The contract tracing app has attracted its fair share of controversy from the beginning. New revelations are now threatening to plunge the app and its management into a full-blown scandal.

Is it time to do away with MySejahtera? From nearly all corners – and for very different reasons – the answer “yes” is growing by leaps and bounds.

On one hand, groups (including the Malaysian Medical Association) are raising concerns that the app may have simply outlived its usefulness as Malaysia moves into the endemic phase of the coronavirus pandemic. Nationwide contact tracing efforts are not sustainable given the high staffing costs and broad scope, and that was among the primary uses of the MySejahtera app, which was initially launched on April 16, 2020, less than a month after the first Movement Control Order was implemented.

A much more serious concern, however, lies with the privacy protection of the data collected and stored by MySejahtera. After all, the app records personal details, private health information, and detailed movement records of more than 38 million users.

Many of Malaysia’s residents, both citizens and resident foreigners, have become increasingly concerned about the lack of transparency regarding both MySejahtera’s data protection protocols and even its very ownership. The hashtag #Don’tUseMySejahtera has been trending for days.

It appears to be gaining traction, too. Reports from BFM News indicate that check-ins via the app have plunged by 26% in just four days’ time, from Thursday, when the privacy concern issues were initially raised, to Monday of this week.

Malaysians and resident foreigners who have used the app are growing more and more concerned, and rightfully so: The issues coming to light regarding MySejahtera should be a major red flag for the following reasons:

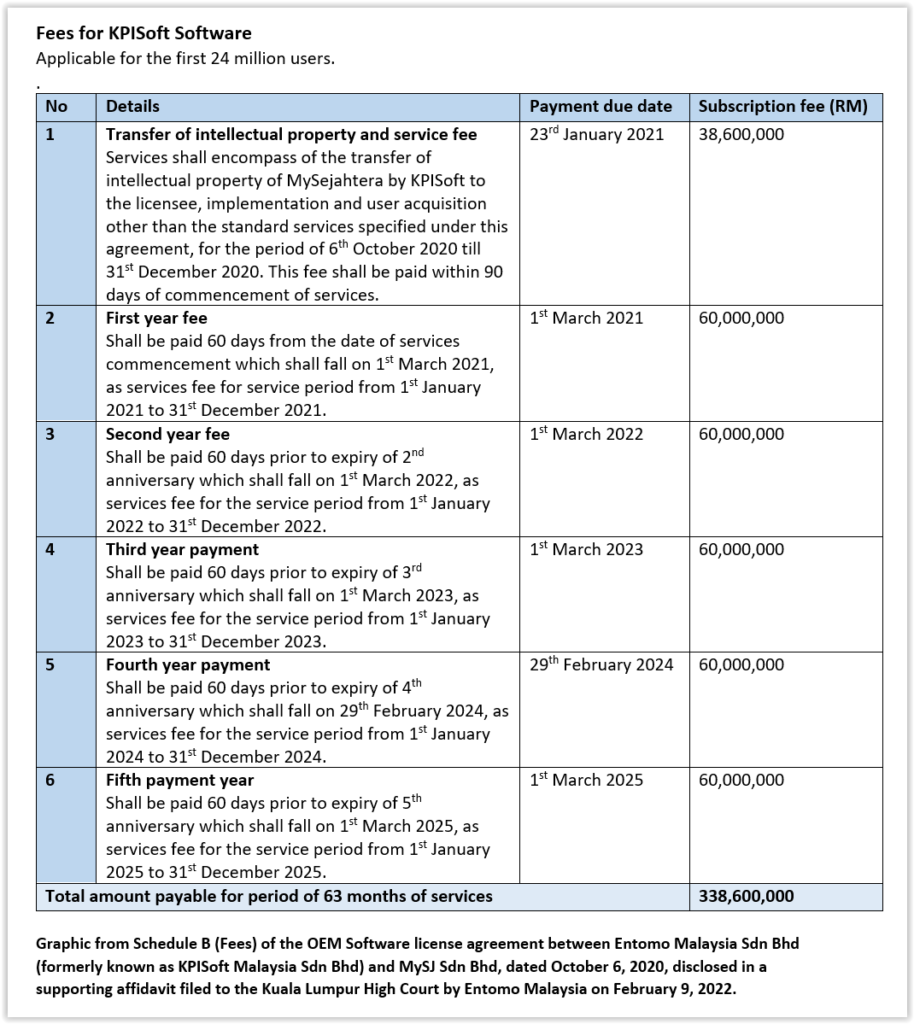

First, the licensing and ownership issues. Court documents that were released as a result of a March 8 query by Malaysia’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC) to the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Health show that the MySejahtera developer, KPISoft, agreed to transfer the Covid-19 app’s intellectual property and software license to MySJ Sdn Bhd for RM338.6 million in a deal until end 2025.

That agreement appears to potentially be in direct conflict with the privacy and data protection policy of the app itself, which plainly states: “No Personal Data collected by this App will be disclosed to any third party or transferred to a place outside of Malaysia for commercial purposes.”

Second, that “outside of Malaysia” part is also problematic. According to the Companies Commission of Malaysia (SSM), the current sole shareholder of Entomo Malaysia Sdn Bhd – which legally owns the software it used to develop Malaysia’s Covid-19 app MySejahtera – is a company registered and based in Singapore, Entomo Pte Ltd.

This doesn’t seem to be a point that’s open for debate, either, as SSM specifically lists Entomo Pte Ltd as a “foreign” company and shows a Singapore address. More on this later.

CONFLICTING ACCOUNTS

Various ministries and key government officials are twisting themselves into knots, occasionally contradicting each other, trying to downplay or explain awaythe swelling concerns.

The above-referenced reports from the PAC hearing, for example, state that Harjeet Singh, Deputy Secretary-General (Finance) of the Health Ministry, told the PAC that app developer KPISoft Sdn Bhd (KPISoft) changed its name to MySJ Sdn Bhd (MySJ).

Concurrently, Rosni Mohd Yusoff, deputy secretary at the Government Procurement Division from the Finance Ministry, has stated that KPISoft and MySJ are two different business entities.

SSM records (and other reports), meanwhile, state that KPISoft Sdn Bhd changed its name to Entomo Malaysia Sdn Bhd in May 2020, while MySJ was incorporated in September of that year.

Finally, according to a comprehensive CodeBlue report, an affidavit filed by Entomo Malaysia (formerly known as KPISoft Malaysia) on February 9, 2021 disclosed the software license agreement dated October 6, 2020 between Entomo Malaysia and MySJ, the licensee – both of which have the same business address at Q Sentral in Kuala Lumpur.

The total fee for this license agreement comes to an eye-popping RM338.6 million, paid over a five-year period. Note that this agreement is expressly between MySJ and Entomo Malaysia, and then recall that they have the same business address.

Confused yet? According to some critics, that may be the entire point, suggesting that a close look at the names and dates involved could potentially suggest some pretty serious shenanigans being orchestrated.

To further add to the kerfuffle, in a press statement dated March 27, the Health Ministry asserted that the Malaysian government fully owns MySejahtera, while mentioning nothing about MySJ.

Oddly, however, Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin stated shortly thereafter that the negotiations with MySJ would not continue should MySJ fail to agree that the government owns the app.

Even on its face, this makes no sense.

How can the government boldly assert that it and it alone owns the app while simultaneously implying that the ownership could be questioned? In other words, why threaten MySJ with the cessation of negotiations if they fail to publicly agree that the government owns the app? Would this fact not be incontrovertible and easily confirmed one way or the other?

It also begs the question that if we conclude that MySJ has not agreed on the apparently inconclusive ownership status of the app, what does that mean for the vast wealth of data the app has gathered and stored for the past two years?

WILL PAST BE PROLOGUE?

Beyond what is happening now and what will unfold in the future, there are disturbing elements from the past, too. Even though the government is telling us that it fully owns the MySejahtera app, the PAC report clearly shows that the app was developed without any contract in place between the government and the app development company, a frankly stunning breach of basic business protocol.

According to Rosni at the Ministry of Finance: “All this time, when the development of the system was being administered by the National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA) or the National Security Council (NSC), there was no proper contract with the [development] company. So, there is no contract.”

This is problematic for a number of reasons ranging from payment to intellectual property ownership to data and privacy matters.

FOREIGN INTERESTS

CodeBlue also reports that despite the NSC stating on July 1, 2020 that KPISoft (which, as you’ll recall, changed its name to Entomo in May 2020) was founded in 2010 by two Malaysians. The NSC also asserted in that July statement that the two Malaysian founders were – and remained to date – the company’s biggest shareholders.

Yet apparently, virtually none of that is fully accurate. SSM records show that KPISoft was actually incorporated on June 21, 2005. Moreover, records show that at least since January 2017, Singapore-based Entomo Pte Ltd has been the sole shareholder of Entomo Malaysia.

The foreign entanglement doesn’t stop there, either. Entomo Pte Ltd’s biggest shareholder is also a Singaporean company. Other shareholders, both corporate and individual, include those in Japan, the United States, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

And that brings us back to the aforementioned “outside of Malaysia” part again, because as a consequence of shareholders’ nationalities, and in direct contravention of the MySejahtera app’s privacy policy, “all rights, title, and interest, including all intellectual property rights” related to the MySejahtera app are, in fact, ultimately owned by a Singaporean company with shareholders in five additional countries, only one of which is Malaysia.

It has understandably caused considerable concern that Malaysia’s National Security Council could seemingly be so easily confused by company registration and ownership matters, let alone the foreign domicile of the sole shareholder, and has fuelled the notion that the personal and medical information of millions of Malaysian residents may be very much at risk.

As reported by The Star when considering the problem of foreign ownership of the MySejahtera app and its components:

“[Malaysians’] sensitive personal data could be at risk of being siphoned out of the country, where Malaysia’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) holds no jurisdiction. How can the government miss this basic due diligence and risk assessment?”

Some additional salient questions posed by The Star include:

- Is Malaysia’s government the sole owner or one of the owners?

- Is Malaysia’s government the only party that has access to the trademark and data collected through the operation of MySejahtera?

- Was the government somehow conned by the owners of KPISoft/Entomo and MySJ?

- We repeatedly see similar names and the same individuals across companies and international borders, engaging in commercial transactions. Is this a case of the “Right pocket dealing with the left pocket, yet somehow, the brain apparently knows nothing about it”?

It’s admittedly an incredibly complex case that will probably see things getting worse before they get better. However, given the enormous sums of money in play for what was meant to be a contact tracing check-in app amid a pandemic, one thing has been made very clear: At least two ministries in the Malaysian government, along with a handful of private companies, have learned what Google and Facebook figured out years ago: In the 21st century, the world’s most valuable commodity isn’t gold or oil. It’s information.

Who has yours?

Documents released by the Public Accounts Committee and reporting from CodeBlue, the editorial arm of the Galen Centre for Health and Human Policy; Tech in Asia; the Malaysianist; The Star; and BFM contributed to this article.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "