Fake news. It’s a phrase that really didn’t gain serious traction until recently. Despite certain politicians using the term to reference an unflattering report or any news they don’t personally like, ‘fake news’ actually refers to phony or inaccurate ‘news’ articles that are purposefully placed to confuse, deceive, or just create a fog of misleading information. Today’s digital era facilitates this with shocking ease, and the consequences of intentional, coordinated ‘fake news’ campaigns can be dire.

However, lately it’s become clear to me that what’s also pretty fake these days is what’s being peddled by this new breed of would-be advertisers: the so-called ‘social media influencers’. What began as PR agencies tying up with bloggers and even sending them a few free samples in hopes of some positive word-of-mouth has mushroomed into an industry now valued at over a billion dollars. Now these same PR people are handing over thousands of dollars (in addition to free products and travel) in exchange for a pretty picture and a few hashtags.

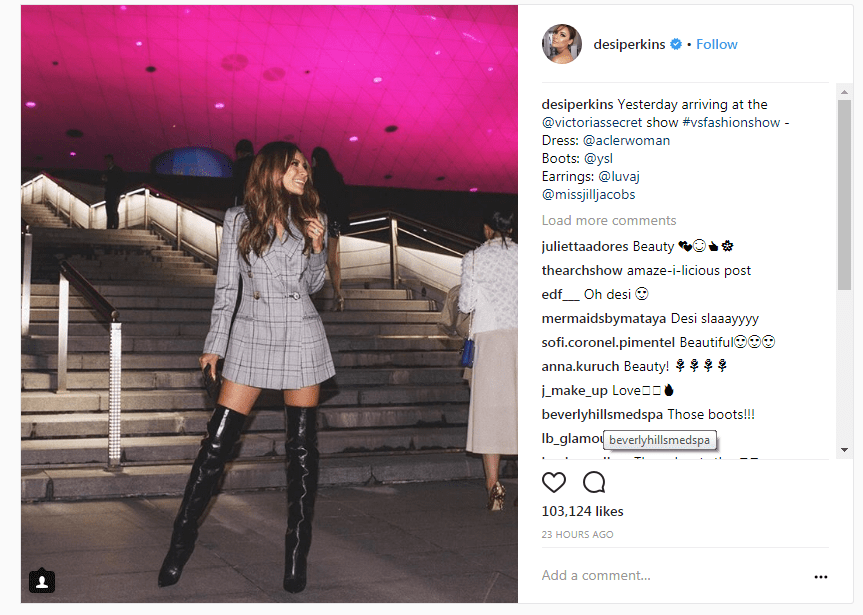

On the surface, it might make sense. A brand engages with a self-styled ‘influencer’ who has tens (or hundreds) of thousands of followers on social media – Instagram is probably the most popular platform, but Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are all heavily used, too – with the idea that a shot of their product or service will translate into engagement or, ideally, sales. It didn’t take me long on Instagram to see just how prevalent this is – and how potentially devious. You start following someone because you like their posts. Over time, they build up a huge following. Sometimes this happens organically, but there are far less scrupulous ways to amass thousands of Instagram followers, too, seemingly overnight.

Too often, these so-called followers are not even real people, but merely bots, purchased in bulk in a bid to drive up the number of followers. In fact, photos and reports freely circulate of actual vending machines in Russia where you can buy followers and likes on social media!

There are admittedly some pros (and plenty of obvious cons) to buying ‘followers’ in bulk. But as long as the numbers are there, once this person has so many followers – real or not – it’s not that hard to monetize it because marketers are lining up to throw money at these self-styled ‘social influencers’. And lest you think it’s just a fad, consider that in 2016, over US$23 billion was spent on social media marketing, a figure that doesn’t even fully take into account the estimated $1 billion-plus paid to private influencers (as opposed to being paid directly to the platforms themselves). And in 2017, there’s been only more growth, with no signs of it stopping any time soon.

Show me the money

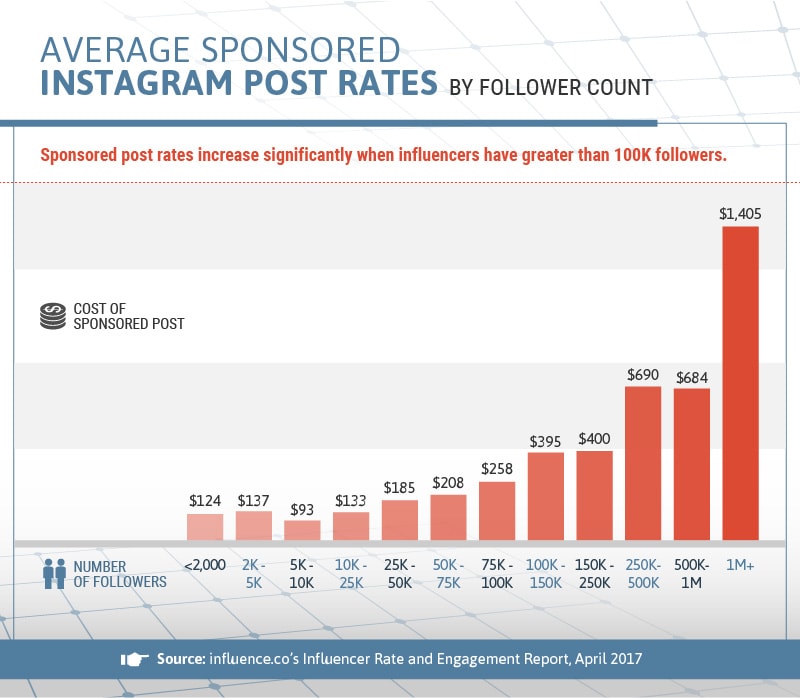

How lucrative can it be? One jet-setting couple in the United States with over a million Instagram followers won’t even bother for anything less than US$3,000, a fee that’s paid on top of all the expenses being covered for the vacation that they’re posting about. In Singapore, one influencer with over 300,000 followers charges S$1,800 per Instagram post. Another, with around 20,000 followers, gets a more sedate S$500 per post, but S$2,000 for a YouTube feature. Anything over 100,000 followers seems to be the magic number; that’s the level where the coin can start really adding up. Currently, the average cost for a post by someone with that many followers is about US$600.

It would be easy to write this off as mere jealousy on the part of naysayers, but what really frustrates me is how some influencers – especially the fake ones – are taking advantage of that precious, short time between an industry’s emergence and its maturity. These marketing people who are forking over such large sums of money at Instagrammers and YouTubers are just stumbling around in that ill-defined gray area when the metrics for this industry are still being determined. And when even Facebook estimates that up to 11% of its users are fake, it makes defining the parameters for the market all the more challenging.

Beyond that, even if the followers are real, how deep does the actual influence really go?

Consider: If you have Instagram and follow dozens (or hundreds) of feeds, unless you’re checking your own feed every few minutes, you’ll likely not see anywhere close to all of the new posts added since your last check-in. There are just too many, and few of us have time to scroll, scroll, scroll for so long to see every post. And when you are scrolling, how often do you stop on a post, look at it closely, and read the accompanying text? That’s what I would call ‘engagement,’ but really, merely double-clicking on an image (indicating a ‘like’) counts as a reader engagement in the biz, whether or not you have any clue of what you just clicked on as you rapidly scrolled by.

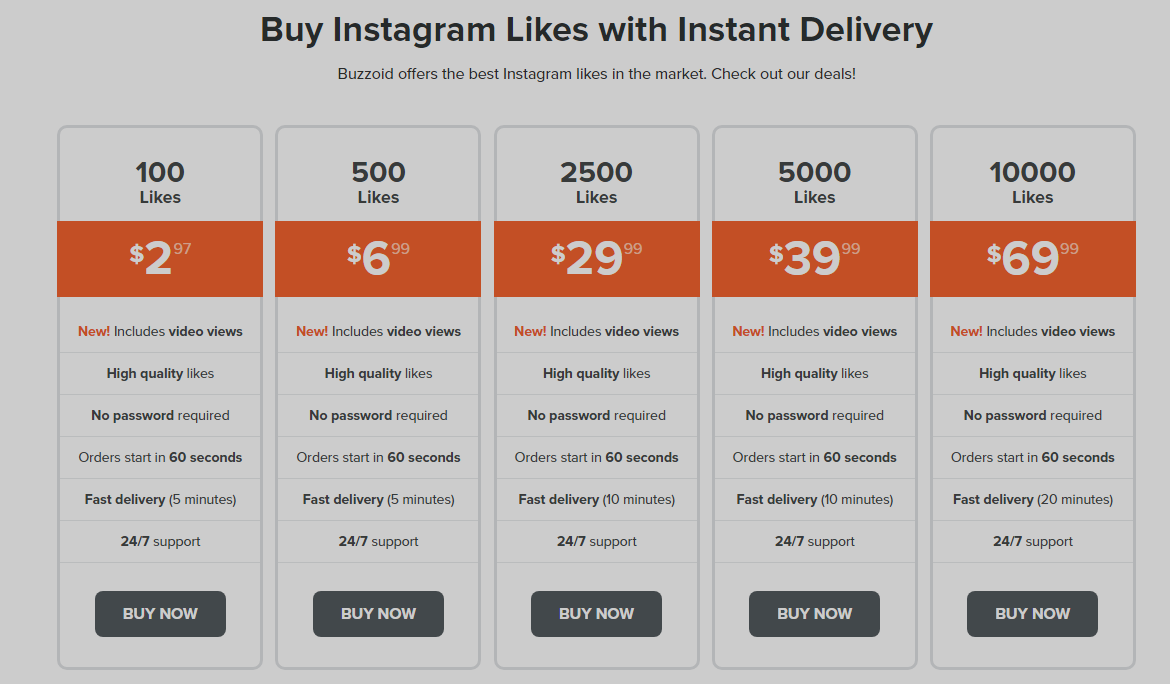

So if the influencer posts a picture and gets, say, 900 likes from her 200,000 followers, what does that really mean? How do you quantify that or presume to call that ‘engagement’? How many of those 900 people would even remember what they double-clicked on as they scrolled through their feed? Who’s really being influenced? (And more to the point, I understand you can even buy ‘likes’ just like you can buy large masses of followers.)

Additionally, millennials and Gen Z social media users strongly report being able to tell when a post is based on an ad contract, and are usually turned off by it, so it’s important to brands to promote their products and services in an authentic manner, and if not, to at least be transparent – we’re seeing more and more posts tagged now with hashtags clearly identifying them as sponsored.

All that having been said, the recent growth of this industry has nevertheless been meteoric, particularly with Instagram. From 2014-2017, Facebook has grown by 57%, and YouTube by 50%. Instagram, meanwhile (which is now owned by Facebook), has charted a staggering 357% growth in that same period. Instagram also nets advertisers the most results, by far, with 72% of Instagram users reporting they made a buying decision based on something they saw on the site.

Overall, 75% of consumers report relying to some degree on social media to inform their purchasing decisions, so it’s little wonder that advertisers are flocking to these platforms in droves, with ‘influencers’ both real and fake predictably lining up to accept their cash. For the rest of us, the challenge becomes separating what’s real and genuinely recommended from what’s simply been bought and paid for. The difference between this new frontier and more traditional advertising, like print ads and billboards, is pretty easy to define. As one person put it (and I’m paraphrasing here), “When you look at a traditional ad, you know you’re being advertised to. You can put up your defenses on some level, simply because you know they’re trying to sell you something. It’s honest and it’s clear. With social media, it’s less much less so. Is it a friend giving you a personal recommendation or is it just a cleverly sponsored post that’s been contractually arranged?”

A rapid evolution

With the fledgling industry featuring a near-total lack of accountability and authenticity, I think it’s just a matter of time before marketing people figure it all out and the ‘influencer’ gravy train, while surely not derailing entirely, at least evolves to something quite different than what it is now. Microinfluencers (5,000 to 25,000 followers), for one example, are gaining steam as advertisers recognise the value of casting a wider net, effectively engaging with dozens of influencers with smaller followings rather than with one celebrity influencer with a huge following (over 7 million) – the top celebrity Instagrammers get up to US$500,000 (and occasionally higher) per post. That kind of money can easily be spread around to dozens, if not hundreds, of microinfluencers. It’s the same total ad spend, but the message gets out to a more demographically diverse audience than it would if it were all placed with just one influencer.

Microinfluencers also drive significantly higher rates of engagement, and most recently, marketers are looking even smaller, to what are called social media advocates (under 5,000 followers), a group that’s been called the next great opportunity, largely because they are far more personally connected to their followers than the mega-influencers and celebrities ever could be, which in turn generates far greater engagement. Indeed, advocates and microinfluencers account for half of all Instagram accounts, and this fact has not been lost on marketers.

Large companies appear to already be catching on and evolving to meet the demands of a rapidly maturing industry. In an interview with Mumbrella Asia, Visa’s head of content, Kris LeBoutellier, said there had been some success in this arena, but that the metrics for predicting and tracking social media marketing results were simply not there yet. “They don’t exist,” he said flatly. “We try to put metrics to stuff.” When asked how you measure success in the social media realm, he replied, “I’ve never met anyone who has given me a solid answer. Once you look at the numbers, and make sure there’s no ‘click farm’ involvement, only then do you know if [a video or campaign went viral or succeeded].” But nobody can say why, nor can it be predicted or planned.

It’s hard to say how this will all shake out, but one thing seems certain: While real influencers (and microinfluencers, which advertisers seem increasingly keen on in the United States) will become a permanent part of the marketing landscape, fake influencers are not engaged in a sustainable business model. We are currently approaching the end of the time when you can just fake your way through it and dazzle people with a cursory knowledge of social media that only barely exceeds that of the average person on the street.

The next generation, the teens and young adults of today, were raised on social media, and they know all the tricks – and, correspondingly, the ways to reliably ferret out hucksters who are just trying to game the system. As the business of social media marketing grows and matures, so too will the methods put in place to detect fakes.

Already, such countermeasures are becoming more and more robust, and the big three social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) periodically engage in mass purges in an effort to rid their system of bots and fake accounts. What’s more, the real value of social media marketing lies in the analytics – the insights and metrics into the presumed engagement the content has with followers such as what they like, what else they follow, when they’re most active, what they are looking for – and if the followers are fake, then these insights are worthless.

Meanwhile, as I push my own little Instagram account along (my next goal: 500 followers), my respect has grown tremendously for people or organisations who have vast numbers of followers, yet don’t turn themselves into advertising hucksters. I follow National Geographic (@natgeo), which is one of the world’s most-followed Instagram accounts with an astonishing 82.5 million followers. And yet there’s no product placement, no ad copy, no exhortations to buy this or that. Just great photos – perhaps the essence of what Instagram was originally meant to be.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "