Xishuangbanna renowned for their unique tea-growing characteristics, much as the famed banks of the Gironde River in Bordeaux are known for yielding superlative wine grapes.

Special mention: Teh Tarik

So there you have it – a primer on tea to help you enjoy your next afternoon cuppa just a little more. Of course, no article about tea in Malaysia would be complete without a mention of the country’s own famous contribution, teh tarik.

Translated as ‘pulled tea,’ this popular local beverage comprises brewed black tea, usually not a particularly fine grade, and sweetened condensed milk (or in some cases, evaporated milk). The tea and milk blend is then poured back and forth between two containers, often at considerable distance, which represents the ‘pulling’ – this action mixes the ingredients, cools the beverage slightly, and puts a nice frothy head of foam on top.

Considered to be Malaysia’s national beverage, teh tarik is an inextricable part of the country’s food and beverage heritage, and just one more reason why Malaysia is a great place to be a tea aficionado!

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "