Judging any government’s handling of an unprecedented public health crisis with major economic, social, and political ramifications isn’t as straightforward as you might think. Here’s our detailed assessment with a full report card for Malaysia’s Covid response.

NOTE: For a shorter synopsis of this article with the grades for each category, please CLICK HERE.

Malaysia is currently in the worst throes yet of a pandemic that has swept the globe and continued for more than a year and a half. How has the country fared? We take a look at the crisis, both through a purely domestic lens and in comparison to regional and global neighbours.

In most countries, it is difficult to separate the challenges posed by the crisis from the political backdrop that influences every decision made in response. Perhaps nowhere is that more true than here in Malaysia. Just as the pandemic was beginning to genuinely make its presence felt in Malaysia, the duly elected Pakatan Harapan (PH) government was effectively overthrown in a series of complex political machinations and a so-called ‘backdoor government‘ – Perikatan Nasional (PN) – subsequently installed.

Since claiming power, the PN government has been largely consumed with handling the coronavirus crisis in Malaysia. How well has this government met the immense challenges posed by what has likely been the country’s broadest and most sustained crisis since Independence?

THE GRADING SCALE & CATEGORIES

Like many of us remember from school, we’re using a five-letter academic grading scale that roughly follows the same ranks, both as standalone and comparative measurements:

- A: Excellent, or far above average

- B: Good, or above average

- C: Mediocre, or average

- D: Poor, or below average

- F: Failure, or far below average

To assess Malaysia’s response, we will look at a number of categories:

- Total Cases

- Total Deaths

- Controlling the Spread of the Virus

- Testing

- Contact Tracing

- Managing the Economic Impact

- Political Concerns

- Social Concerns

- Vaccinations

As these various categories have very different implications and degrees of importance, generating an average overall grade is not possible, so we simply provide specific grades for each category and an overall summary at the end.

TOTAL CASES | CASE RATE

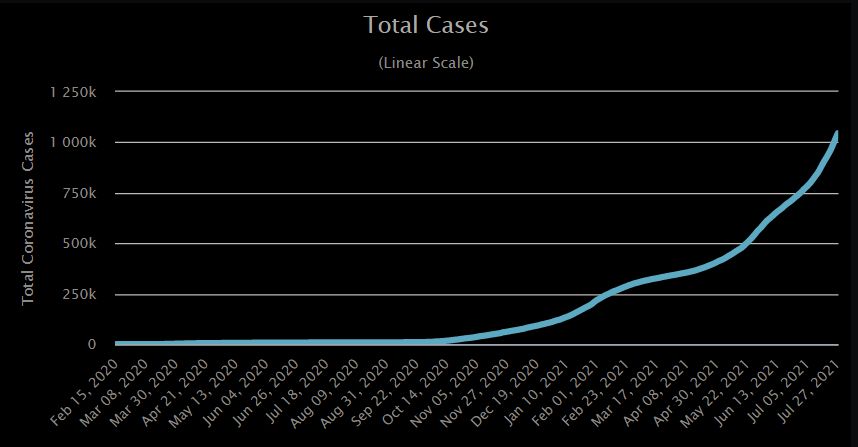

On the first day of Malaysia’s Movement Control Order (MCO) being implemented, March 18, 2020, the country had tallied 790 total cases of Covid-19, a number that, 16 months later as the country is routinely logging over 15,000 new cases a day, seems laughably small.

Barely over 30 countries worldwide have accrued more than 1 million Covid cases during the pandemic to date, but Malaysia is now unfortunately one of them.

While we’re not fans of obsessing over the daily new case count every single day, the total number of cases offers a fair snapshot of how pervasive the pandemic has been in a country, particularly when you look at the cases relative to the country’s population.

Unfortunately, by this metric, Malaysia has failed abysmally, and nearly all of that unravelling has come in just the last few months. As of December 31, 2020, Malaysia had recorded just 113,010 cases. Now, with 1,044,071 cases officially recorded as of July 28, 2021, it’s clear that Malaysia has struggled mightily in the first seven months of 2021.

In fact, when looking at the total cases logged on the first day of each quarter since the pandemic began, you can easily see where the mounting failures really began in earnest:

- April 1, 2020: 2,908 total cases

- July 1, 2020: 8,640 total cases

- October 1, 2020: 11,484 total cases

- January 1, 2021: 115,078 total cases

- April 1, 2021: 346,678 total cases

- July 1, 2021: 758,967 total cases

Factoring in the country’s population of 32.8 million (current estimate), the case rate is 31,823 per one million population (1M), significantly above the world average of 25,142.

Not only is Malaysia the sole ASEAN member to have a case rate above the global average, but its case rate is far higher than any other country in the region. In fact, Malaysia’s rate is more than double that of the number-two ranked country. Malaysia, with the next four ranked regional neighbours:

- Malaysia (31,823 cases per 1M)

- Philippines (14,058 cases per 1M)

- Indonesia (11,713 cases per 1M)

- Singapore (10,925 cases per 1M)

- Thailand (7,764 cases per 1M)

In a global comparison, Malaysia’s case rate is considerably lower than many Western countries, which is perhaps of some dubious comfort, and that’s largely because the spread of the virus didn’t really explode in a big way here until 2021.

Compared to countries with similar populations, Malaysia fares rather poorly, but is certainly not the worst:

- Poland (76,247 cases per 1M)

- Peru (62,948 cases per 1M)

- Malaysia (31,823 cases per 1M)

- Saudi Arabia (14,714 cases per 1M)

- Venezuela (10,615 cases per 1M)

It’s important to note that case detection is directly linked to the rate of testing in a population, so countries which do more testing will naturally pick up more positive cases than those which do not. Details on Malaysia’s testing are included under the ‘Testing and Tracing’ section below.

CASES | Grade: F (regionally); C- (globally)

TOTAL DEATHS | DEATH RATE

Officially reported Covid deaths currently stand at about 4.2 million, with the actual number unquestionably much higher. In absolute numbers, Malaysia’s reported 8,551 deaths is a far cry from the staggering death tolls seen in many other countries, such as the United States (627,351), Brazil (551,906), the United Kingdom (129,303), and Mexico (239,070).

Of the 20 countries with the highest reported death tolls, only four are in Asia: India (442,054), Russia (155,380), Iran (89,479), and Indonesia (86,835). Seven are in the Americas (North and South), and eight are in Europe (Western and Eastern).

Relative to population, Malaysia’s death toll (rate) is also not a global standout: At 256 deaths per 1M, it comes in well below the world average of 537.9 deaths per 1M.

Regionally, however, Malaysia’s death rate is exceeded only by Indonesia’s:

- Indonesia (314 deaths per 1M)

- Malaysia (256 deaths per 1M)

- Philippines (246 deaths per 1M)

- Myanmar (143 deaths per 1M)

Vietnam (5 deaths per 1M) and Singapore (6) have had the best regional performance in this category, though there is a notable difference in the perceived accuracy of the data coming from these two countries. Along those same lines, with just five officially recorded Covid deaths, Laos has only 0.7 deaths per 1M, figures that are frankly impossible to accept as accurate.

DEATHS | Grade: D (regionally); B+ (globally)

CONTROLLING THE CONTAGION

On the first day of the MCO, Malaysia’s seven-day moving average of daily new cases was just 92. As of July 27, 2021, that average stands at 14,881.

The very nature of a pandemic lends itself to an exponential spread of the disease with time. However, how that spread is handled and controlled, particularly in the initial weeks of an outbreak, contributes mightily to a country’s relative success or failure in mitigating the longer-term effects of the pandemic. Actions taken – or not taken – in the beginning of a pandemic can have greatly magnified effects later down the road.

To illustrate this more plainly, consider the early days of the coronavirus crisis in the country. Malaysia’s first case of Covid-19 was recorded on January 25, 2020. It was traced back to three Chinese nationals who had, in their travels, had close contact with an infected person in Singapore. They arrived in Malaysia on January 24, and were treated at Sungai Buloh hospital the following day.

In less than two weeks’ time, the first Malaysian was diagnosed with the disease. On February 4, 2020, a 41-year-old Malaysian man who had recently travelled to Singapore tested positive for Covid-19. Two days later, his sister, who had no travel history to affected areas, also tested positive, and became the first person in Malaysia to contract the virus via local transmission. From that point, the spread was very slow.

Then, an ill-advised four-day mass religious gathering called a tabligh took place at a mosque in Sri Petaling at the end of February and into March 2020. The event, with over 16,000 congregants on hand (1,500 of whom were from outside Malaysia) gave the contagion a massive boost, not only in Malaysia, but in seven other countries, as well, as attendees returned from the tabligh to their home countries. Numerous clusters and thousands of cases spiralled in the following weeks – both in Malaysia and abroad – as a direct result of the Sri Petaling religious gathering.

Faced with withering criticism, PN’s government quickly tried to place the blame on the government they had supplanted (as the initial permits for the gathering were issued during PH’s tenure and before the pandemic began), but Malaysians weren’t having it. There were also efforts to blame solely the foreign tabligh attendees, a claim that was ridiculous on its face given that over 90% of the attendees were locals, but that was just the beginning of Malaysia’s unfortunate pattern of trying to make foreigners the scapegoats for its own pandemic-related failures.

Obviously, going ahead with this mass gathering was incredibly irresponsible on the part of those organising it and displayed questionable judgment by those attending – that part almost goes without saying. But authorities allowing an event of this scale to be held during a known period of a widespread and intensifying viral outbreak was a staggering failure of leadership, and unfortunately still stands as one of the government’s most notable and consequential blunders in the entire pandemic. (They claimed they somehow didn’t even know about the huge four-day gathering until eight days after the fact, which certainly doesn’t get them off the hook by any means.)

From that point, there was no turning back, and additional early mistakes in containment efforts – another religious gathering in Kuching, a large wedding party in Bandar Baru Bangi in Selangor, state-level elections in Sabah – all but sealed Malaysia’s fate.

The four-month surge of cases related to the Sri Petaling tabligh event, however, was but a dim foreshadowing of the explosion of cases to come in 2021. Consider that from the first recorded case of Covid-19 in Malaysia, it took just under a year to reach 100,000 total cases, which occurred on December 24, 2020, with a total count at that point of 100,318. From that point onward, the true nature of a pandemic’s spread can be seen:

- First 100,000 cases: 333 days

- Second 100,000 cases: 36 days

- Third 100,000 cases: 30 days

- Fourth 100,000 cases: 59 days

- Fifth 100,000 cases: 24 days

- Next 500,000 cases: 64 days

Put another way, through the first full year of the pandemic in Malaysia (January 25, 2020 to January 24, 2021), the country recorded 183,801 total cases. In just the 184 days since then, almost exactly half a year, another 860,270 cases have been logged.

It appears likely that the soaring cases in the last few months come at least in part from the emergence of the much more contagious Delta variant, a mutated form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Unfortunately, Malaysia lacks sufficient genome sequencing capacity to track the spread of this variant with dependable accuracy, so the officially submitted count of 78 total cases of the Delta variant in Malaysia as of July 28 is all but certainly a vast undercount.

Regrettably, whenever cases have risen, the go-to response by authorities here has frequently been the imposition of various restrictions and lockdowns, which have shown few, if any, positive long-term results in mitigating the contagion.

Though it’s accurate to say that numerous countries have struggled with Covid’s spread, particularly in 2021, it’s still hard to see Malaysia’s overall performance in this category as a success by any reasonable measure.

CONTROLLING SPREAD | Grade: D

TESTING | CONTACT TRACING

Testing and contact tracing are critical steps in a pandemic, both to effectively gauge the spread and severity of an outbreak, and to mitigate the contagion. But it’s also hard, and owing to that, many countries have faltered on this point, particularly contact tracing.

We would say Malaysia has done reasonably well on both counts. Though there has been great unevenness in the deployment of testing during the pandemic, with the latest ramp-up resulting in a shocking surge of identified cases, the launch of the MySejahtera app in mid-April 2020, with a ‘fully baked’ and stable version released two months later, has been an important tool in the fight against Covid. The smartphone app has become a fixture in the daily lives of many millions of residents in the country, and has enabled and eased contact tracing efforts measurably. The creation and deployment of this app – and its massively widespread use (mandated in all but the most rural of areas in the country) – is something we’d count as a true success for Malaysia.

How consistently and effectively the data generated by the MySejahtera app has been utilised is, perhaps, a topic for debate. However, as far as we can tell, information gleaned from the app seems to have helped in numerous instances, with the app being used to notify users of possible contact with Covid-positive individuals. The data gathered is also used very effectively to communicate hotspots and numbers of Covid cases (over the past 14 days) in a given area, something that’s quite useful for users of the app.

Initially created primarily as a tool to facilitate contact tracing, MySejahtera has evolved to become a near-indispensable ‘superapp’ for Covid statistics, communications, hotspot identification, and vaccination registration and updates.

Testing in Malaysia is distinctly middle-of-the-pack in a global context. Over 17.5 million Covid tests have been performed here during the pandemic, for a rate of about 535,000 tests per 1M population. For comparison, the UK has tested at an impressive rate of 3.5 million tests per 1M, almost seven times the rate in Malaysia. Just over 50 countries worldwide are testing at a rate of more than 1 million tests per 1M population.

Regionally, Singapore naturally leads the pack by a substantial margin, hardly surprising given its size and relatively small population, coupled with how poorly almost all the other countries are doing. Here’s how ASEAN countries shake out, ranked from best to worst by testing rates (per 1M population):

- Singapore (2.67 million)

- Malaysia (534,737)

- Brunei (341,534)

- Philippines (148,039)

- Vietnam (120,989)

- Thailand (116,159)

- Cambodia (101,011)

- Indonesia (91,343)

- Myanmar (56,619)

- Laos (41,284)

Suffice it to say that a direct line of correlation can be drawn between a country’s rate of testing and the accuracy of its reported Covid case numbers.

TEST & TRACE | Grade: C (testing); B+ (tracing)

ECONOMIC FALLOUT

Managing the devastating economic impact of a long-running pandemic has unquestionably been a point of colossal failure for Malaysia. Owing largely to an ill-advised and seemingly scattershot series of lockdowns over the last year and a half, despite plenty of advice (from both health and economic experts) to avoid them, the country has seen at least 150,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) permanently shut down, with the loss of some 1.2 million jobs. The ripple effect has also badly impacted the supply chain for large companies and multinationals, as well.

According to economic data, SMEs employ about half of Malaysia’s entire workforce. In spite of numerous warnings from industry experts, trade groups, and economists, the PN government has consistently used both broad and targeted lockdowns to deal with the pandemic.

In addition to not effectively curbing the spread of the virus, the economic results of these lockdowns and various restrictions have been nothing short of devastating.

The country’s travel and tourism industry has been decimated. Restaurants (and other players in the wider F&B industry as a whole) have struggled immensely. The number of hotels, restaurants, and other businesses linked to hospitality which have closed down in Malaysia is almost beyond belief: More than 120 hotels have shuttered, most for good, with losses mounting to over RM11.3 billion. Untold thousands of eateries and coffee shops have closed permanently, with industry association figures placing the count above 2,000 as of the middle of last year!

For SMEs overall, industry groups have warned that if Malaysia continues with its inadvisable (and largely ineffective) strategy of imposing lockdowns much longer, half of the country’s SMEs – which comprise more than 90% of all companies in Malaysia – could cease operations.

“Far too many businesses are feeling hopeless because they have lost confidence in this government’s ability to come up with sensible and logical policies during this pandemic,” said Opposition Party MP Ong Kian Ming, a former deputy minister of international trade and industry.

SMEs have not received enough assistance, and if the lockdown continues, “many more of them will be shuttered, perhaps permanently,” Ong said.

The lack of a coherent strategy is a fact that hasn’t been lost on multinationals, either, with a number of international chambers of commerce openly voicing concerns about Malaysia’s apparent inability to manage the economic fallout of the pandemic. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has plunged, and investors have been fleeing Malaysia in droves over the past several months, and critics have said the PN government is essentially sticking its head in the sand as a response.

Malaysia’s projected 2021 GDP has been repeatedly revised downward with each passing quarter, with the latest forecast from the World Bank at just 4.5%.

Worth noting is that even a 4.5% rate of growth, which frankly seems optimistic at this point, would only be on an already-battered economy. Malaysia’s GDP contracted 17.1% year-on-year in the second quarter (2Q20) last year – subsequently registering smaller contractions of 2.7% and 3.4% in 3Q20 and 4Q20, respectively – dragging the country’s economy ever downward, to shrink by 5.6% overall for the whole of 2020.

Malaysia registered another contraction (though smaller) of 0.5% in 1Q21, compared with a 3.4% dip in 4Q20, the improvement coming despite the imposition of another MCO in the first quarter of 2021.

However, with the eruption of cases in June and July, particularly in the country’s economic engine of Greater KL, many businesses have not been permitted to resume operations, certainly not at any significant capacity, and it’s unclear when this will happen. Given this uncertainty and the fact that it’s already almost August, we wouldn’t be surprised to see 2021’s projected GDP revised downward yet again – and then possibly still miss the lowered figure.

The only thing sparing Malaysia a failing grade in this category are the economic stimulus measures which, though insufficient to mitigate the immense financial damage suffered by many businesses and everyday people, have of course been better than absolutely nothing. The economic stimulus packages have often been coupled with subsidies or moratoriums on loan repayments.

ECONOMY | Grade: D-

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL EFFECTS

There are very few, if any, countries in which a political element hasn’t been part of the coronavirus pandemic. Politicians are nothing if not opportunistic, and many will use any means to secure an advantage – even if it’s a deadly pandemic.

Surprisingly, with a few notable exceptions, there hasn’t been as much political drama in Malaysia (specific to the Covid-19 crisis) as you might expect. Critics and opposition politicians have certainly been vocal at times, but, to their credit, most remarks have generally seemed to be fairly levelled, rather than being motivated by virtue signalling or political posturing.

For the most part, it’s almost appeared that members of Malaysia’s various political parties have more or less realised that we’re all in this together. Very little is to be gained for the country by political gimmickry during a public health crisis: The coronavirus simply doesn’t care about your race, your religion, or your political affiliation, so all of the usual triggers in Malaysia’s political scene have largely been rendered pointless by this virus.

It’s not to say it’s all been smooth political sailing, though. The proclamation of a state of Emergency in January 2021 – the first in 50 years – was widely and fiercely criticised as unnecessary and little more than a political manoeuvre by Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin as a way to suspend Parliament and cling to power amid deteriorating support. The Emergency was set to run through August 1, and it has been announced that it will not be extended.

More recently, the political shenanigans have included questionable appointments and promotions that critics have contended were carried out solely to shore up support in Parliament, specifically from UMNO members, as the political party’s supreme council publicly withdrew its support for PN and Prime Minister Muhyiddin.

On the social front, the effects of the crisis have definitely been felt more keenly by Malaysians. Depression, suicides, and desperate calls to mental health and suicide prevention hotlines have all increased significantly. Making matters worse, mental health issues are often stigmatised in Malaysia (as in many Asian countries), and suicide is actually criminalised here. The number of suicides has roughly doubled year-on-year in 2021, when comparing the cases so far (468 from January 1 to May 31) to the total number of cases in all of 2020 (631).

The highly publicised “white flag campaign” in Malaysia made international news, and had the double effect of showcasing the kindness and generosity of Malaysians – along with resident expats and refugees – while also highlighting the failure of the government to address poverty and meet the needs of citizens adversely affected by policies enacted as a result of the pandemic.

Just this week, contract doctors in Malaysia staged a walkout in protest of the government’s treatment. Though the primary motivator behind the protest was economic, it’s safe to say the effects of the ongoing pandemic have exacerbated the doctors’ grievances. Threats of police action by officials certainly didn’t help matters, and it was just one more issue adding to the overall stress of the country at large.

The government has also frequently bungled communication and announcements related to the numerous (and sometimes overlapping) iterations of the MCO and associated standard operating procedures (SOPs). Residents and businesses have been repeatedly frustrated by changing guidelines, inconsistent enforcement, and poor communication. Moreover, members of the ‘political elite’ have been busted numerous times on social media flouting regulations, ignoring SOPs or travel bans, and basically operating on a different set of rules to everyone else.

The National Recovery Plan, which was announced to a storm of criticism in mid-June lacks any coherent strategy for achieving the largely arbitrary thresholds set for ‘success’ in each phase. The absence of a clear plan – or even a timeline – for emerging from the pandemic and rebuilding a battered country has led to a pervasive sense of exhaustion and despair.

SOCIOPOLITICAL | Grade: C+ (political); D (social)

VACCINATIONS

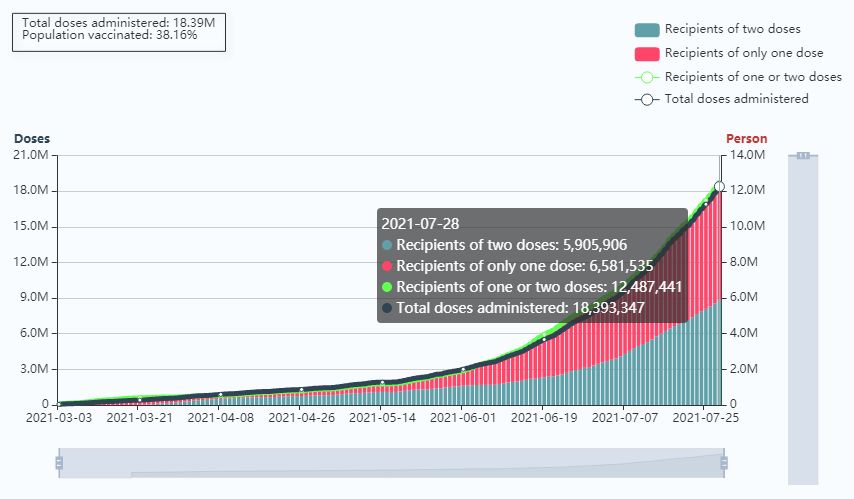

The announcement of Malaysia’s National Covid-19 Immunisation Programme was met with great enthusiasm, as was news of the government’s procurement of ample stocks of vaccines from a number of different suppliers. Subsequently, the arrival of the first batch of vaccines in the country on February 21, 2021 was accompanied by so much fanfare, only a full-scale parade and marching band were missing.

It was a bright moment of much-needed hope for a country wearied by a year-long struggle against a tenacious and insidious enemy. Malaysia further bolstered the good vibes by announcing it would vaccinate everyone in the country – citizens and foreigners alike – at no cost.

The initial swell of joy was, however, not to be long-lived, as the next three months bore little fruit from what had looked like an excellent framework for a mass nationwide vaccination drive. Amid rumours of corrupt practices infiltrating the logistics of vaccine delivery and government-issued statements of delays and difficulties in acquiring the contracted supplies of vaccines, the rollout of Malaysia’s vaccination drive was met with weeks of what appeared to be relative stagnation.

In actual fact, the initial pace wasn’t really that far off from what the plan specified. By the end of April, about 544,000 people had been fully vaccinated, and 1.42 million doses administered overall. That actually fit the plan. By the end of the next month, however, only 508,128 additional people had been vaccinated. This was not a pace that was going to see Phase 2’s goal of 9.4 million fully vaccinated people by August even remotely close to being met, let alone any overlap from Phase 3, also set to begin in May.

But then, almost as if a switch had been flipped, things took off in June and accelerated even more in July. Within weeks, Malaysia’s vaccination rate soared and became one of the world’s highest. On July 27, a stunning 553,871 doses were administered, and Malaysia has now fully vaccinated (both doses) just over 5.9 million residents.

Though there have been some high-profile stumbles involving empty syringes and improperly administered vaccines, these cases are very much the exception to what has become an effective, efficient, and laudable mass vaccination effort. Overwhelmingly, people report a smooth and easy process in getting their vaccine jabs. Science and Technology Minister Khairy Jamaluddin, who heads up the nationwide vaccination effort, has received overall good marks for his ability to accurately communicate vaccination information and updates. Even the official signage and forms are professional in appearance and consistent in graphics, colours, and fonts used, something that may seem unimportant, but actually does wonders to increase confidence in the programme.

Despite the apparent slow start, what has followed is almost certainly the high point of Malaysia’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. The country has now contracted for enough vaccine doses to effectively cover over 130% of Malaysia’s entire population, and the rate at which doses are currently being administered has exceeded almost anyone’s expectations.

Perhaps the only real hiccup now is the inconsistency in vaccination rates from one location to another. For example, Sarawak has administered at least one dose to just under 60% of its population so far, one of the highest rates in Malaysia. Neighbouring Sabah, however, has only achieved 17.9%. Here on the Peninsula, Perlis has seen 41% of its residents get at least their first jab, while not far away, Kelantan is languishing at just half that rate, 20.5%.

Through July 28, about 38.2% of Malaysia’s population have received either one or two doses of the vaccine; the fully vaccinated (two doses) level stands at about 18%. In Greater KL/Klang Valley (Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, and Putrajaya), 61% of residents have received at least one dose.

Given the accelerated pace, Malaysia has brought its goals forward to match, expecting to have enough of the population fully vaccinated to reach herd immunity by the final weeks of 2021. As the vaccines are widely viewed as the only route back to anything resembling normalcy, the importance of Malaysia doing so well on this point cannot be overstated. If you’re going to get anything right in a pandemic, it should be the thing that will put an end to it.

According to Bloomberg’s real-time vaccine tracker, at Malaysia’s current rate of vaccination, it will take about two more months to immunise 75% of the country’s population. (For regional comparison, Singapore should hit this mark in three weeks; Indonesia in 14 months.)

VACCINATIONS | Grade: A-

OVERALL

To be absolutely clear, there is nothing easy about navigating a global pandemic. It puts leaders in the unenviable and often impossible dilemma of having to choose between lives and livelihoods. Those who try to thread the needle in a bid to not pay any price nearly always fail. One way or another, the pandemic will extract its pound of flesh. So any criticism towards government leaders must be viewed through this prism. Dealing with a public health crisis on this scale is incredibly hard. It’s also something Malaysia has never experienced in its short history, having only limited experience with smaller-scale regional outbreaks.

Also worth considering: Far wealthier and more advanced countries than Malaysia failed spectacularly when Covid came calling. The virus is almost perfectly engineered to expose any incompetence in government leadership (see: United States, Brazil, United Kingdom) and to exploit even the tiniest bit of complacency (see: Taiwan, Australia, Japan, South Korea). Even countries that got most everything right, like Singapore, New Zealand, and Hong Kong, have all had serious stumbles that could have conceivably led to things getting quickly out of hand.

There is admittedly at least a small element of luck involved in dealing with a pandemic, but ultimately it takes discipline, tenacity, resolve, and the guidance of intelligent experts in numerous fields – from virology, public health, and epidemiology to finance, macroeconomics, and sociology – to emerge even somewhat unscathed from a global pandemic.

So with that in mind, this report card is not to meant to heap scorn on Malaysia’s government, but hopefully to provide a balanced assessment of the country’s response throughout the first 18 months of an unprecedented global crisis. There have been some successes, such as the terrific mass vaccination effort, and some failures, like an unfortunate reliance on ineffective and economically devastating lockdowns. Overall, however, we feel it’s fair to say there has been considerable room for improvement.

We also applaud the people of Malaysia for their patience, steadfastness, and kindness towards one another. With only a few noteworthy exceptions, the people in this country have shown astonishing goodwill and resilience during a very difficult time and have overwhelmingly banded together to do their part in fighting the pandemic.

The prevailing hope now is that as August arrives, the unnecessary state of Emergency will lapse and fade into memory, the high rate of vaccination will continue, the patchwork quilt of restrictions and bans will stop, and the numbers of severe Covid cases and deaths will drop dramatically as the vaccines’ effectiveness take hold throughout Malaysia.

Stay safe, stay strong, get vaccinated, take care of each other.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "